Chairman McClintock, Ranking Member Jayapal, and distinguished members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Alex Nowrasteh, and I am the Vice President for Economic and Social Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, a nonpartisan public policy research organization in Washington, D.C. It is an honor to be invited to speak with you today on the topic: “Restoring Integrity and Security to the Visa Process.”

Over many decades, the Cato Institute has produced original research on the costs and benefits of immigration to Americans, groundbreaking research on the hazard of foreign-born criminality and terrorism in the United States, and analyses of the visa security system. I’m happy to report that the benefits of immigrants to Americans vastly exceed the costs, the hazard posed by immigrant criminals and terrorists who enter on nonimmigrant visas is small, and the current visa process is secure.

This testimony will focus on the actual security effects of migration, specifically nonimmigrant visa holders, as evidence of the effectiveness of current security and vetting procedures. The actual effects are a more valuable criterion than endlessly discussing the nuances of different vetting procedures inside government agencies or data sharing with foreign governments. The security proof is in the pudding, not in the quality of the paper or typeface of the pudding’s recipe.

Terrorism and Crime Committed by Nonimmigrant Visa Holders

Nonimmigrants who enter the United States on a visa have low rates of criminality and pose a minuscule terrorism hazard. This is evidence of at least one proposition, probably two. First, the visa security and vetting system works very well at excluding those who would seek to harm Americans. Second, there just aren’t that many criminals or terrorists who want to come to the United States to do us harm. This testimony will mostly focus on the

The best evidence that the visa process is secure and vetting is effective is the small number of people killed or injured in terrorist attacks committed by those on nonimmigrant visas and the low legal immigrant crime rates.

There were 237 foreign-born terrorists who committed attacks on U.S. soil, intended to commit attacks on U.S. soil, threatened attacks here, or tried to fund domestic terrorism.1 They are responsible for 3,046 murders and 17,083 injuries in attacks on U.S. soil from 1975 through the end of 2024. The annual chance of being murdered in a terrorist attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist during that time is about 1 in 4,559,768, and the annual chance of being injured is about 1 in 813,033. By comparison, the annual chance of being murdered in a criminal non-terrorist homicide in the United States was about 1 in 13,880 during the same period. During that time, 97.8 percent (2,979) of all those murdered in terrorist attacks were murdered on 9/11, and 86.9 percent (14,842) percent of all people injured in foreign-born terrorist attacks were injured on 9/11. Foreign-born terrorists who entered on a nonimmigrant visa are an even smaller share, accounting for 3,006 murder victims in attacks during those years and 99.1 percent during the 9/11 attacks.

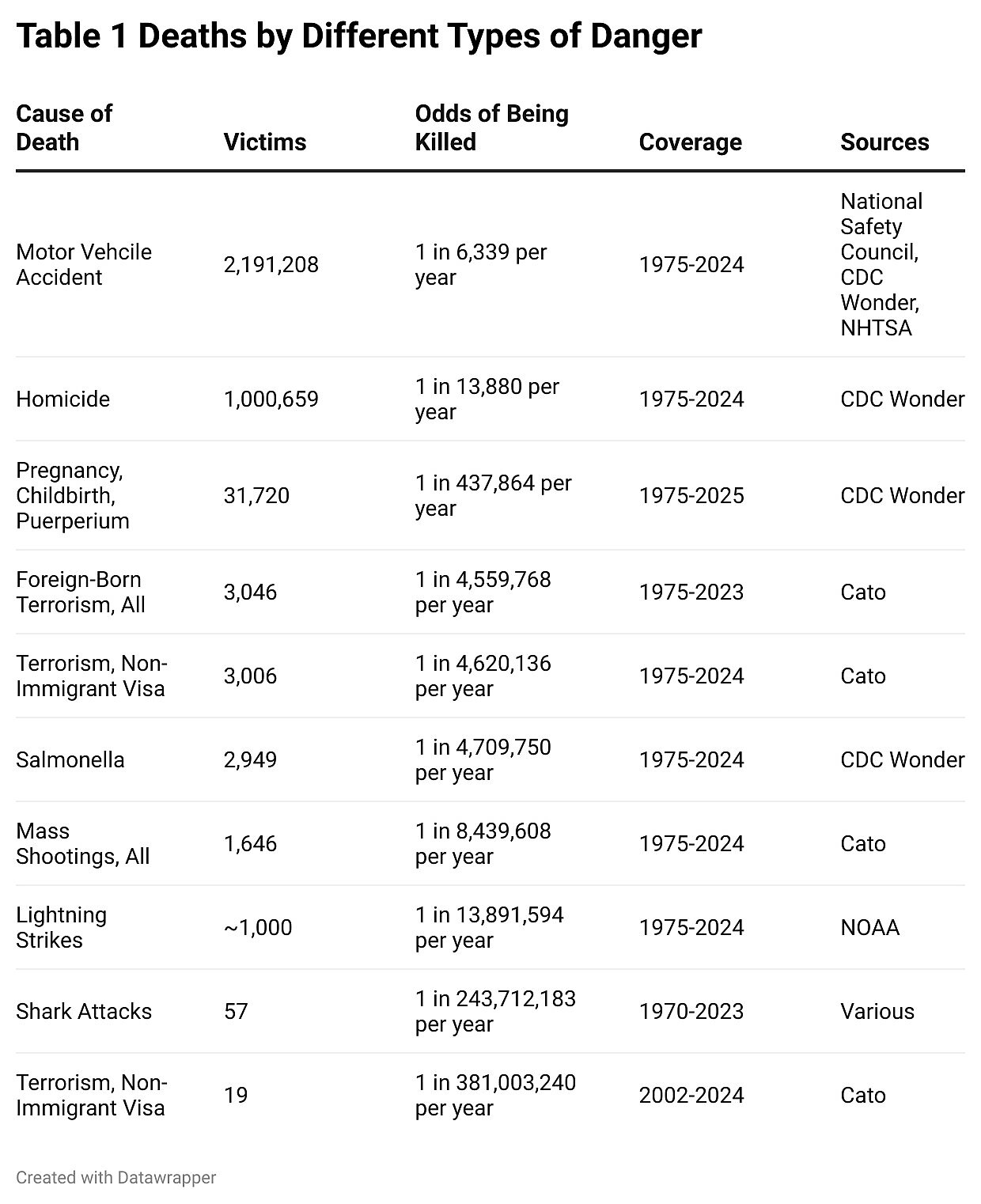

The historical nonimmigrant terrorist data aren’t very useful for understanding the current vulnerabilities in the visa system because security procedures were overhauled after the 9/11 attacks.2 Including deaths from the 9/11 attacks in an analysis of visa security procedures in 2025 would be like trying to understand the modern risk of surgery by using data from before the invention of antibiotics. Thus, the most important number to focus on is 19, which is the total number of people killed by nonimmigrant terrorists on US soil since 9/11, when the visa security system was overhauled. The chance of being killed by a terrorist who entered on a nonimmigrant visa is about 1 in 381,003,240 per year. The annual chance of being killed in a shark attack is about 56 percent greater than by a nonimmigrant terrorist after 9/11, the chance of being killed by a lightning strike is about 27 times greater, the chance of being murdered in a normal homicide is about 27,450 times greater, and the chance of dying in a motor vehicle crash is about 60,105 times greater (Table 1).

The chance of being murdered in an attack committed by nonimmigrant terrorists is so small that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would label them as “unreliable.” Motor vehicle accidents, homicide, and pregnancy-related deaths are all substantially more hazardous than foreign-born terrorists. Yet, people still choose to drive in motor vehicles, live in American cities, have children, and eat food because the benefits of those activities outweigh the costs. Likewise, the benefits of nonimmigrants coming to the US on properly vetted visas still outweigh the costs.

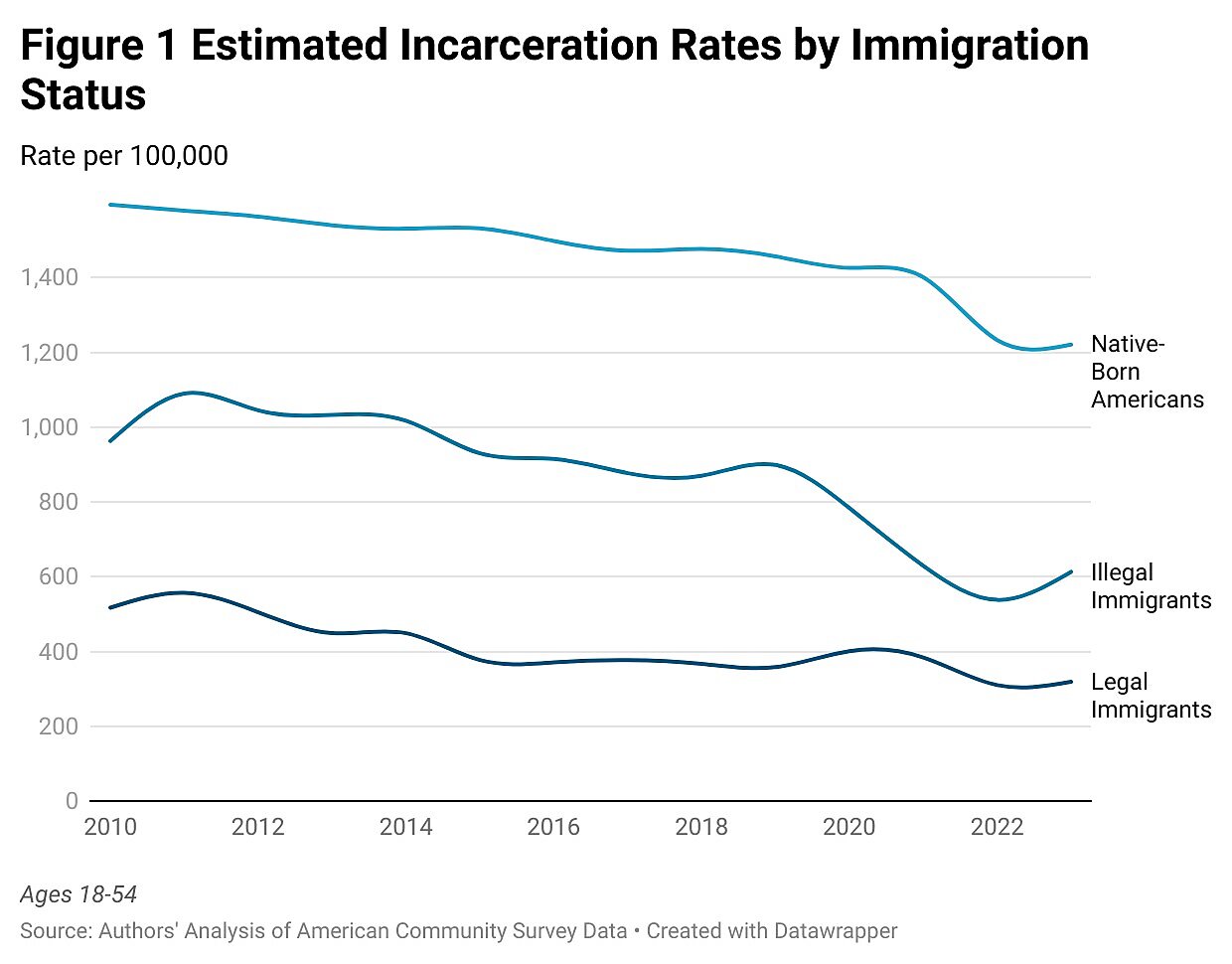

Legal immigrants have a nationwide incarceration rate of 319 per 100,000 in 2023, which includes nonimmigrants admitted on visas (Figure 1). By comparison, illegal immigrants have an incarceration rate of 613 per 100,000, and native-born Americans have an incarceration rate of 1,221.3 Data from Texas also show that the legal immigrant homicide conviction rate was 62 percent below native-born Americans in 2022, and their overall criminal conviction rate was 58 percent below the native-born American rate.4

Table 2 shows the 2023 incarceration rates for all countries reported or rumored to limit their sharing of crime and national security data with the US government. The fear is that a lack of data sharing allows many criminals to enter the United States. However, immigrants, migrants, and travelers from all those countries have incarceration rates below those of native-born Americans. Perhaps those rates would be lower with full data share, but there is not a good argument to close down immigration or travel with those countries based on current crime data.

Trump’s Immigration Bans Will Have No Detectable Effect on Terrorism or Crime

Egyptian-born Mohamed Sabry Soliman entered the United States on a tourist visa in August 2022 and filed for asylum in September.5 On June 1, 2025, Soliman injured 15 people in a terrorist attack in Boulder, Colorado. President Trump used this heinous crime to announce travel and immigration restrictions on 19 countries, none of which were Egypt, and that had collectively sent terrorists to the US that have murdered six people in terrorist attacks on US soil since 1975, one since 9/11.6 President Trump’s June 4th proclamation doesn’t even mention terrorism as a concern for most of the restricted countries.7

The administration recently proposed restrictions on additional countries to take effect this week unless they make visa security improvements.8 Since the visa security and screening system was overhauled 9/11, migrants and travelers from these countries murdered seven people in terrorist attacks on US soil for a 1 in 905 million per year chance.

According to US Census and American Community Survey Data, travelers and immigrants from the banned and restricted countries (as of June 23, 2025) have a nationwide incarceration rate of 370 per 100,000 in 2023 for the 18–54 aged population, 70 percent below that of native-born Americans.9

The hazard posed by foreign-born terrorists was low during the Biden administration by historical standards, at least judging by the number of deaths in attacks. The Biden administration was the first administration since at least President Ford where zero people were murdered in an attack committed by foreign-born terrorists on US soil. This is a widely unreported fact, considering the fear of terrorism that was promulgated during the Biden administration.

The Terrorist Threat Posed by Iran

President Trump entered another Middle East war on June 21, 2025, when the US Air Force bombed Iran. The Islamic Republic of Iran is a weak and feckless state on the other side of the world, but it has a deep history of funding and supporting terrorist attacks. Iran probably does pose a relatively elevated terrorist threat to the United States currently, but it’s relatively small. Even so, this assessment is unscientific and vague, and the threat is so small that it shouldn’t change current US policy. The US government doesn’t even take the threat of domestic terrorism that seriously, as they rank the cybersecurity threat from abroad above the violent terrorism risk on US soil.10

Twelve terrorists from Iran have attempted or committed attacks on US soil since 1975. They have murdered zero people and injured nine. Mohammed Reza Taheri-azar and Manssor Arbabsiar were the only two Iranian-born terrorists who committed attacks in 2006 and 2011, respectively.11 Taheri-azar was clearly insane and undirected by the Iranian government. Arbabsiar was hired by the government of Iran to assassinate the Saudi ambassador.12 The Arbabsiar plot was mostly a fiction facilitated by the US government to catch people like Arbabsiar, and it was never a serious threat. Another unserious plot planned by Iranian officials overseas was led by Farhad Shakeri, an Afghan, who was deported from the United States in 2008 after a prison sentence for robbery. His plan was to hire former inmates from prison to assassinate President-elect Trump and some anti-Iranian activists at the behest of the Iranian government and in revenge for the US killing of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp commander Qasem Soleimani under President Trump’s order in 2019.13 The Iranian government’s revenge plot for killing a national military hero involved an Afghan criminal deported from the United States in 2008, coordinating from Iran with some of his prison buddies.14 It sounds like the plot of a black comedy with results almost as absurd.

Iranian proxies from Hezbollah could pose a threat but there have only been two arrests of Hezbollah operatives on US soil who were plausibly involved in plotting domestic attacks. Ali Kourani and Alexei Saab were arrested in 2017 and 2019, respectively, and they were reportedly members of Hezbollah Unit 910.15 Israel recently reduced Hezbollah’s power in Lebanon to a small fraction of its former exaggerated strength. There aren’t likely any terror plots planned by Hezbollah in the United States and, if there were, they likely would have carried out attacks at the height of the Israel-Hezbollah war. American military personnel in the Middle East face a far greater threat from Iranian retaliation than Americans in the homeland do.

Visa Security and Vetting Procedures

The U.S. Department of State (DOS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) share the responsibility of vetting nonimmigrant visa applicants through a thorough and multi-layered process. U.S. Embassies and Consulates, operated by the DOS, handle visa applications and initial screening. DHS provides security checks and makes final admission decisions at ports of entry. Below is a simplified explanation of the security and screening process for nonimmigrant visa applicants.

Standard Vetting Procedure for Nonimmigrant Visas

The first step combines the visa application and initial data collection. All nonimmigrant visa applicants begin by submitting the Online Nonimmigrant Visa Application (Form DS-160), which collects comprehensive biographical information, travel plans, and background details.16 Since 2019, the DS-160 also equires applicants to provide social media identifiers used in the past five years that are now being used to screen for speech that would be first amendment protected if uttered on US soil.17 Applicants must also upload a recent photograph meeting DOS requirements and answer security-related questions about criminal history, immigration violations, and other related inquiries. Once the DS-160 is submitted, the data is stored in the Consular Consolidated Database (CCD) and made accessible to consular officers and screening systems. At this stage, applicants pay the non-refundable visa application fee and obtain an appointment for an in-person interview at a U.S. Embassy or Consulate.18

The second step is the consular interview and collection of biometric identity information. With some exceptions, nonimmigrant visa applicants between ages 14 and 79 are required to appear for a visa interview with a consular officer.19 During the interview, the consular officer reviews the application, asks about the purpose of travel and ties to the home country, and evaluates the applicant’s eligibility under U.S. immigration law. During the interview, consular officers typically collect digital biometric data that include all ten fingerprints scanned electronically and a digital photo.20 This information is all stored in the CCD system where DHS officials verify that the biometrics are consistent with the person’s identity and then further check the data against U.S. security databases such as DHS IDENT (more on this below). Consular officers also verify that required supporting documents are in order.21

The third step includes security screening and inter-agency checks. While the consular interview is taking place and continuing afterward as needed, multiple security checks are run on every applicant. The consular officer uses the State Department’s Consular Lookout and Support System (CLASS) to perform name-checks across numerous watchlists and databases.22 CLASS is an interagency database that contains records from many U.S. government sources, including prior visa refusals, immigration violations, criminal histories, terrorism watchlists, intelligence reports, and even certain civil records. CLASS incorporates data from the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center (TSC) watchlist, the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), INTERPOL notices, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and extracts of the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) on wanted persons and fugitives.23 This process automatically screens a visa applicant’s name and aliases against multiple law enforcement and intelligence databases and records for any derogatory information or matches to known or suspected threats.

In addition to the name and alias checks, the applicant’s fingerprints are also screened against biometric databases. As mentioned above, the State Department forwards the 10-print scans to the DHS Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) and to the FBI’s Next Generation Identification (NGI) system for criminal history checks. The fingerprint check through FBI NGI will reveal any past criminal arrests or convictions tied to the applicant’s fingerprints, as well as any national security records through various watchlists. The DHS IDENT check will reveal any prior immigration encounters under any identity. IDENT also includes immigration violation records and lookout information shared by various agencies, and it ensures that biometric data from the visa application is available to DHS officers at U.S. ports of entry for identity verification. In practice, the State Department transmits applicants’ biometric and biographic data to DHS’ Office of Biometric Identity Management, which compares and shares the data with partner agencies.

The fourth step is enhanced interagency vetting, which is only used if needed. Except in rare cases, the automated watchlist and biometric checks clear within a short time, and the consular officer can make a decision. However, if the initial screenings reveal possible concerns, the migrant visa application undergoes Administrative Processing, also known as Security Advisory Opinion processing. In these unusual cases, the consular officer temporarily refuses the visa under section 221(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act and seeks additional information before a final decision.24. The case may be sent for review by specialized units in Washington, D.C. and other agencies. For example, if an applicant’s name is similar to a person of interest, or the applicant’s background involves sensitive scientific fields, the post may initiate a Security Advisory Opinion (SAO) request to consult agencies like the FBI, CIA, or Departments of Defense before proceeding.25

DHS is directly involved in screening visa applications even before visas are issued, especially in overseas posts with a predetermined higher risk of terrorism. Under the Visa Security Program (VSP), which is authorized by Section 428 of the Homeland Security Act, Homeland Security Investigations agents are stationed at 45 consular posts in 29 countries to screen and vet visa applicants for terrorism and criminal risks.26

In the last several years, DHS has deployed advanced automation for this process. For example, CBP’s National Targeting Center (NTC) receives electronic visa application data in real-time and uses the Automated Targeting System — Passenger (ATS‑P) to automatically screen every visa applicant’s data against U.S. terrorism and law enforcement databases.27 According to DHS, ATS‑P checks 36 different data points from the DS-160 (such as names, dates of birth, passport numbers, and other identifiers) against the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Database and CBP’s own enforcement system (TECS).28 If no derogatory information is found, the system will electronically advise the consular post that DHS won’t issue the visa.

If a potential match or concern is flagged, CBP officers and ICE agents at the NTC perform manual vetting, researching the applicant in over 40 specialized databases to confirm whether the hit is valid.29 This could include deeper checks into intelligence reports, travel history, immigration records, social media posts, and other open-source information. For cases that remain suspicious, the on-site ICE Visa Security Unit agents will conduct further investigation and coordinate with the consular officer, often issuing a recommendation to refuse the visa if the applicant poses a security threat. In this way, DHS and DOS share data and expertise at the visa adjudication stage. The State Department retains final authority to issue or refuse the visa, but DHS contributes critical information and can effectively block visas being issued to known or suspected threats through the VSP screening process. The National Vetting Center (NVC) was established in 2018 to provide a centralized interagency platform to support vetting. NVC began with CBP’s Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) and supported vetting for Enduring Welcome, Uniting for Ukraine, and the. Venezuela Migration Enforcement Process.30 Since 2022, the NVC’s process has been formally supporting the nonimmigrant visa vetting process by integrating intelligence agency inputs into visa vetting while still leaving final determinations to DOS.31

The fifth step is visa adjudication and issuance. If the migrant applicant passes all security checks and meets the visa’s requirements, the consular officer will approve the visa application. At that point, DOS stamps the migrant’s passport with a machine-readable visa, which includes the applicant’s photo and encoded data. If the visa cannot be approved, the consular officer will formally refuse the visa.

The sixth step is the migrant’s arrival at a DHS port-of-entry for inspection. When the migrant visa holder arrives at a U.S. port of entry, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers conduct a final vetting and make the determination whether to admit the visa holder.32 Advanced Passenger Information transmitted by airlines allows CBP officers to run initial checks even before arrival. CBP also often takes a live photo for facial comparison, reviews information, and asks the migrant questions. CBP officers also check that the migrant is carrying other required documents. The consular vetting and border check process is largely redundant. The standard process involves multiple layers of checks from two agencies and multiple subagencies.

Visa-Specific Differences in Security and Vetting Procedures

The core vetting steps above apply to applicants on all nonimmigrant visas, but certain visa classes have additional specific checks. This section will detail those specific additional checks for B visas and F‑1 and M‑1 visas.

- B‑1/B‑2 Visitor Visas: B‑1 visas for business and B‑2 visas for tourism are among the most common and are generally processed following the standard procedure. The main vetting focus for a visitor visa is ensuring the applicant’s true intent is temporary and in line with the visa and that they have strong ties abroad to incentivize their return.33 In addition to the standard security checks, consular officers scrutinize the applicant’s personal circumstances and travel history for red flags. Fraud prevention is a priority in B‑1/B‑2 cases due to the volume of applications. Aside from the Electronic Visa Update System for visitors from China, the vetting of B visas is largely uniform. All are checked against the same watchlists and undergo the same fingerprint screening with occasional interview waivers for certain low-risk renewal applicants.

- F‑1 and M‑1 Student Visas: Students must also meet specific educational and regulatory requirements in addition to clearing all the security checks above. One specific requirement is the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), a DHS program that manages schools authorized to host international students. Only a student accepted by a US school that is SEVP-approved can apply for an F‑1 or M‑1 visa. The school issues a Form I‑20 to certify the student’s eligibility and enters his information into the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS), a DHS database.34 Consular officers then assess whether the school is legitimate, the student’s ability to pay tuition, the student’s ability to support themselves in the US, whether their field of study has sensitive national security implications and other aspects of the application they are ill-equipped to objectively assess. Additions to the Foreign Affairs Manual in March and April 2025 are secret and unavailable to the public.35 The administration has recently added several additional requirements for student visas to report disciplinary actions and other events.36 In June 2025, DHS announced expanded vetting for F, M, and J visa applicants that includes closer review of their social media accounts.37

Conclusion

The title of this hearing assumes that integrity and security are missing from the nonimmigrant visa process. That is false and has never been further from the truth. Nonimmigrant visas are not particularly dangerous, especially after the security and vetting reforms following the 9/11 attacks. At best, the vetting procedures currently in effect reduce the threat of terrorism and crime. At worst, they are completely unnecessary because the threat from foreign-born terrorism and crime is minimal. Regardless, there is no security process to restore because none has been lost.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.