Introduction

Chairman Paul, Ranking Member Peters, and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify at today’s hearing. My name is Norbert Michel, and I am Vice President and Director for the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute. The views I express in this testimony are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of the Cato Institute.

In 2008, as part of its response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve purchased large quantities of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. These purchases, and the corresponding dramatic increase in the Fed’s balance sheet, were highly controversial, with many people fearing the Fed’s actions would rapidly lead to higher inflation. However, the Fed managed to keep inflation in check after those purchases created enormous quantities of excess reserves by implementing a new operating framework, one where it began paying interest on banks’ excess reserves.

This operating framework, which received much less attention than the Fed’s asset purchases themselves, effectively divorces the Fed’s monetary policy stance from the size of its balance sheet. In other words, unlike under its previous operating framework, the Fed’s asset purchases, which increase bank reserves, could no longer automatically be associated with expansionary monetary policy (or its natural effect, inflation).

Traditional Monetary Policy Framework

A central bank exercises monetary controlby regulating the economy’s overall liquidity (the availability of cash or cash-like assets) to indirectly influence the economy’s general course of spending, prices, and employment. Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed exercised monetary control mainly through open market operations, that is, the buying and selling of short-term Treasury securities on the open market.1

The Fed conducted these operations with the specific intent of increasing or decreasing the quantity of reserves—a highly liquid asset—in the banking system, thereby increasing or decreasing the amount of money that banks could lend. This system worked because banks need reserves to make new loans, and only the Fed can increase (or decrease) the total amount of reserves in the banking system.

Under this traditional framework, when the Fed wanted banks to create less money, it took reserves out of the banking system by selling the Fed’s own securities. These sales reduced the aggregate amount of money that banks could create because it caused banks to use reserves for buying securities from the Fed rather than for funding additional private loans. Conversely, when the Fed purchased securities on the open market it increased reserves in the system, thus enabling banks to create more money with new loans. When an individual bank did not have enough reserves to make more loans (create more deposits or currency), it would simply borrow those reserves from another bank. Thus, while the Federal Reserve decided the total amount of reserves in the banking system, private banks ultimately determined how those reserves were allocated throughout the system.

Traditionally, banks commonly lent and borrowed reserves to satisfy their legal (and precautionary) requirements. This activity took place in the federal funds market, so named because banks hold reserve balances at the Federal Reserve. Traditionally, the interest rate in this lending market, the federal funds rate (FFR), was a market-determined rate. In other words, private banks’ lending negotiations—not the Federal Reserve—determined the FFR. While the Federal Reserve did not set the FFR itself, it did set a target for the FFR based on ensuring that overall liquidity was consistent with its broader macroeconomic goals. The Fed then conducted its open-market operations to ensure that the FFR stayed near the desired target.

Influencing Rates vs. Setting Rates.

The Fed did not set the FFR, but the Fed’s open market operations typically had a great deal of influence on the FFR—especially over short intervals—because the Fed is the monopoly supplier of bank reserves. While the Fed determines the total quantity of reserves in the banking system, market forces (banks’ decisions based on their individual reserve needs) determined the distribution of reserves within the system in the traditional framework. This process allowed the Fed to rely on banks’ demand for reserves as a decent indicator of the demand for money (or, more generally, liquidity). The aggregate demand for reserves, in conjunction with the total supply, ultimately determined the FFR.

By adjusting the supply of reserves in the system “just enough” to meet the demand for reserves at its chosen target, the Fed was (in theory) able to offset changes in demand without disrupting market forces. In such a system, the target FFR is merely a means to an end—it is a policy instrument but it is not a policy objective.

This policy framework depends on the Fed keeping a minimal footprint in the market for reserves, causing some economists to refer to the traditional framework as a reserve-scarcity regime. All else constant, a scarcity of reserve balances (relative to demand for reserves) results in a larger volume of reserve lending between banks. In such an operating environment, the FFR conveys information based largely on conditions in private credit markets, as perceived by the private lenders and borrowers putting their capital at risk.

On the other hand, the Fed’s open market operations would have very little influence on the federal funds market if reserves were more attractive (on a regular basis) than other uses of funds. In such an environment, with plentiful reserves that have little opportunity cost, banks would find it unnecessary to borrow reserves and the FFR would no longer be the result of the same market process. In fact, the enormous buildup in reserves during the 2008 crisis ultimately caused interbank lending markets to break down and contributed to the Fed abandoning its traditional operating procedures. As a result of switching to the new operating procedures, daily trading volume in the fed funds market fell from its pre-2008 level of $150–$175 billion to just $60–$80 billion in the mid-2010s.2

Post-2008 Monetary Policy Framework

As the 2008 crisis unfolded and the Fed engaged in more emergency lending, the Fed found it difficult to meet its overall macroeconomic goals and maintain what control it had over the FFR. While trying to keep inflation under control required tighter monetary conditions, providing emergency liquidity to the financial system required looser monetary conditions. To resolve these policy conflicts and allow further emergency liquidity provisioning, the Fed changed its operating framework by moving to a system that depends on making interest payments on reserves.

Economists have long recognized that requiring banks to hold non-interest-bearing reserves acts as a tax on bank deposits and, therefore, on bank depositors.3 However, the Fed

asked Congress for this authority for reasons that went well beyond merely offsetting the cost of reserve requirements. In his memoir, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke explained the request as follows:

We had initially asked to pay interest on reserves for technical reasons. But in 2008, we needed the authority to solve an increasingly serious problem: the risk that our emergency lending, which had the side effect of increasing bank reserves, would lead short-term interest rates to fall below our federal funds target and thereby cause us to lose control of monetary policy. When banks have lots of reserves, they have less need to borrow from each other, which pushes down the interest rate on that borrowing—the federal funds rate.

Until this point we had been selling Treasury securities we owned to offset the effect of our lending on reserves (the process called sterilization). But as our lending increased, that stopgap response would at some point no longer be possible because we would run out of Treasuries to sell. At that point, without legislative action, we would be forced to either limit the size of our interventions… or lose the ability to control the federal funds rate, the main instrument of monetary policy.

So, by setting the interest rate we paid on reserves high enough, we could prevent the federal funds rate from falling too low, no matter how much lending we did.4(Emphasis added.)

As this passage demonstrates, Fed officials believed that paying interest on reserves would help the Fed hit its interest rate target, and that the rate they paid on reserves would serve as a floor for the FFR. Their intent had been to create a corridor system, whereby the interest rate on reserves would be set below the target FFR. However, the Fed did not successfully create a corridor system due to its conflicting goals.

The Fed wanted to pay interest on excess reserves so that banks would hold their excess reserves at the Fed rather than lend them in the federal funds market. The only possible way to accomplish this task, of course, was to offer banks a higher rate of interest on excess reserves than they could earn by lending those reserves in the federal funds market. Thus, the rate it paid on these reserves could not serve as a floor for the FFR and sterilize the Fed’s asset purchase/emergency lending operations.

The Fed’s flooding of the banking system with reserves in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis necessitated reliance on the interest on reserve (IOR) program because the Fed lacked an alternative way to dissuade banks from using those reserves to create new loans and deposits. In this new “abundant reserve” framework, changing the quantity of these reserves no longer affects the FFR, so normal open market operations—the buying and selling of Treasury securities—became an ineffective tool for implementing monetary policy. However, the IOR should still be effective at changing the interbank lending rate because banks generally will not lend to other banks at rates lower than the risk-free rate at which they can collect interest from the Fed. Consequently, changing the IOR rate to affect the cost of holding reserves is now the Fed’s main instrument for changing the FFR and thereby conducting monetary policy.

Complications of the New Framework

The Fed’s IOR program has been a controversial inclusion to US monetary policy. While the program received little attention from critics prior to the COVID-19 crisis, that inattention is largely due to interest rates being at historic lows.5 That is, because the US remained in a period of historically low interest rates, the Fed’s interest payments through the IOR program were relatively small. However, because interest rates rose in response to the post-pandemic surge in inflation, the Fed has disbursed billions in risk-free government payments to large banks. These losses, of course, have brought unfavorable political attention to the program.6

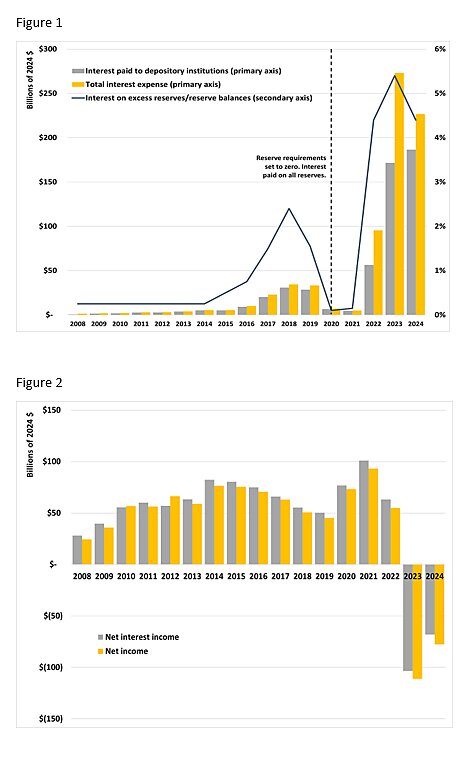

As Figure 1 shows, the Fed’s interest payments (adjusted for inflation to 2024 dollars) have increased dramatically.7 Moreover, the rate of increase in interest expenses closely mirrors the rate of increase in the rate the Fed pays out on the reserves (the “IOR” rate). This latter fact was not true in the late 2010s when the Fed raised the IOR but kept interest payments in check because it only paid interest on excess reserves as opposed to on all reserves, a policy it changed during the pandemic.

As Figure 2 shows, these large interest expenses resulted in the Fed’s only recorded losses since 2008 and the only losses on record since the data became available. The Fed has mostly hand-waved these losses away and used financial gimmickry to label them “deferred assets” that they have promised to balance with future profits.8

One obvious problem with these current events is that there is no guarantee interest rates will come down to their pre-pandemic levels, reducing the Fed’s interest burden and allowing its financials to turn back to profit rather than loss. Even if the Fed manages to turn a profit, taxpayers are unlikely to reap those benefits. It will likely take years of future profits to offset the nearly $200 billion the Fed has already lost in the past two years alone—profits that would usually go to the Treasury to help relieve some of our massive fiscal deficit.

Regardless of the future path of interest rates, the IOR program provides billions of government dollars to large financial institutions as risk-free interest, essentially giving banks a massive government handout. The average American, though, earns close to nothing on their own savings accounts at these same institutions.

Moreover, the IOR program leaves banks with little incentive to borrow from each other or lend funds to the public, resulting in significantly lowered activity in the federal funds market.9 One consequence of this inactivity has been a dampening of the effects of the FFR on other borrowing costs.10 At the same time, inflation went far beyond the Fed’s 2 percent target, ultimately requiring the Fed to severely tighten its monetary policy stance. By late 2023, the Fed had increased the FFR by raising the IOR rate to 5.40 percent. The consequence of this post-pandemic policymaking was a dramatic increase in both the principal and interest rate of the Fed’s liabilities.

Fed officials are largely unconcerned about losses from interest payments or the deferred assets they create to offset these losses. According to a press release: “A deferred asset has no implications for the Federal Reserve’s conduct of monetary policy or its ability to meet its financial obligations.”11

It is technically true that the Fed can continue to exhibit losses, as it does not require operational profitability like a private financial firm does, but this view is unwarranted. Indeed, if the Fed were a private bank, any one year of such losses may have been enough to shutter its business. Still, while the Fed is not a private bank and it can sustain these losses for a longer period, it is not true that there are no causes for concern due to these losses and the IOR framework. The following list provides four major reasons for concern over the IOR framework and the resulting Fed losses.

- The economic costs of these losses are high. Assuming that marking off future profits to account for current losses has no economic effects is economically unsound. Balancing books via accounting rules ignores opportunity costs. That is, accounting rules do not quantify the gains that could have been achieved from using funds for alternative purposes, such as paying down federal debt. In fact, for decades profits from the Fed’s operations have been remitted to the Treasury and gone toward paying off the federal government’s massive fiscal deficit. Now, the Treasury will have to issue even more debt, which will lead to an even greater fiscal imbalance. In other words, these higher interest payments will place a higher burden on future taxpayers even though the Fed’s accounting costs appear to be zero.

- The IOR framework creates a conflict of interest with the Fed’s mandate to stabilize prices. The Fed’s primary mechanism for achieving stable prices is to influence the FFR by altering the IOR. Specifically, to combat inflation, the Fed tightens its monetary policy stance by raising the IOR. However, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, increases in the IOR result in large interest expenses and consequently losses for the Fed. Despite what they may claim publicly, Fed officials cannot continue to exhibit losses on their financial statements indefinitely. Realistically, at some point, large financial losses would undermine the Fed’s ability to support the banking sector and the US government’s ability to issue new debt, just as it would in politically unstable countries. Moreover, losses create a potential complication for monetary policy because the Fed must increase the IOR to combat inflation even though every increase in the IOR rate increases the Fed’s potential losses.12 This inherent conflict only makes the Fed’s fight against inflation more difficult.

- The IOR system facilitates government support for the private financial sector. At its core, the IOR policy is a government subsidy to large financial institutions. Banks now have their own risk-free savings accounts, giving them returns that are hundreds of basis points higher than what regular consumers receive on their own deposits at the very same institutions (the current rate is 3.9 percent).13 Moreover, the billions that banks receive in interest payments have reduced their incentive to lend in the private market, reducing the cash available to regular Americans to borrow while flooding the banking system with trillions in reserves.

- More accessible money spigot. The IOR framework divorces the Fed’s monetary policy stance from the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. It is designed to allow the Fed to purchase as many assets as it would like, all while paying firms to hold on to the excess cash that these purchases create. This framework can all too easily allow the Fed to be a pawn of the Treasury, enabling the government to run larger deficits. It also opens new opportunities for political groups to pressure the Fed for direct funding.

Winding Up the IOR Program

In the wake of the 2008 crisis, the Federal Reserve made trillions of dollars in emergency loans and expanded its balance sheet by purchasing large quantities of long-term Treasuries and MBS. These operations gave rise to an experimental policy framework that replaces traditional market activity with bureaucratically administered interest rates. To normalize monetary policy and restore the market forces that the Fed has displaced, the Fed must shrink its balance sheet and end the IOR program.

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed’s balance sheet held less than $1 trillion in securities, and its total assets rarely exceeded 10 percent of the commercial banking sector’s total assets. After the financial crisis, this share has regularly exceeded 20 percent, with asset purchases during the pandemic increasing the share to 40 percent (and inflating the balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion at its peak in 2022). Since 2022, the share has fallen to 28 percent, and the Fed now holds approximately $6.5 trillion in assets.

Many point to the dangers of rapidly shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet and ending the IOR program, and they are right to be concerned.14 An immediate end to the IOR program would result in banks rapidly lending those reserves to the public. Such a sudden and large outflow of cash from banks into the wider economy could cause high inflation. But a careful approach that winds down the size of banks’ balance sheets over time would allow the repeal of IOR while also ensuring consumers don’t suffer another bout of severe inflation.

Congress should require the Fed to implement a plan that shrinks the balance sheet in no more than 15 years, approximately the same amount of time it took to enlarge the balance sheet since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The goal should be to reduce the Fed’s holdings to no more than the pre-2008 share of the commercial banking sector. Congress should also limit the size of the Fed’s balance sheet by, for example, capping the Fed’s total assets at no more than 10 percent of the commercial banking sector’s total assets, the approximate share held by the Fed prior to the 2008 financial crisis.

Naturally, these changes would come with an implicit promise to end quantitative easing as a monetary policy tool. At that time, the Fed’s authority to pay interest on reserves should be repealed. In this scenario, bank reserves would once again be scarce, and the system would revert to an interest rate corridor with the FFR divorced from the value of the IOR. Consequently, eliminating IOR would be minimally economically disruptive.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.