Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Toomey, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for holding today’s hearing, titled “Reauthorization of the National Flood Insurance Program: Protecting Communities from Flood Risk,” and for providing me the opportunity to testify before you. My testimony draws heavily from my recently-published Cato Policy Analysis, titled “The National Flood Insurance Program: Solving Congress’s Samaritan’s Dilemma.”1

Introduction

The U.S. government has often come to the financial assistance of Americans harmed by mass calamity. Even in the Founders’ era, in 1803, Congress enacted a form of disaster relief by suspending for several years the bond payments owed by Portsmouth, N.H. merchants after a fire struck the seaport. (In keeping with the young nation’s values, President Thomas Jefferson also anonymously donated $100—the equivalent of $2,400 today—for humanitarian aid to the city’s residents.2)

The impulse for government-provided disaster assistance is understandable. But public aid crowds out private relief and dampens incentives for private insurance and damage prevention. On the international level, economists Paul Raschky and Manijeh Schwindt of Australia’s Monash University tested for this effect using data from 5,089 natural disasters in 81 developing countries over the period 1979–2012. They found that “past foreign aid flows crowd out the recipients’ incentives to provide protective measures that decrease the likelihood and the societal impact of a disaster.”3

Policymakers thus face what is known as the Samaritan’s dilemma4: the choice to either render aid after catastrophes or else, seemingly heartlessly, withhold aid to incentivize people in calamity-prone areas to purchase disaster insurance, take preemptive private and local public measures to reduce losses, and build robust private charity systems for when catastrophe strikes. To achieve the latter, elected policymakers must effectively “precommit” to not rendering financial aid, warding against the temptation to be “time inconsistent” and backtrack when the public sees heart-rending images of disaster victims.

The National Flood Insurance Program

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in 1968 to escape the Samaritan’s dilemma in a politically palatable way. In prior decades, lawmakers had routinely handed out ad hoc aid to flood and storm victims. The NFIP was intended to reduce such aid and protect federal taxpayers while providing prospective flood victims a way to financially protect against loss.

The NFIP is a government program, but lawmakers wanted it to charge most insureds roughly “actuarially fair” premiums. Though buildings constructed prior to the legislation would qualify for discounted rates (and thus receive public subsidy), owners of subsequently built structures who purchased coverage would de facto “prepay” the cost of restoring their properties following catastrophe. The program also requires that, for buildings in high-risk areas to qualify for coverage, those areas must be zoned to limit construction, and their building codes must include provisions to make new structures better able to withstand floodwaters, e.g., by requiring their main levels to be elevated above typical floodwaters.

Except for the “grandfathered” preexisting structures, lawmakers intended for the NFIP to be largely subsidy-free, protecting taxpayers. The 1966 task force report that gave rise to the NFIP originally estimated that federal subsidization of the cost of flood premiums for existing high-risk properties would be required for a limited period of time only—approximately twenty-five years—a prediction that would prove to be wildly optimistic.5 The percentage of subsidized policies has decreased over time, but now—after a half-century of the program—they have not disappeared. And in the past decade, Congress has partly retreated from the commitment to end the subsidies.

So, what should be done about flood disaster policy going forward? Though private flood insurance has entered the market in the last few years, there are serious questions whether it will persist over the long term. And elected policymakers are highly unlikely to ignore the plight of large groups of people whose homes are struck by floodwaters. Yet, a return to the ad hoc aid of the mid-20th century is undesirable. So, though flawed, the NFIP likely is the best policy response that is politically attainable. That said, the program can be improved, and the most important step Congress can take is to return to the original intention that the NFIP charge unsubsidized, actuarially fair rates for covered structures.

Pre-NFIP Federal Disaster Policy

Between 1803 and 1947, Congress enacted at least 128 specific legislative acts offering ad hoc relief after disasters.6 But some disasters were followed by no federal response. For example, in 1887 President Grover Cleveland vetoed drought relief for Texas.

Until the 1960s, federal disaster policy mostly focused on engineering solutions rather than relief. For instance, in 1879 Congress created the Mississippi River Commission to coordinate private levee projects to avoid the problem of one area “solving” its flooding problems by building levees to divert the waters to other areas. But Midwest businessmen lobbied for a sustained federal financial commitment to manage Mississippi floods. Congress authorized a round of federal flood control spending as part of the Mississippi River Commission’s work in 1917 and again six years later, but local funding was still required to cover one-third of the works’ costs.7

The Great Mississippi River Flood of 19278 resulted in permanent federal responsibility for controlling flooding along the river under the Flood Control Act of 1928. That responsibility expanded to the entire country in the Flood Control Act of 1936.9 This aid was overwhelmingly directed to building flood control projects.10

This began to change with the Disaster Relief Act of 1950 (now known as the Stafford Act), which assumed federal responsibility for the repair and restoration of local public infrastructure after disasters.11 Overall, federal responsibility for disaster recovery spending began to grow. From 1955 through the early 1970s, federal disaster relief expenditures increased from 6.2 percent of total damages after Hurricane Diane in 1955 to 48.3 percent after Tropical Storm Agnes in 1972.12

The History of Private Flood Insurance

At various times in American history, private insurers have offered flood coverage. But the magnitude of losses from major floods frequently pushed insurers into bankruptcy, and until very recently, no reputable insurer had offered flood insurance since the 1927 Great Mississippi Flood. As Wharton School economist Howard Kunreuther and others explained in a 2019 paper:

In 1897, an insurance company offered flood insurance to property along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers motivated by the extensive flooding of these two rivers in 1895 and 1896. Two floods in 1899 not only caused the insurer to become insolvent since losses were greater than the insurer’s premiums and net worth, but the second flood washed the office away. No insurer offered flood coverage again until the 1920s, when thirty fire insurance companies offered coverage and were praised by insurance magazines for placing flood insurance on a sound basis. Yet, following the great Mississippi flood of 1927 and flooding the following year, one insurance magazine wrote: “Losses piled up to a staggering total…. By the end of 1928, every responsible company had discontinued coverage.”13

Can private flood insurance be economically viable? Much scholarly discussion on this question has been vague rather than definitive: “The experience of private capital with flood insurance has been decidedly unhappy,” wrote two academics in a 1955 book.14 “From the late 1920s until today, flood insurance has not been considered profitable,” noted the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in a 2005 report.15 Kunreuther and others quote a commenter in a May 1952 industry publication offering this blunt assessment:

Because of the virtual certainty of the loss, its catastrophic nature, and the impossibility of making this line of insurance self-supporting due to the refusal of the public to purchase insurance at rates which would have to be charged to pay annual losses, companies could not prudently engage in this field of underwriting.16

Government Insurance

With no private flood insurance available to property owners, Congress in the mid-20th century took on an increasing role in providing disaster relief. But lawmakers realized that in doing so they were placing a growing burden on taxpayers.

When Congress appropriated relief funds for Hurricane Betsy and other storms that devastated the South in 1963 and 1964 and flood losses on the upper Mississippi River in 1965, the legislation included a provision directing the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to study whether a federal flood insurance program would be a desirable alternative to ad hoc disaster relief.17 The resulting 1966 report recommended such a program, adding that any federal premium subsidies should be limited to existing structures in high-risk areas, while new construction should be charged actuarially fair rates.18

Congress enacted the National Flood Insurance Act in 1968, incorporating most of the HUD study’s recommendations. Though structures erected prior to the full implementation of full implementation of the legislation qualify for subsidized premiums, all other covered structures ideally pay full actuarial rates although only for floods estimated to occur with at least 1 percent annual frequency.19 More rare floods, so-called catastrophic events, with an annual probability of less than 1 percent, are implicitly insured by the Treasury. Flood-prone areas that are eligible for NFIP coverage are designated on Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) that were drawn and are periodically updated under the legislation. According to a 2015 National Research Council (NRC) report, “The expectation was that, over time, the properties receiving pre-FIRM subsidized premiums would eventually be lost to floods and storms and pre-FIRM subsidized premiums would disappear through attrition.”20

But details of the 1968 legislation meant that even “unsubsidized” NFIP premiums do not fully cover the costs of the catastrophes striking those properties. For instance, the NRC report explains, “The legislation stipulated that the US Treasury would be prepared to serve as the reinsurer and would pay claims attributed to catastrophic-loss events.”21 A reinsurer is, in essence, an insurer for the insurer, so federal taxpayers ultimately backstop the NFIP program in the event of severe losses. As a result, even post-FIRM buildings receive some degree of subsidy.

Land-Use Controls

Actuarial fair rates were only one way the NFIP was supposed to reduce taxpayer exposure to losses. The statute also included zoning requirements to limit construction in flood-prone areas and building code requirements intended to make structures built in those areas less vulnerable to flood damage.

Under the 1968 law, federal flood insurance is available only in communities that agree to land-use controls that limit construction in a high-risk area—a so-called “100-year floodplain,”22 known officially as a Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA). Structures in communities that have not adopted those zoning controls cannot receive mortgages sponsored by or sold to any federal agency, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Veterans Administration.23 According to University of Florida law professor Christine A. Klein:

Such regulation would constrict the development of land which is exposed to flood damage and minimize damage caused by flood losses. Second, regulation would guide the development of proposed future construction, where practicable, away from locations which are threatened by flood hazards.24

Though Congress intended for construction to retreat from the floodplains, NFIP rules have always allowed new construction in the zones provided that the structure’s first floor is elevated above the high-water level predicted to occur with 1 percent annual probability, the so-called Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The 1968 statute also requires elevation for pre-FIRM properties that subsequently are “substantially damaged or substantially improved, which triggers a requirement to rebuild to current construction and building code standards.”25 From the beginning of the program, federal regulation has defined “substantially damaged and substantially improved” as repairs or alterations that equal or exceed 50 percent of the market value of the structure before damage or renovation occurred.26 So, despite the initial intent of the 1968 legislation to abandon structures and development in floodplains, the rules quickly allowed rebuilding—with elevation and engineering improvements.

Making NFIP Subsidies Disappear?

The inclusion of these land-use and building code provisions in addition to true actuarial pricing has been justified historically as lawmakers attempting to curtail moral hazard.27 At least that was the thinking in 1968.28 But this justification does not make sense for two reasons.

First, if homeowners pay higher premiums that adequately cover the risk presented by their vulnerable, non-flood-proofed homes, there is no moral hazard, strictly speaking. The higher premiums incentivize structure owners to elevate their buildings if the cost of doing so plus the present value of the lower premiums associated with elevation is less than the present value of the premiums for un-elevated structures. Also, regardless of whether a structure owner elevates, if the premiums for pre-FIRM structures were not subsidized, the government and taxpayers should be indifferent to paying claims for repetitive losses.29

Second, moral hazard is an increase in the incidence of damages (by those who are insured) relative to the incidence used by insurance companies to calculate the rates because of unobserved behavior on the part of insureds that increases the incidence. But it is easy to observe whether a structure’s first floor and important utilities (heating, air conditioning, hot water, and telecommunication and electrical interfaces) have been elevated above the BFE when assigning it to an actuarially fair rate class. Thus, though “moral hazard” is offered as a rationale for employing land-use and building-code controls in addition to actuarial prices, the term apparently is being used in a casual rather than rigorous fashion.

The more likely reason for these requirements is to further protect lawmakers from the Samaritan’s dilemma. Members of Congress and the executive branch appreciate the political forces associated with disaster relief. Given constituents’ desire for government-provided aid, the land-use and building-code requirements can be seen as a commitment device to eliminate, over time, the subsidies for the grandfathered pre-FIRM structures. Eventually, all pre-FIRM structures would be abandoned or rebuilt in such a way that they would not be subject to flooding losses.

And overall, this bit of political engineering appears to have been successful. The percentage of NFIP-covered structures receiving pre-FIRM subsidies fell dramatically over the first five decades of the program. Some 75 percent of covered properties received this subsidy in 1978, but only about 28 percent in 200430 and 13 percent in September 2018.31

It should be noted that the elevation requirement does not appear to be rigorously enforced. A 2020 New York Times investigation revealed there are 112,480 NFIP-covered structures nationwide with first floors below BFE paying premiums that are not reflective of that risk. The owners of those properties filed 29,639 flood insurance claims between 2009 and 2018, resulting in payouts of more than $1 billion, an average of $34,940 per claim.32

The NFIP also includes cross subsidies between different groups of insureds. One instance reflects the type of flooding a property is subject to. Within the 100-year floodplain, land is divided into two categories: one for coastal areas that face tidal flooding (“V” zones) and thus are especially high-risk and should pay higher actuarially fair rates, and the other for ordinary, non-tidal flooding (“A” zones).33 A property that is initially mapped in zone A and is built to the proper building code and standards, and then later is remapped to higher-risk zone V, is entitled to continue paying zone‑A premiums if the property has maintained continuous NFIP coverage. That subsidy is financed by other NFIP participants, who pay premiums above actuarially fair levels.

Another instance involves the remapping of BFE levels. If an updated FIRM indicates that an elevated property now faces a higher risk of flooding—say, a property that was initially mapped as being 4 feet above BFE but is reappraised as being just 1 foot above BFE—the property owner can continue to pay the previous, lower-risk premium. As of September 2018, about 9 percent of NFIP policies received cross subsidies from one of those two forms of grandfathering.34

Step Forward, Step Back

In 2012, lawmakers took a big step toward curtailing NFIP subsidies by enacting the Biggert–Waters Flood Reform Act. Under the legislation, premiums for non-primary residences, severe repetitive loss properties, and business properties (about 5 percent of policies) were to increase 25 percent per year until they reflected the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s best estimate of their flood risk.35 Pre-FIRM single-family homes had to have elevation certificates indicating BFE levels to ensure proper pricing because rates vary with the elevation of the structure above BFE. Grandfathering of structures from zone and elevation reclassification was to be phased out through premium increases of 20 percent per year until the actuarial fair prices were reached.36 Finally, the sale of any grandfathered properties would subject the new owner to actuarially fair rates for coverage.

But after Hurricane Sandy hit New Jersey and New York later in 2012, and FEMA subsequently released new flood maps indicating increased risk, thousands of homeowners were faced with large premium increases.37 Congress retreated from the Biggert–Waters reforms when it enacted the 2014 Homeowners Flood Insurance Affordability Act (HFIAA).38 The NFIP’s original grandfathering provisions were reinstated. The assessing of actuarial levels upon sale of a property was repealed.39 And most properties newly mapped into a 100-year floodplain after April 1, 2015 receive initially subsidized premiums for one year, though they then increase 15 percent per year until they are actuarially fair. As of September 2018, about 4 percent of NFIP policies receive this last form of subsidy.40

How much do the NFIP subsidies reduce premiums? In 2011, FEMA estimated that policyholders with discounted premiums were paying roughly 40–45 percent of the full-risk price.41 Later in the decade, the Congressional Budget Office estimated “that the receipts available to pay claims represent 60 percent of expected claims on the discounted policies.”42

Private Flood Insurance

Despite the general lack of private flood insurance since the 1927 Great Mississippi Flood, some private insurance does exist in practice, primarily for commercial and secondary coverage above NFIP limits.43 The 2012 Biggert–Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act directed FEMA to allow private insurance coverage that was equivalent to NFIP coverage to qualify as complying with the requirement that homes have flood insurance if they are located in flood zones and have federally sponsored mortgages.44 The agency took seven years, until July 2019, to write the regulations implementing the statute. Under pressure from Congress, FEMA also removed language from contracts with the private insurers that wrote federal NFIP policies that prohibited them from offering other flood-insurance products.45

Arbitraging NFIP’s Cross Subsidies

An important reason that private insurers are interested in offering flood insurance is the cross subsidies within the federal program. Originally, the subsidies for pre-FIRM structures were to come from taxpayers explicitly through appropriations, but that system was abandoned and replaced with cross subsidies from new structures to old—that is, post-FIRM structure owners paid a de facto “tax” as part of their premiums to cover pre-FIRM structures.46 And, as described earlier, some newer structures that undergo A to V zone or BFE transitions are also cross subsidized.

Private insurance allows those who would be overcharged in the federal program to escape from paying this “tax.” A modeling exercise that examined premiums for single-family homes in Louisiana, Florida, and Texas suggested that 77 percent of single-family homes in Florida, 69 percent in Louisiana, and 92 percent in Texas would pay less with a private policy than with the NFIP; however, 14 percent in Florida, 21 percent in Louisiana, and 5 percent in Texas would pay over twice as much.47

Cross subsidies work only if entry is restricted, forcing people to pay the “tax.”48 The most famous U.S. example of this is telephone cross subsidies from long distance to local service back in the days of the AT&T monopoly. Long-distance rates were set far above cost to keep local calling prices below cost. The entry of MCI into long-distance service allowed callers to escape this tax, ultimately yielding the breakup of AT&T and the end of the cross subsidy.49 The decision by Congress to expose federal flood insurance to private alternatives likewise reveals and eventually should eliminate the cross subsidies.

FEMA has responded to private flood insurance with proposed revisions to its premium schedule to price the risk of its individual policies more accurately. Currently, NFIP rates are not finely tuned, meaning they only roughly reflect the risk posed by a particular property. They vary only by zone (A or V) within the SFHA and with structure elevation above the BFE.

As the CRS explains in a 2021 report:

For example, two properties that are rated as the same NFIP risk (e.g., both are one-story, single-family dwellings with no basement, in the same flood zone, and elevated the same number of feet above the BFE), are charged the same rate per $100 of insurance, although they may be located in different states with differing flood histories or rest on different topography, such as a shallow floodplain as opposed to a steep river valley. In addition, two properties in the same flood zone are charged the same rate, regardless of their location within the zone.50

In contrast, “NFIP premiums calculated under [a proposed new risk assessment formula] Risk Rating 2.0 will reflect an individual property’s flood risk” using historical flood data as well as commercial catastrophe models.51 Risk Rating 2.0 took effect on October 1, 2021, for new NFIP policies and on april1, 2022 for existing NFIP policyholders.52

So, some proportion of private retail flood insurance in the United States is the result of cross subsidies within the current FEMA system. Once those subsidies are eliminated by private competition, FEMA policies allegedly will consist only of explicitly subsidized policies, which will be of no interest to private insurers, and the more-or-less actuarily fair policies that private insurers presumably could takeover.

The Economics of Subsidies

If cross subsidies within the NFIP are eliminated either through competition from private provision or explicit change in the statute by Congress, and Congress chooses to explicitly subsidize some residential structures through appropriations, how should it design subsidies?

One possibility is to limit the subsidies to those with limited income or wealth. In the typical means tested program, benefits (subsidies) are given to recipients whose income or wealth falls below a threshold set by Congress. Economists dislike such program design because benefits fall to zero if the threshold is exceeded; the threshold acts analogously to a confiscatory tax.

Alternative designs reduce subsidies gradually as income or wealth increases. Such designs reduce the gaming of the subsidy system through which recipients get full benefits as long as their market income remains just under the threshold. In the alternative designs, subsidies are reduced by some steady amount for every dollar increase in income or wealth. The lower the benefit-reduction rate the better the incentives to increase market income through work, but the total budget for transfers increases.

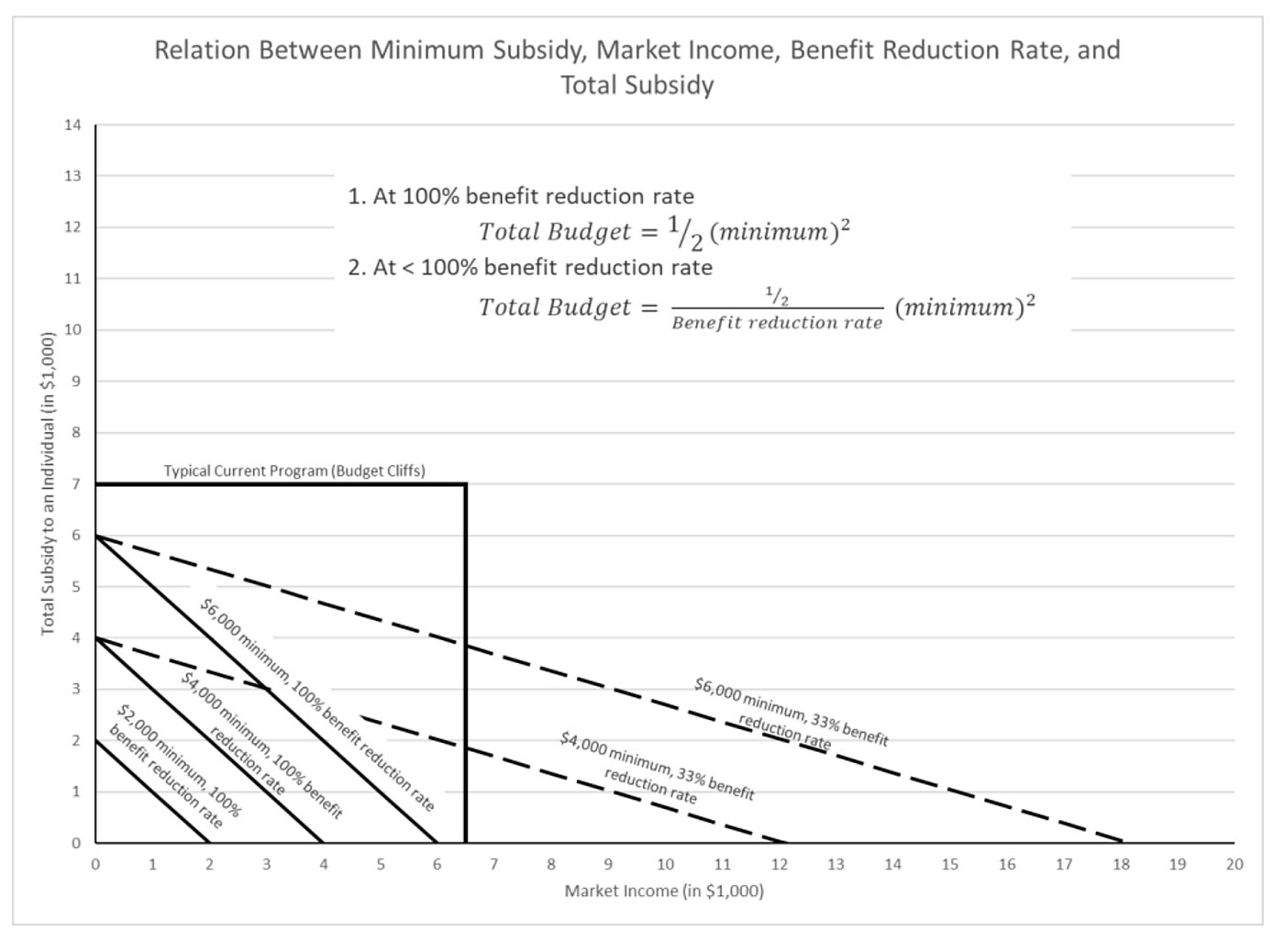

These tradeoffs are illustrated in the following figure. The subsidy amounts are listed along the y axis. The market income of the recipient is along the x axis. And the total expenditure for subsidies is indicated by the area within the rectangle or triangles in the figure. There are three variables in the policy design: the subsidy amount for those with the lowest resources (the intercept in the figure along the y axis where market income is zero), the rate at which subsidies decline as income increases (the slope of the rectangle or triangle in the figure), and the total expenditures on subsidies (the area within the rectangle and various triangles).

The Congress may pick any two of the three, but once it does, the value of the third variable logically follows. Liberals often want a high minimum. Conservatives often want a smaller budget. The result is either a budget cliff or a very high benefit-reduction rate. The result is very poor incentives for those receiving subsidies to improve their market income. A more incentive-compatible design would have a low benefit reduction rate with respect to income, but two politically difficult results follow: a larger budget for subsidies and small non-zero subsidies for those who are not poor.

Recommendations for Congress

Federal flood insurance arose as a policy device with two purposes: to reduce the use of post-disaster congressional appropriations for disaster relief and to impose the cost of rebuilding on the owners through premiums. The Congress should recommit to those goals.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify before you and share my research on this important topic. I look forward to your questions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.