At the Atlas Network’s most recent Freedom Forum, half a dozen foreign think tanks, mainly from the developing world, sought advice on their ongoing projects to promote free trade in their countries. Patrick Stephenson, an economist with the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, a Ghanaian think tank, told me about his country’s “Investment Promotion Center Act.” It lists certain sectors in which “an enterprise which is not wholly owned by citizen [sic] shall not invest or participate.” The prohibition covers, among other things, “the sale of goods or provision of services in a market, petty trading or hawking or selling of goods in a stall at any place” (including taxicabs, beauty salons, and barber shops), and “the production of exercise books and other basic stationery.”

Foreign investors are allowed to create businesses in other sectors, but only if they meet some tough requirements. For example, “a person who is not a citizen may engage in a trading enterprise if that person invests in that enterprise no less than one million United States dollars,” and “employ[s] at least twenty skilled Ghanaians.” The definition of trading “includes the purchasing and selling of imported goods and services” but, in a typically mercantilist fashion, trading for the purpose of exporting Ghanaian goods is not restricted.

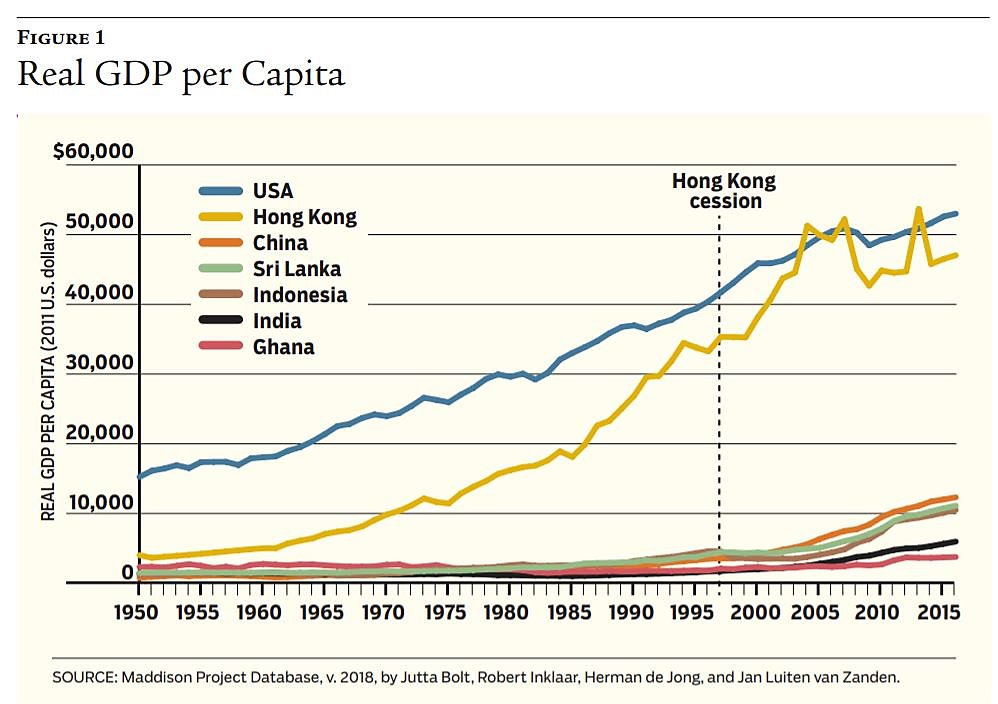

Ghanaians also suffer from tariffs and other trade barriers. The latest Freedom of the World index ranks Ghana 113th out of 162 in freedom to trade internationally. Other developing countries on the list include Indonesia (94th), India (131st), and Sri Lanka (143rd), showing they too are ensnared in protectionist cultures and policies. China ranks 99th; before President Trump launched his trade war, the United States ranked 55th.

Hong Kong and investment / Restricting both foreign investment and imports is not inconsistent. What is inconsistent is what the current U.S. administration does: restrict imports and claim to favor foreign investment. Other things being equal, the two move together because foreign investment is one way in which foreigners spend the dollars (or other foreign currencies) they earn from exports. The fewer imports come into a country, the less foreign investment flows in. If a country restrains imports, it discourages foreign investments, and vice-versa.

Consistent openness to the world is good economic policy. Consider Hong Kong, which has had no tariffs and virtually no non-tariff barriers since World War II. (Hong Kong ranks first in the world on both the general Freedom of the World index and its international trade component.) In 1950, the gross domestic product per capita of this tiny territory with no natural resources was 26% of American GDP per capita. By the time the territory was ceded to the Chinese government in 1997, the ratio had reached 85%. It then eclipsed the United States, before the Great Recession and a subsequent difficult recovery slowed Hong Kong down. Moreover, the future of what has become a world financial center has certainly not been boosted by the tightening grip of the Chinese government.

Figure 1 compares Hong Kong to the countries mentioned above. Hong Kong’s remarkable growth rate surpassed even China’s until the cession of the former to the latter (marked by the vertical bar). Hong Kong’s general free-market environment helped this, but the specific freedom to trade internationally certainly played a major role, as economic theory and most econometric studies suggest. The liberalization of trade in China and some other developing countries explains part of their recent growth.

Escaping the absurd game / For several decades, Western governments and institutions encouraged developing countries to liberalize foreign trade, first with the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and then the 1995 launch of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The resulting growth in international trade finally led to a dramatic reduction in world poverty. But some countries liberalized their trade to a broader extent than others or started liberalization earlier. It is tragic that, within a surprisingly short period of time starting around Donald Trump’s election, the U.S. government stopped supporting trade liberalization.

One reason why liberalization has screeched to a halt is that it was based on a misunderstanding that could justify protectionism as well as free trade: that the benefits of trade come from exports and that imports are the cost to pay for these benefits. Nobel economist Paul Krugman explored this in a 1997 paper, “What Should Trade Negotiators Negotiate About?” (Journal of Economic Literature 35[1]: 113–120). His answer is nothing, because it is in the interest of the vast majority of a country’s residents to not be subject to import restrictions whatever foreign governments do. As the late economist Joan Robinson quipped, protectionist retaliation is as sensible as “dump[ing] rocks into our harbors because other nations have rocky coasts.” Krugman argues that the economist’s case for free trade is essentially a case for unilateral free trade.

So, what can we do in the real world, where everybody seems intent on playing an absurd game where governments declare to each other, “If you hurt your subjects with import restrictions then I will hurt mine too”? What can we do to push the real world toward more rational trade policies?

First, a change of perspective is needed. If trade negotiators and their bosses read Krugman’s article, perhaps they would continue trade negotiations but they would look at them differently. They would stop making “concessions” of the sort, “I agree to stop limiting my citizens’ freedom to import if you do the same for yours.” Instead, they would negotiate with other governments to mutually limit themselves: “Help us limit the capacity of our state to intervene in trade by agreeing to a treaty that will likewise restrain you from intervening.” A free-trade treaty helps states resist the lobbying of their own producers against the common interests of their consumers. As Krugman put it, “The true purpose of international negotiations is arguably not to protect us from unfair foreign competition, but to protect us from ourselves.”

If free trade treaties help do this, they are good. If, on the other hand, they embody the point of view of exporters — for example, by imposing minimum wages on foreign competitors, as the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) would do to Mexico — then they are not good because they fuel the misleading view of free trade as a tool for producers. (See “Is NAFTA 2.0 Better than Nothing?” Winter 2018–2019.)

Second, it is necessary to educate the public and create a constituency that appreciates the benefits of free trade. The message to our fellow citizens should be that whatever other national governments do to restrict the freedom of their citizens, our government should not do the same. Measures of unilateral free trade attenuate the detrimental effects of foreign protectionism. Trump’s trade wars may have aided in this education process by showing consumers that they pay the tariffs that their government nominally imposes on foreign producers.

Some might think this approach is unrealistic. It is certainly politically challenging, but not unwinnable. Hong Kong has shown the way. Another example is the abolition of the corn laws in mid-19th-century Britain after a group of intellectuals and activists taught the common people that domestic tariffs on wheat imports increased the price of their daily bread. With good social, political, and economic institutions, every country could be Hong Kong (hopefully without China).

Developing-world think tanks in the Atlas network are trying to change public opinion in that direction. We have to do the same in America and other developed countries.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.