Introduction

Chairman Hill, Ranking Member Waters, and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify at today’s hearing. My name is Norbert Michel and I am Vice President and Director for the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute. The views I express in this testimony are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of the Cato Institute.

Good monetary policy helps American workers, retirees, and savers by ensuring that the economy does not stall due to an insufficient supply of money. It also ensures that the economy does not overheat due to an excessive supply of money. To accomplish this task, the Federal Reserve needs to supply the amount of base money the economy needs to keep moving. It needs to do so in a neutral fashion, rather than allocate credit to preferred sectors of the economy. This operating standard dictates that the Fed maintains a minimal footprint in the market so that it does not create moral hazard problems, crowd out private credit and investment, or transfer financial risks to taxpayers. Finally, the Federal Reserve should conduct monetary policy in a transparent manner, with maximum accountability to the public through their elected representatives. Through much of its history, and particularly since the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has failed on all these measures, culminating in abnormally high and prolonged inflation following the COVID-19 pandemic.

A central bank’s policy failures are particularly damaging because money is the means of payment for all goods and services. The Fed’s misguided policies have long distorted prices and interest rates, thus causing people to misallocate resources in ways that have exacerbated business cycles. The Fed’s regulatory failures have also led to resource misallocation and increased moral hazard, a most unfortunate outcome given that a central bank does not need to be a regulator to conduct monetary policy. Aside from these regulatory failures’ contribution to the 2008 crisis, the Fed’s monetary tools have grown and morphed beyond the simple and standard way it conducted monetary policy during the Great Moderation. The Fed has essentially been paying large financial institutions to refrain from lending to Main Street businesses by paying them risk-free interest to sit on cash. The Fed has been able to conduct these experimental monetary policies largely because Congress has given the Fed so much policy discretion. To correct these problems, Congress must first recognize that the Federal Reserve is not an indispensable part of the economy.

Too many policymakers view the Fed as a temple of scientists who know exactly which dials to turn to speed up or slow down the economy at precisely the right time, even though there is more than enough evidence to question this idea. These facts, along with the Fed’s long-term track record, should put to rest the notion that the central bank can fine-tune the economy. Congress has an obligation to oversee the Fed, and the Fed has not, even according to its own projections, delivered on its economic promises. Congress should hold the Fed accountable and ensure that it no longer has the discretion to “manage” the economy however it sees fit through some vague macroeconomic mandate.

Understanding Monetary Policy

When considering the tools the Fed has at its disposal, it seems unreasonable to expect the Fed to achieve economic fine tuning. The Fed’s main tool is buying (or selling) government securities to increase (or decrease) the monetary base—it conducts these operations to influence the federal funds rate (FFR) towards a predetermined target. Since the FFR is the cost at which banks can raise liquid money themselves, it in turn affects the various rates at which banks are willing to lend to consumers and other economic agents. At least, this is how monetary policy is supposed to work.

Note that even when the Fed buys securities to increase reserves in the banking system, private banks still have to make loans to result in increased economic activity. Likewise, if the Fed increases its target rate and sells securities to make reserves scarcer, private banks have to decrease their lending to slow economic growth. In either instance, there is no guarantee that the Fed’s operations will lead to a precise change in lending that will lead, in turn, to a precise change in the broader money supply, interest rates, prices, unemployment, or overall economic activity.

Post-Pandemic Fed Failure

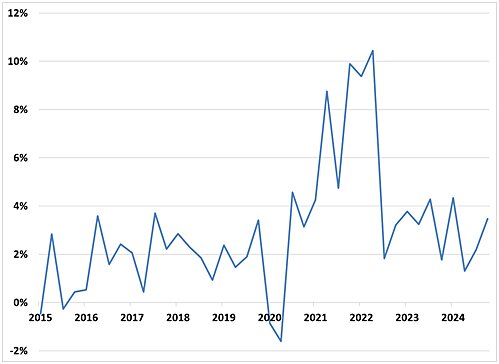

The Fed’s inability to control the economy was apparent when it failed at its primary responsibility to keep prices stable in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 1 shows the annualized quarterly CPI-based inflation rate in the U.S. over the past ten years. As the graph shows, inflation was significantly higher, exceeding 10% in 2022, than the Fed’s 2% target through much of the immediate aftermath of Covid. It is true that excessive fiscal spending and severe supply shocks made the Fed’s price stability mandate difficult to achieve but nonetheless the Fed exacerbated rather than curtailed inflationary pressure—primarily by discarding objective policymaking.1 Economic evidence routinely demonstrates that the Fed performs better when following a policy rule.2 Despite this evidence, the Fed had been getting increasingly discretionarily ever since the financial crisis.3 The Fed doubled down on subjective monetary policy during its disastrous 2020 framework review that increased the vagueness of its policy goals. For instance, the FOMC adopted “flexible average inflation targeting” (or FAIT) during the review—under this method, the Fed would target inflation to be 2 percent on average over an undefined period. Post-pandemic inflation was a direct and predictable consequence of increased Fed discretion.

Figure 1: Annualized Consumer Price Index Inflation in the U.S., Quarterly

Fixing Monetary Policy with a Rule

While money supply changes do not affect the “real” level of economic activity in the long run, they can still affect real outcomes in the short run. Consequently, many economists have long sought ways to use monetary policy to minimize short run economic disruptions (often called “business cycles”). Of course, the main tool for the Fed to try to minimize these economic disruptions is influencing short-term credit markets by targeting a value for the federal funds rate.

For decades, many have argued for various monetary policy rules to help achieve this goal. Some, for instance, have argued that the monetary base should be frozen, with private banks creating currencies to fill the demand for money. Others have called for constant growth of the monetary base at a given percentage each year. Many modern macroeconomists advocate for rules that directly determine the target for the FFR rather than rules that govern the growth of the money supply. These rules generally update the target rate in response to current values of macro indicators such as inflation, unemployment, or output growth.

Many central bankers argue that these kinds of monetary rules are too restrictive, and that they would prevent the Fed from enacting the appropriate monetary policy response to the economic changes they face. Instead, they advocate for maintaining a high level of discretion to implement monetary policy as they see fit because of the enormous complexity of the economy and its ever-changing nature. But the nature of the economy makes the case for rules-based policy. Since no one person (or small group of central bankers) can be expected to understand and react properly or consistently to changing economic conditions, policy rules would reduce uncertainty among citizens and firms by making the Fed more predictable and transparent. Committing to a rule would also prevent the Fed from raising or lowering rates out of undue political pressure and, therefore, better insulate its policy independence.

Debates over which specific rule the Fed should adopt are useful but ultimately should not stand in the way of committing to a rule in the first place. Most monetary policy rules take the form of an interest rate feedback system where the Fed sets the target for the FFR in response to current values of key macroeconomic indicators. Since the economy is interlinked and most macroeconomic indicators mirror each other, the general recommendations the various rules offer should (theoretically) be similar. Indeed, this is borne out by the data.

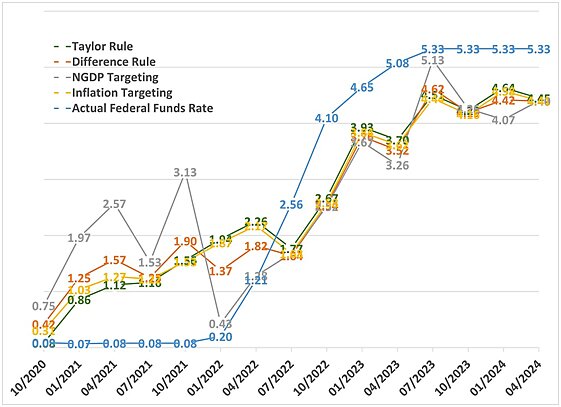

Figure 2 below compares the actual FFR to its hypothetical counterparts under various monetary policy rules. The rules considered are popular choices from academia or policy analysts and include: the Taylor rule, a difference rule, NGDP targeting, and pure inflation targeting.4 As Figure 2 shows, policy recommendations across the various rules closely align. (NGDP targeting is slightly more volatile than the other rules.) The key observation is that any of these policy rules would have helped the Fed avoid its costly post-pandemic mistakes. All rules recommended raising the FFR well before the Fed did so in early 2022. Instead, discretionary monetary policy led the Fed to incorrectly label inflation as “transitory” and its sluggishness in tightening its stance likely allowed inflation to become entrenched. Once it realized its mistake, the Fed had to execute a series of rapid rate hikes and has since kept its rate target higher than all the rules recommend. Had the Fed followed such a rule, it is likely that Americans may have experienced a stable increase in rates and avoided suffering the highest bout of inflation in at least 40 years.5

Figure 2: Comparing the Fed Funds Rate Target to Rules-Based Alternatives

Still, we should not expect the Fed to successfully manage the economy by consistently reaching precise macroeconomic goals. A central bank is ill-suited to this sort of management of the economy. Instead, Congress should require the Fed to adopt a rules-based monetary policy to reduce uncertainty by anchoring people’s expectations regarding what the Fed will do on an ongoing basis. A template for such policy already exists—the Fed Oversight Reform and Modernization (FORM) Act of 2015. Under legislation such as the FORM Act, the Fed would be required to specify and follow a rule when setting its interest rate target. The choice of which rule is up to the Fed, and the rule is binding only in that once the Fed picks a rule it must follow the rule unless it explains deviations from the rule to Congress.

The Fed Should Revise its Inflation Target

The Fed measures the success of its price stability mandate against a 2 percent inflation target. Aside from the fact that the Fed has on average, overshot its target throughout the post-World War II period, if the Fed keeps annual inflation at 2 percent or above, US consumers will never realize the benefits of long-term productivity growth. The reasons the Fed has used to justify a constantly positive rate of inflation—it greases the wheels of the economy, it prevents workers from suffering wage declines, it shields the economy from deflation, etc.—are not empirically founded or based in sound economic theory.

As products become more efficient to produce through permanent technology improvements (such as major computer chip improvements or AI automation), goods become cheaper to produce and consequently result in cheaper prices for consumers. As a result, long-term price level changes are inextricably linked to long-term productivity. Along with reviewing its current rule choice, Congress should also require the Fed to review data on productivity trends and adjust its inflation target accordingly. One benefit of a pre-announced inflation target (2 percent or otherwise) is that it helps cement inflation expectations. Consequently, if an adjustment is made to the inflation target, the new choice should be clearly communicated to U.S. firms and consumers to ensure an adequate adjustment to their inflation expectations.

The Fed Should Not Engage in Credit Allocation

In December 2008, the Fed began quantitative easing (QE), large-scale asset purchasing programs whereby the Fed purchased long-term Treasuries and the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac that were (at that time) held by private financial institutions. By the end of 2014, the Fed had expanded its balance sheet by purchasing approximately $2 trillion of long-term Treasuries and MBS, respectively. The Fed took its balance sheet from less than $1 trillion to nearly $4.5 trillion. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a fresh round of QE raising the Fed’s balance sheet to a current value of $6.8 trillion – roughly one-third the size of the U.S. commercial banking sector.

These purchases, ostensibly, were designed to inject liquidity into the banking system, thus preventing a collapse in bank lending and a simultaneous collapse in the economy. However, as these purchases created excess reserves in the banking system, the Fed chose to pay above-market interest rates on these excess reserves. As a result, instead of creating new money through additional lending and preventing (or lessening the severity of) a recession, the Fed’s QE policies expanded only the amount of excess reserves in the banking system. Banks mostly held onto the cash that the Fed gave them when it executed all those securities purchases, so it is rather difficult to argue that these Fed policies did much of anything to expand the economy or prevent a macroeconomic collapse. According to press releases, the Fed paid interest expenses of $6.9 billion to banks in 2015, an amount that increased to $281.1 billion in 2023.6 Consequently, the Fed reported operating losses of $114.3 billion in 2023.

Interest payments to financial institutions aside, the initial QE policies allocated credit to the housing and government sectors through purchases of Treasuries and MBS, respectively. At the very least, the Fed’s actions have distorted prices in the housing market as well as the broader financial markets. Because an increase in demand for Treasuries, all else constant, puts upward pressure on their price, it also puts downward pressure on their interest rates. Thus, the Fed’s policies, which increased the demand for low-risk financial assets, certainly contributed to the low-interest-rate environment experienced in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Individuals with low-risk asset preferences, therefore, suffered lower returns than normal partly because of the Fed’s policies.

This balance sheet expansion by the Fed diverted hundreds of billions of dollars in credit from the private sector to the federal government,7 a twofold problem because the private sector allocates credit more efficiently than the government8 and because it does so without directly placing taxpayers at risk for financial losses.9 Aside from distorting interest rates in credit markets, these policies did not make housing prices more affordable.10

These policies exemplify why a neutral central bank is desirable. For a central bank to remain neutral, it must keep a minimal footprint in the private sector. A central bank that, for instance, purchases nearly one-third of an asset class, as the Fed did with Treasury securities following the financial crisis, cannot remain neutral. There is a fundamental speculative nature to all financial activity, a fact that further dictates that government agencies, including central banks, should undertake as little market activity as possible to maintain liquidity in the banking system. Although the Fed has episodically adhered to providing only system-wide liquidity, the Fed’s lending policies have gone against such a sound prescription for the bulk of its history. In fact, judged against the classic prescription for a lender of last resort (LLR), the Fed’s long-term track record is rather poor. Its LLR policies have frequently jeopardized its operational independence and put taxpayers at risk.11

During the 2008 financial crisis the Fed allocated credit directly to a select few firms and officially allocated credit to specific firms through several broader lending programs. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates that from December 1, 2007, through July 21, 2010, the Federal Reserve lent financial firms more than $16 trillion through its Broad-Based Emergency Programs.12 To put this figure in perspective: Annual gross domestic product (GDP) reached $16.8 trillion in 2013, an all-time high for the U.S. at that time. During the crisis, the Fed created more than a dozen special lending programs by invoking its emergency authority under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Separately, Bloomberg Markets magazine estimates that the Fed’s total emergency loans from 2007 to 2010 charged $13 billion below market rates.13

Charging below market rates to select firms, on suspect collateral, is the exact opposite of the classic LLR prescription. The goal should be to lend widely, as safely as possible, at high rates so that firms have every incentive to stop relying on the Fed for funds. Instead, the Fed effectively provided financial institutions with a source of subsidized capital for up to several years. These policies encouraged more risky behavior than would have otherwise taken place because the government accepted much of the downside risks for private firms (the well-known moral hazard problem), and they also crowded out private alternatives as the Fed essentially became a lender of first resort. Though difficult to quantify, these policies surely detracted from the number of income-producing jobs available in the private sector. Critics argue that the 2008 liquidity crisis was atypical because market participants had difficulty determining the value of various securities, thus justifying such policies, but the Fed has no advantage over anyone else in determining the market value of securities.

In response to the COVID-19 government shutdowns, the Fed again initiated multiple special lending facilities. The peak usage for the emergency lending through these facilities (from 2020 to 2021) was $222.32 billion.14 Though many of the Fed’s actions—appropriately—provided system wide liquidity, the Fed also established two facilities to support credit to large employers that went further. These facilities were the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) for new bond and loan issuances and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) for outstanding corporate bonds. Of the two, the PMCCF was the most troubling because it allowed the Fed to lend directly to commercial businesses. Ultimately, the Fed did not use this facility, but its establishment was reminiscent of the failed 1930s emergency lending programs established after the 1934 Industrial Advances Act created Section 13(b) in the Federal Reserve Act. By 1939, the district banks had provided nearly $200 million in working capital loans to nearly 3,000 applicants, and the Fed itself eventually lobbied Congress to remove the 13(b) provision, getting its wish in 1958.15

The Fed’s Failure as a Regulator

The Fed’s actions leading up to the 2008 crisis also highlight the central bank’s failure as a financial market regulator.16 The U.S. central bank has been involved in banking regulation since it was founded in 1913, and it became the regulator for all holding companies owning a member bank with the Banking Act of 1933. When bank holding companies, as well as their permissible activities, became more clearly defined under the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, the Fed was named their primary regulator. Under the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), the Fed alone approved applications to become a financial holding company—and only after certifying that both the holding company and all its subsidiary depository institutions were “well-managed and well capitalized, and … in compliance with the Community Reinvestment Act, among other requirements.”17

Although it would be unjust to place all the blame on the Fed, the fact remains that the United States experienced major bank solvency problems during the Depression era, again in the 1970s and 1980s, and during the late 2000s. At best, the Fed did not predict these crises, even though it was heavily involved (more so in the later crises) in regulating banks’ safety and soundness. In 2008, for example, Fed Chairman Bernanke testified before the Senate that “among the largest banks, the capital ratios remain good and I don’t anticipate any serious problems of that sort among the large, internationally active banks that make up a very substantial part of our banking system.”18 Simply being mistaken about banks’ capital is one thing, but the Fed played a major role in developing these capital ratios used to measure safety and soundness.

In the 1950s the Fed developed a “risk-bucket” approach to capital requirements,19 and that method became the foundation for the Basel I capital accords, which the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) adopted for U.S. commercial banks in 1988. Under these capital rules, U.S. commercial banks have been required to maintain several different capital ratios above regulatory minimums in order to be considered “well capitalized.” According to the FDIC, U.S. commercial banks exceeded these requirements by 2 to 3 percentage points, on average, for the six years leading up to the crisis.20 The Basel requirements sanctioned, via low risk weights, investing heavily in MBS that contributed to the 2008 meltdown. Furthermore, the Fed was directly responsible for the recourse rule, a 2001 change to the Basel capital requirements that applied the same low-risk weight for Fannie- and Freddie-issued MBS to highly rated private-label MBS.21

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank failed, again triggering much anger toward financial institutions and the “big” banks. Setting aside any financial missteps these banking organizations may have made, Congress should not absolve federal regulators, including the Fed, from major regulatory failures. The federal agencies released a flurry of reports on April 28. In fact, the Fed and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) both released reports on these bank failures that reveal serious shortcomings of the U.S. regulatory framework for banks. To the Fed’s credit, its report even acknowledged supervisory mistakes at the Fed leading up to SVB’s failure.22

Though any federal financial regulator could have made the very same mistakes as the Fed, a central bank does not need to be a financial regulator to conduct monetary policy. Allowing the Fed to serve as a financial regulator increases the likelihood that policy decisions will be compromised as the Fed’s employees become embedded in the financial firms they are supposed to be overseeing. The fact that Dodd–Frank imposed a nebulous financial stability mandate on the Fed only increases this possibility. Aside from these recent changes, it is completely unnecessary for the U.S. central bank to serve in a regulatory capacity, and removing the Fed from its regulatory role would leave at least five other federal regulators that oversee U.S. financial markets. The Fed is now micro-managing even more firms than it was prior to the 2008 crisis, even though it has repeatedly failed to predict, much less prevent, financial turmoil.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve has not fulfilled the long-term promise of taming business cycles, and its overall track record on inflation is not much better. These facts alone require Congress to question the Fed’s mission and role. Given that the Fed’s credit allocation policies, regulatory failures, and monetary policy mistakes—after 100 years to gain experience—worsened the most recent bout of inflation, Congress would be derelict in its duty to the American public if it allowed the Federal Reserve to continue operating under its existing ill-defined statutory mandate. It is difficult to argue that the Fed’s recent policy actions accomplished anything other than saving a favored group of creditors at the expense of all others. Providing liquidity broadly and refraining from sterilizing its operations—the opposite of what the Fed has done in its recent past—surely would have done more to benefit Main Street Americans.

Rather than hold the Federal Reserve accountable for these mistakes, policymakers appear to have put even more faith in the Fed’s ability to influence interest rates and inflation, to tame unemployment, and to ensure the safety and soundness of financial markets. Monetary policy under the current framework is clearly not working—if it were, people would have more confidence in the economy and expect lower inflation.23 To reform the nation’s monetary policy, Congress should, at the very least, take the following steps.

- Require the Federal Reserve to normalize its operations by shrinking its balance sheet, ending the payment of interest on reserves, and closing its overnight reverse repurchase facility.

- Require the Fed to implement a simple rule for its interest rate target that Congress can easily monitor and use to hold the Fed accountable. The Fed can choose its preferred rule. However, it is imperative that once Fed officials decide on a rule, they are required to either follow it or publicly explain any deviations from it.

- Require the Fed to evaluate and update its inflation target at regular intervals to account for long-term changes to productivity and technology improvements.

- Ensure that all federal policies, including those of the Federal Reserve, remain neutral with respect to whichever mediums of exchange people decide to use.

- Reduce both explicit and implicit guarantees by ending the Fed’s emergency lending authority and ending the Fed’s role as a financial regulator.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide this information, and I welcome any questions that you may have.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.