Chairman Heinrich, Vice Chair Schweikert, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for inviting me to testify today. My name is Colleen Hroncich. I am a policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom. The views I express in this testimony are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of the Cato Institute.

I will make three main points today:

First, the rhetoric does not match reality when it comes to studies about the effect of early childhood education.

Second, one size does not fit all. Preschoolers and their parents are too diverse for a DC-driven program to make sense.

Third, the FAFSA debacle shows why the federal government should stay away from early childhood education.

Starting with Rhetoric vs Reality

Every few years, there’s a push in Washington, DC for universal or nearly universal preschool. Proponents claim a whole host of benefits, from improved reading ability to fewer dropouts and teen pregnancies to increased future income.

In 2021, President Biden touted such vast benefits from his universal preschool plan that the Annenberg Public Policy Center’s FactCheck.org took him to task, noting, “There is plenty of research on specific targeted programs, but there isn’t much on universal programs. And the research that does exist, in many cases, is more nuanced and less optimistic than Biden suggests.”

There’s no consistent evidence that large-scale preschool programs are beneficial; and there’s evidence they can even be harmful. In January 2022, researchers from Vanderbilt University released a randomized study of Tennessee’s Voluntary Pre‑K initiative that found that children who participated in the program experienced “significantly negative effects” compared with the children who did not. Harms included worse academic performance and higher likelihood to have discipline issues and be referred for special education services. The results were so shocking that the researchers had to “go back and do robustness checks every which way from Sunday,” according to Dale Farran, one of the lead researchers. “At least for poor children,” she concluded, “it turns out that something is not better than nothing.”

Importantly, this program has been deemed “high quality,” being one of few programs to meet at least 9 of the National Institute for Early Education Research’s 10 quality standards benchmarks.i Like similar programs in Boston and Tulsa, teachers must be licensed, are paid at parity with elementary teachers, and receive retirement and health benefits. Classes have a staff member–child ratio of 1 to 10 or better. And instruction is offered for a minimum of 5.5 hours per day, five days a week.

There are several possible reasons for this, but one prominent one seems to be that preschoolers learn best when they have freedom to play independently. Large-scale programs, however, tend toward whole-group instruction, rigid behavioral rules, and too little time outside and in free play.

One size does not fit all The wants and needs of preschoolers and their parents are too diverse for a DC-driven program to make sense. I have four children, and I saw first-hand that different kids have different needs. My oldest daughter was very shy, so my main goal with preschool was to get her comfortable with teachers and other children. I chose a preschool that emphasized play and had a warm, nurturing environment. My second born was not shy, and he was always trying to keep up with his big sister. He was doing 1st grade math and reading small chapter books when he was 4. For him, the challenge of a more academic-based preschool made sense.

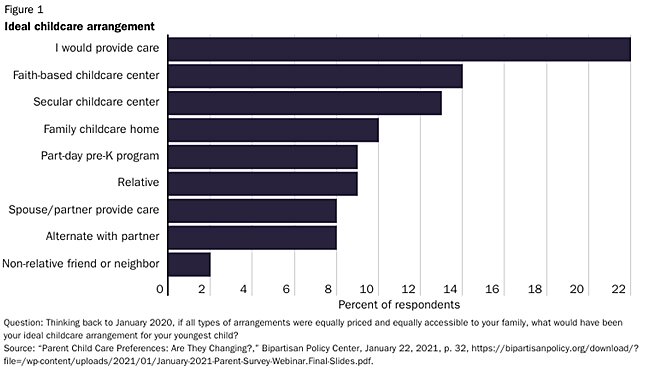

If my own family had diverse needs, it’s not surprising that a December 2020 poll by the Bipartisan Policy Center found parents have a wide variety of preferences when it comes to childcare, including preschool.ii As shown in Figure 1, only 13 percent of parents surveyed chose secular center-based care. About 14 percent preferred a faith-based childcare center. About 10 percent preferred home-based childcare, and another 9 percent preferred a part-time pre‑K program. A federal program would likely have mandates attached to it that would make it very hard for religious and home-based providers to participate. Minimum hour requirements would prevent part-time programs from participating.

Interestingly, 49 percent of parents in the survey said that they would prefer having some combination of themselves, a spouse/partner, a relative, or a friend care for their children. These families would lose out under a federal plan because they would be paying their own way while also subsidizing other parents’ childcare arrangements.

As you’ve probably seen, the nation is undergoing a transformation in K‑12 education, with more and more states taking a student-centered approach instead of the one-size-fits-all model. It would be a terrible irony if preschool education went in the other direction—towards a more institutionalized system—right as K‑12 education is being liberalized.

Finally, the FAFSA debacle should put a nail in the federal preschool coffin.

My youngest daughter is heading to Catholic University of America here in DC for nursing school in the fall. At least, we think she is. We still haven’t heard what our total cost of attendance will be because the federal government has taken a massive role when it comes to college finances. Now most schools use the Free Application for Federal Student Aid—better known as FAFSA—even for private awards. And the Department of Education’s attempt to revise the FAFSA program has been an unmitigated disaster and caused significant delays in the process. This is putting the squeeze on colleges, students, and families—especially lower income families.

There’s a saying, the bigger you are, the harder you fall. When the federal government gets involved, any failures or problems will have widespread impacts. I’m not sure how anyone witnessing the FAFSA mess would think, “let’s get the federal government more involved in early childhood education.”

The Bottom Line

America is too large and diverse for a federal preschool program to make sense. Indeed, the inability to effectively serve specific communities in a sprawling, diverse nation is one reason that the Constitution gives Congress no authority over education at all.

While sound bites and slogans about large-scale preschool may make the idea seem attractive, it is important to look closer and recognize the harms that a federal preschool plan would have on families and providers.

Families have a variety of preferences and needs when it comes to early childhood education. Many families prefer having a parent stay home when their children are young. When a parent is not home with the children, families often prefer home-based, religiously affiliated, or relative care. The rules and restrictions that would be part of a federal preschool program would likely force many preferred models out of business.We have tried the bureaucratic, top-down approach in K–12 education, and parents are clamoring for more options. There is no reason to expect more mandates and fewer options under a federal preschool program would improve opportunities for children.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.