Many new products and innovative activities in the US economy require a greenlight from the federal government before they may be commercialized. Uncle Sam’s gatekeeper role has astonishing reach, encompassing the clearance of food additives, prescription drugs, medical devices, pesticides, radiation-emitting devices, engines, fuels, firearms, deep-well injection, carbon capture and storage, ocean floor sea mining, and electronic and digital devices. Some regulatory advocates want to create new gatekeepers for everything from artificial intelligence to self-driving cars.

One little-known provision in the regulatory arcana is that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is not allowed to review the work of these gatekeepers. Executive Order 12866 gives OMB authority to review rules of general applicability, but decisions regarding a specific product or project are off-limits.

Gatekeepers have noble purposes: They ensure the protection of privacy, public health, safety, and environmental quality. However, the bureaucratic “sludge” created by the gatekeepers has pernicious side effects: They can delay lifesaving and green innovations, shield old technologies and practices from competitors, and often discourage investments in entrepreneurs, which makes the US economy less productive.

Donald Trump should aim to eliminate the sludge created by these federal gatekeepers. Two examples illustrate the sad state of affairs that entrepreneurs face.

Presidents Barack Obama, Trump, and Joe Biden did not agree much on policy, but they all insisted that our country needs to rapidly expand the mining and processing of critical minerals needed for national defense, clean energy, industrial innovation, and even laptop computers. There has been just one lithium mine operating in the United States in the last two decades, despite there being plenty of lithium under US soil.

Today, there are dozens of developers seeking permits—and fighting lawsuits—to start new US lithium mines, sometimes with subsidies from Uncle Sam. The gatekeepers in the bowels of the Department of Interior claim there is no sludge in the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) that oversees this permitting process, and they like to tell the public that it takes “only” 2.5 years to obtain approval for a new lithium mine on federal land. However, that does not account for the baseline environmental monitoring and species-protection analyses that must receive formal approval from bureaucrats at the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Army Corps of Engineers before the formal BLM review process begins. So, add many more years to this process.

Nor does this include the time it takes to defend a BLM permit in court, where simple lawsuits take a year in federal district court and another year at a federal appeals court. And this all assumes the gatekeepers approve the mine, but they obviously must reject at least some mines to justify their existence.

Other countries have much less sludge, including Australia, which is the top lithium producer in the world. And while Australia may be a close ally of the United States, its lithium supplies are not necessarily a suitable substitute for US supply: The Chinese own some of its biggest mines, leveraged by China’s industrial policy.

There is also the challenge of introducing new industrial chemicals into commerce. For decades, the United States was the most attractive jurisdiction to introduce them: The market is vast, at one point the governmental review process was fast (90 days or less), and the burden was on the EPA to prove that there was a legitimate safety or environmental issue.

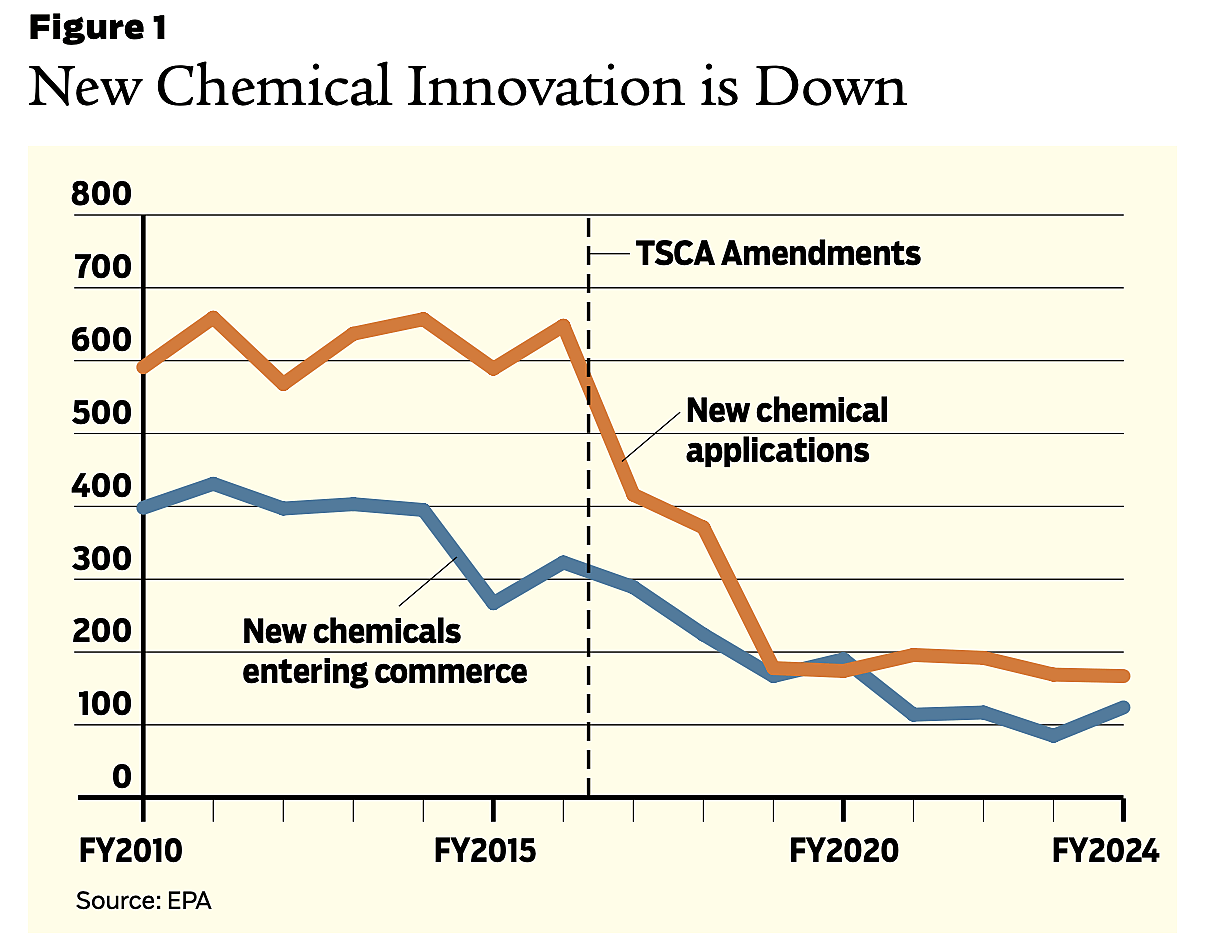

That all changed in 2016 when Congress amended the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) to require the agency to make an affirmative risk determination for every new chemical prior to manufacturing. The statute had some flexibility to be reasonable, but the Biden EPA was—to say the least—strict. Nine years later, the rate of new chemical innovation has plummeted to all-time lows, and the average EPA review time has climbed from just over 90 days to 288 days. (See Figure 1.) In some cases, EPA reviews are taking years. The longer and more uncertain review process prevents chemical innovators from meeting customer demand. Because 80 percent of industrial chemical production is sold to downstream manufacturers as inputs, the decline in chemical innovation puts all of US manufacturing at a competitive disadvantage.

President Trump can make a difference on this kind of sludge, but he cannot do it with executive orders that are high on rhetoric and deadlines (“dashboards”) without teeth. Each gatekeeper needs to be targeted with a Trump order that gets into the depths of the sludge, and OMB’s authority needs to be expanded to oversee the work of the gatekeepers. A modest start would be to clarify that OMB authority includes process efficiencies associated with agency review of products or projects.