Chairman Cardin, Ranking Member Paul, and Members of the Committee, thank you for the honor of participating in today’s hearing. My name is Aaron Yelowitz, and I serve as a Professor of Economics at University of Kentucky and a Senior Fellow at Cato Institute. My views expressed here today are informed by my research and reading of the literature on franchising and the role of the SBA in lending.

The franchising model – which allows aspiring entrepreneurs to adopt a business format that has proven to work while avoiding many of the growing pains and mistakes associated with a new business – impacts approximately 730,000 establishments and 8.4 million workers in the United States. Although many people associate franchising with the fast-food industry, there are thousands of franchise brands in approximately 300 business lines, including automotive, business-to-business services, cell phone repair, fitness, hair care, home repair services, tutoring, spas, childcare, pet care, and senior care. 1 Quick-service restaurants make up 25% of franchised establishments in the U.S., meaning the reach of the franchising model goes far beyond fast food.2

In a variety of contexts – from entry into markets, to jobs and wages, to the use of SBA business loan guarantee programs – emerging evidence shows that the conditions that franchisees operate under are not substantively different than owners of other small independent businesses. I’ll review pertinent numbers today from some compelling studies, which leads me to conclude that the motivation to single out the franchise model for additional regulation is unnecessary. Such regulation would likely increase costs and make the franchising model less viable, in turn leading to less entry, more exits, and ultimately less competition. Reduced market competition will increase consumer prices at a time when inflation is already at 40-year highs, thereby harming the American public.

The degree to which the federal government should be involved in regulating private businesses and subsidizing business loans is a legitimate question but singling out the franchisor-franchisee relationship is unwarranted. Furthermore, proposals to further regulate franchise disclosure that are solely confined to the SBA are misplaced from a policy perspective.3 Franchise sales and disclosure is heavily regulated by the Federal Trade Commission, which administers the FTC Franchise Rule, and requires franchise brands to offer disclosure in 23 areas.

Franchising and Economic Opportunity

Given the paucity of data to study the franchisor-franchisee relationship, Oxford Economics published a comprehensive study in September 2021 that offers many insights on the issues we are discussing today. The Oxford research team surveyed more than 4,000 individual franchisees across a vast array of industries, and asked about compensation, franchisor support, and involvement in the local community.

The first key takeaway is that franchising offers a path to entrepreneurship but is especially valuable for new entrepreneurs, veterans, minorities, and women. Some popular books describe the franchising model as “running a business with training wheels” – franchisors provide a set of training wheels to keep new franchisees balanced until they can pedal on their own.4 This viewpoint is robustly confirmed in the Oxford study. Overall, 32% of respondents report they would not own a business if they were not franchisees. The Oxford team calculates that without franchisor support, approximately 223,000 establishments employing some 1.8 million workers wouldn’t exist if franchising was not an option. The survey found that franchisees valued the franchisor’s support in the areas of training, meetings and events, and technology platforms. These are areas where a new entrepreneur running a small independent business would likely encounter growing pains and make mistakes.5 Intuitively, these responses are consistent with the idea that franchising provides a path to entrepreneurship, and many owners wouldn’t have gone down that uncertain path without such support.6

Franchising, Jobs, and Wages

Critics of franchising such as Professor David Weil often focus on the wage structure and labor violations.7 Weil’s central thesis is that in contrast to an idealized past in which large, vertically integrated employers dominated the American economy, today’s labor markets are characterized by a “fissured workplace,” in which employers have shed all non-core employees in order to reduce wages. Weil presents anecdotes of a handful of horror stories, but he doesn’t produce any evidence that franchise businesses pay less. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.

One of the mechanisms in the fissuring thesis is that franchisees have incentives to take short-cuts – including low wages – because they can free-ride off the brand’s reputation. The Oxford analysis of wages and wage growth compares franchised businesses to individually owned-and-operated businesses in 2018 and 2019, prior to the pandemic. The analysis used arm’s‑length data from the payroll company Homebase. Small, independent business owners have strong incentives to maintain their reputation, especially where social media postings claiming worker mistreatment can lead to viral stories, the loss of customers, and, paradoxically, make it even harder to recruit and retain staff. Yet wages and wage growth were virtually the same for newly hired workers in franchised businesses and independent ones. Wages grew from approximately $10.30 per hour at the start of employment to around $11.10 per hour after 20 months, with no more than a 13 cent difference in any month. Moreover, newly hired workers in franchised businesses were more likely to be promoted to manager.

Finally, the Oxford survey of 4,000 franchisees found that the share of workers offered various benefits at small franchise firms was on par with the share at small non-franchise establishments. This datadriven descriptive evidence presents no support for the fissuring hypothesis.

Franchising and SBA Lending

SBA loans are a tiny share of the total banking business, accounting for about 1% of all small business loans.8 A recent peer-reviewed Journal of Finance study links SBA loans to the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Database, to compare similar businesses that either received or did not receive an SBA loan guarantee. SBA loans did encourage job growth of 3.0 to 3.5 jobs per million dollars of loan, suggesting real effects of credit constraints. Over the 1992 to 2007 period, the study estimated total job creation in the range of 690,000 to 813,000 from SBA loans in the 7(a) and 504 loan programs. However, this is about 5 to 10 times smaller than the 5.6 million job figure that applicants predicted as part of “jobs supported.” The taxpayer cost – from loan default charge-offs and other administrative costs – ranged from $21,580 to $25,450 per job created. To put this in perspective, the study estimates that the jobs created by the SBA program pay an average of $30,000 per year.

Business lending is important to franchisees; the Oxford survey finds that 21% of respondents report being capital constrained when starting their first franchise business and that being a franchisee provided them with access to capital. Nonetheless, there are concerns about default rates among franchisees.9

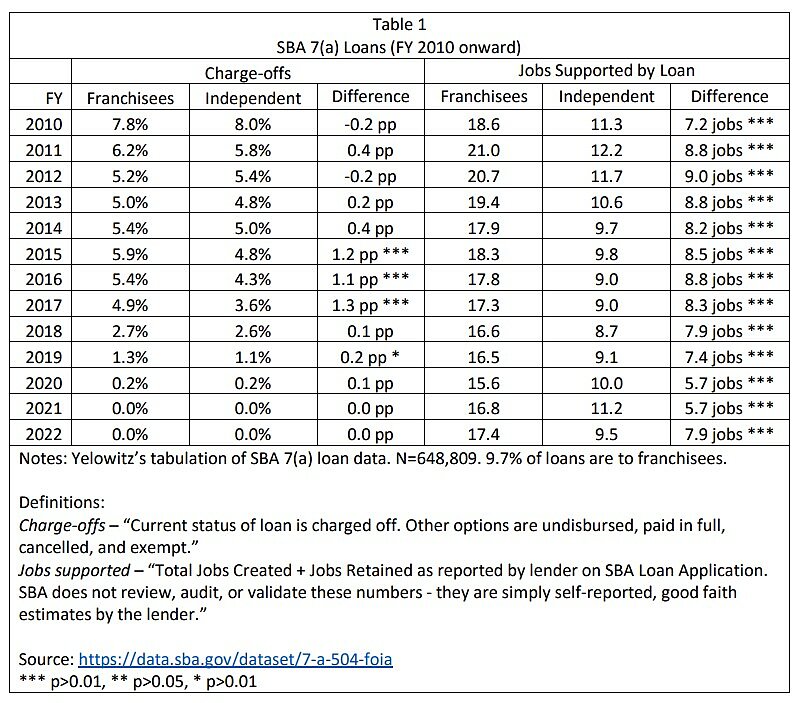

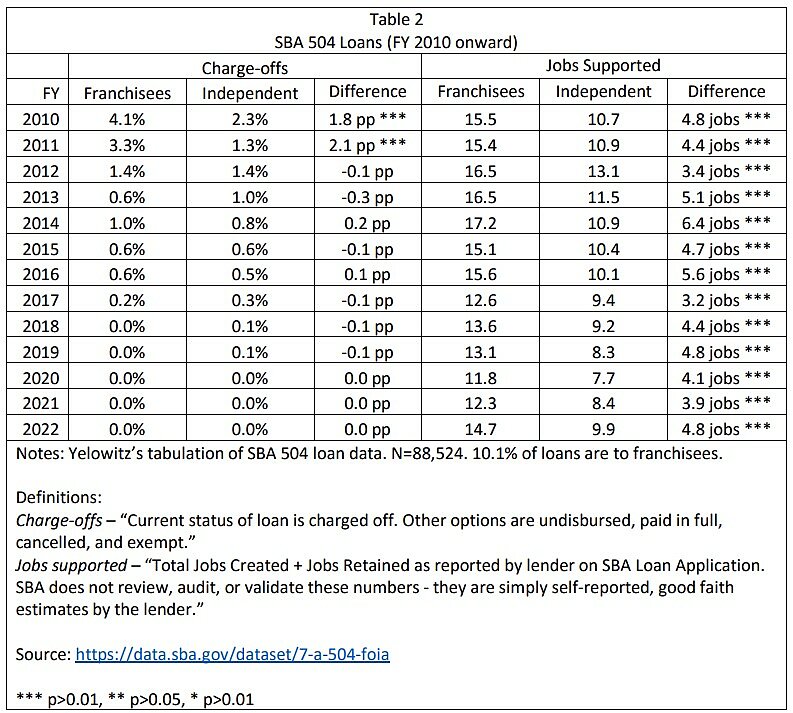

I’ve recently analyzed SBA loans from publicly available data on the SBA webpage; I will caution that this analysis is preliminary.10 The tables show loan performance from Fiscal Year 2010 onward based on franchise status – essentially a comparison of franchisees and independent businesses.11 For technical reasons dealing with how lenders input franchise status during the loan process, any difference in charge-offs for franchisees is likely overstated for loans prior to 2018, yet even with these technicalities there is virtually no difference in charge-offs.12 For SBA 7(a) loans, there are nearly 650,000 loans, of which 9.7% were to franchisees. For SBA 504 loans, there are nearly 90,000 loans, of which 10.1% were to franchisees. As more time lapses, there is greater possibility of charge-offs, although the charge-off rate for 2020 through 2022 may be misleading because there has been debt relief forbearance for existing and new 7(a) and 504 loans from the CARES Act.

In my view, the tables show very modest differences in charge-offs in the SBA data. Between fiscal years 2010–2014 as well as 2018 onward, the difference in charge-offs between franchisees and independent businesses is statistically insignificant for the 7(a) loan program. For example, in FY 2010, 7.8% of franchisees’ SBA loans were charged off, slightly lower than the 8.0% for independent businesses. Between the years 2015 and 2017, the difference is significant with an estimate of around 1.0 percentage point (pp). The same patterns emerge in the 504 loan program, where charge-offs were nearly the same for all years after 2011. In contrast, the jobs supported by franchisees – for both the 7(a) and 504 programs – are markedly higher for franchisees than independent businesses.

In conclusion, there is no clear motivation to single out the franchisor-franchisee relationship. Much like the out-of-context characterization of franchisee wages and wage violations in Weil’s book, the SBA data do not support the characterization of franchisee loan charge-offs in Senator Cortez Masto’s report as anything out of the ordinary.13 Rather than being squeezed by corporate franchisors to commit wage violations and default on loans, the data paints a picture of franchisees performing much like small independent businesses.

Franchising Legislative Proposals, Competition, and Consumer Prices

Small businesses such as those created by franchising promote competition and increase the variety of goods and services for consumers. Some recent legislative proposals would impose new regulatory burdens on the franchisor-franchisee relationship, which is a private, voluntary, and mutually beneficial agreement. For example, the proposed “Protecting the Right to Organize” Act, or the PRO Act, would codify into law an expanded “joint employer” standard, whereby franchisors can be held responsible for actions taken by their franchisees.14 The so-called “ABC test” – also included in the proposed PRO Act – could potentially classify franchisees as employees of their brand, instead of small businesses, which in reality they are. This would essentially eliminate the entire concept of franchising as a business model. Both provisions would discourage entry, encourage exits, and ultimately lead to fewer franchised establishments in the marketplace. In turn, this would lead to reduced competition and higher consumer prices.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.