In recent years, concerns about employer concentration (the existence of only a few large employers) have increased. Employer concentration has been posited as a possible explanation for inequality, low pay, and stagnant pay growth. Antitrust authorities have been called on to consider employer concentration in merger and acquisition reviews. Concerns have been raised that employer concentration facilitates restrictions on competition, such as no-poaching agreements. And, since employer concentration can be a source of wage-setting power, concerns about high employer concentration have bolstered calls to raise minimum wages and strengthen collective bargaining.

To assess whether—or in which cases—policy should respond to employer concentration, we need to understand the nature and effects of employer concentration in the United States. In our research, we seek to answer to what extent employer concentration matters for U.S. workers’ wages and how this depends on workers’ outside job options. We estimate the effect of employer concentration on average hourly wages across more than 100,000 metropolitan U.S. labor markets over the period of 2011–2019. We use data from Burning Glass Technologies’ online job postings database to construct an employer concentration index.

While recent research has documented a negative relationship between local employer concentration and wages, the extent to which this is causal—and the magnitude of any such causal effect—is unclear. Employer concentration may be associated with other local economic conditions that also affect wages, thus complicating the estimation of any underlying wage-concentration relationship. We account for this issue using statistical methods that enable us to measure changes in local employer concentration that are not associated with local economic conditions like productivity or demand.

Assessing the effect of local employer concentration on wages and pinpointing the workers who are most affected by it requires a good definition of the relevant local labor market for workers. Using new, highly detailed occupational mobility data constructed from 16 million U.S. workers’ resumes, we show that occupational mobility is high but very different across occupations. Most current research on employer concentration does not consider the availability of job options outside of a worker’s own occupation. We account for this by developing a measure of the value of a worker’s outside job options in other occupations— an “outside-occupation option index”—and estimate its effect on wages so that we can isolate the effect of withinoccupation employer concentration.

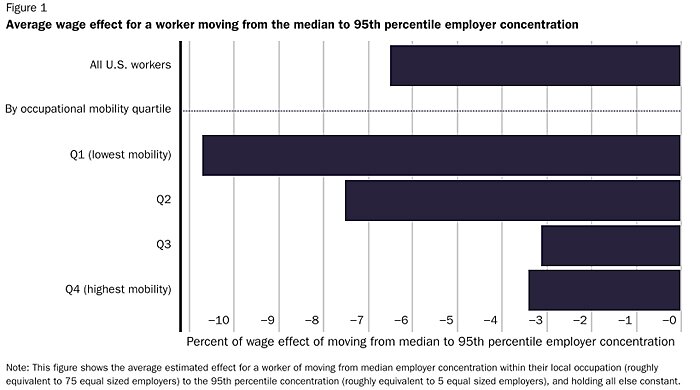

How much does employer concentration matter for wages? Our results suggest that a worker moving from the median to the 95th percentile of employer concentration results in 6.5 percent lower wages. However, the average effect of employer concentration masks important differences between occupations, as shown in Figure 1.

Within-occupation employer concentration matters much more for workers who are less able to find comparably good jobs in other occupations. For occupations in the bottom 25 percent of occupational mobility, like registered nurses and security guards, moving from the median to 95th percentile of employer concentration is associated with 10.7 percent lower wages. For occupations in the next 25 percent, we find that moving from the median to 95th percentile of employer concentration is associated with 7.5 percent lower wages. On the other hand, for occupations in the top 50 percent of occupational mobility (like counter attendants or bank tellers), moving from the median to 95th percentile of employer concentration is associated with a much smaller 3.1 to 3.4 percent lower wages.

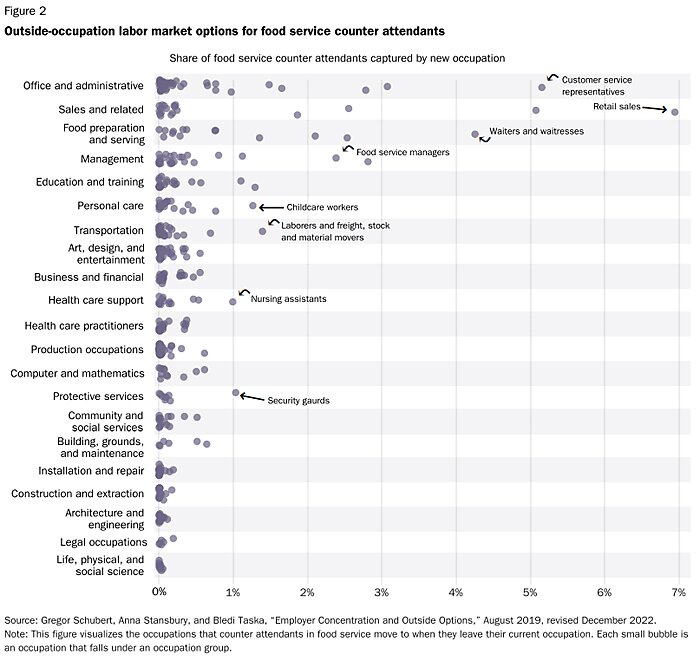

A back-of-the-envelope calculation, using our estimates, suggests that almost one-quarter of the 117 million workers covered by our data in 2019 experience wage suppression of 2 percent or more as a result of employer concentration. Many of the most affected workers are health care workers, which reflects both high health care employment concentration in a few local employers and low occupational mobility because health care workers have invested time and resources in obtaining skills specific to their occupation. How much do outside-occupation options matter for wages? We find a large positive effect of an increase in the value of outside-occupation options. A 1 percentage point ncrease in the wage of outside option occupations leads to a roughly 0.1 percent higher wage in a worker’s own occupation. Additionally, for the median occupation, moving from the 25th to the 75th percentile value of our outsideoccupation options index across metro areas is associated with a 4.4 percent increase in wages. These magnitudes are significant relative to wage differences across metro areas: for the median occupation, moving from the 25th to the 75th percentile metro area by average wage was associated with a 20 percent higher wage in 2019. These results demonstrate that job options outside of a worker’s occupation are an important part of labor markets; indeed, for many workers their true labor market is made up not only of their occupation, but also of a large cloud of occupations in diverse industries, as visualized for counter attendants in Figure 2. Therefore, changes to these options can have a meaningful influence on a worker’s labor market outcomes.

Our findings point to a middle ground between two prominent views about the effects of employer concentration in the U.S. labor market. On the one hand, employer concentration is not a niche issue confined to a few factory towns: we find large negative effects of employer concentration on wages. Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that almost 25 percent of the U.S. private sector workforce experiences nontrivial wage effects of employer concentration. On the other hand, most workers are not in highly concentrated labor markets, and the effects of employer concentration therefore do not seem big enough to have a substantial effect on the overall wage level or degree of income inequality in the U.S. economy (although other sources of wage-setting power may still be important). The fact that employer concentration affects wages for several million American workers suggests that increased policy attention to this issue is appropriate in terms of antitrust efforts, which can reduce large employers’ wage setting power; policies to raise wages in the face of employer market power, such as minimum wages or collective bargaining; and policies to increase worker mobility to reduce the degree to which any one large employer accounts for a large share of a worker’s job options.

NOTE

This research brief is based on Gregor Schubert, Anna Stansbury, and Bledi Taska, “Employer Concentration and Outside Options,” August 2019, revised December 2022. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3599454 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3599454.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.