In recent years, the executives who run the nation’s airports have argued that the country faces a dire need to rebuild its aging and heavily used airports to ensure safe, comfortable, and timely air travel for millions of passengers. The urgent picture they paint is at the heart of an intense lobbying campaign to convince Congress to increase a levy known as the Passenger Facility Charge (PFC), intended to help with airport maintenance. Their plea is finding receptive ears at a time when global competition requires the United States and other nations to maintain and modernize their transportation infrastructure.

But do airports really need this particular funding stream to undertake infrastructure modernization projects? The short answer is no. Airports have mechanisms to self-fund these improvements by raising takeoff and landing fees, as well as further expanding airport concessions. Beyond that, the federal government already provides airports with billions of dollars in infrastructure grants to fund improvement projects. So why have airports so single-mindedly focused on convincing Congress to increase the PFC rather than, say, seeking other revenue streams, including more grant money from the federal government?

A Hidden Tax

The PFC is one of 17 unique taxes levied on airline tickets. Few passengers are aware of what most of these taxes pay for. More often than not, they assume — wrongly — that any increase at the ticket counter represents a fare hike, not a tax hike. This is partly due to the fact that these taxes are tacked on to the airfare in a relatively opaque fashion.

Proposals to raise the PFC have bounced around Congress for the past few years, propelled by a vigorous campaign by the airports and their allies. Proponents of raising the tax note that it has not kept up with inflation. They also say airports need more money in order to serve the steadily increasing volume of travelers each day.

The current tax is capped at $4.50 per “segment” (leg of a trip), with the actual amount set by the individual airports with Federal Aviation Administration approval. The fee is charged at the ticket counter and pocketed by the airport that collects it. Current proposals in Congress would increase the cap to $8.50, though there is talk of an even higher limit.

Not all airports charge the fee, but a lot of them do. Since the inception of the PFC in 1992, 399 airports have been approved to collect the tax, according to the FAA. Today, 362 airports assess the PFC, with 350 of them setting it at the maximum level. Those that do not tax at the cap level are mainly airports classified as providing non-hub primary or non-primary commercial service.

Is a PFC Increase Justified?

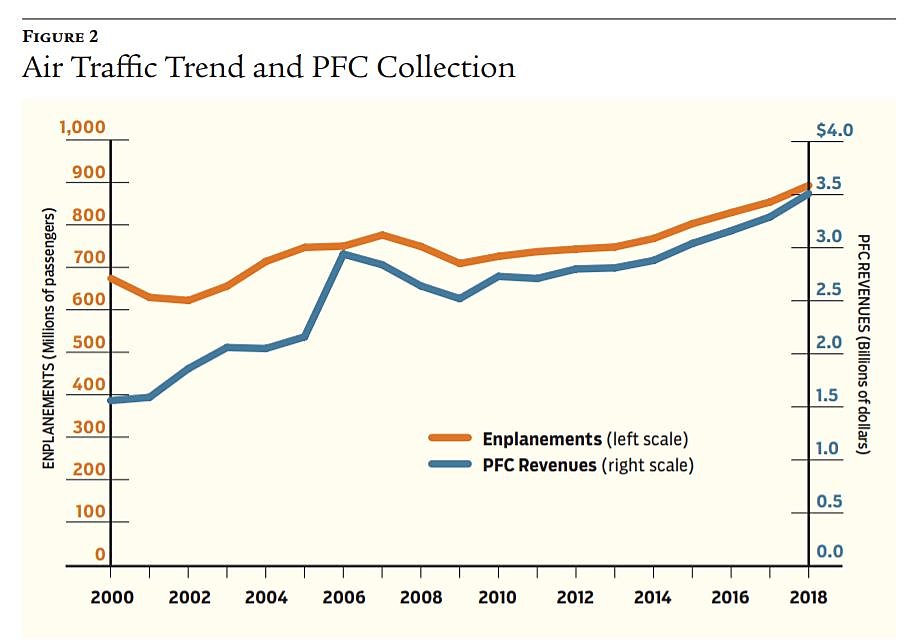

Federal data suggest that PFC revenue has been exceedingly robust, even though the cap hasn’t been adjusted for inflation since 2000. PFC revenue per passenger has increased by 49% since the tax’s inception, a figure well above the rate of inflation over that period, according to an analysis of airport financial statements.

In addition, airports generate a significant amount of revenue in other ways. There is, for instance, the rent that airport restaurants and other retail establishments pay. Airports also receive revenue from the airlines for the takeoff and landing slots they provide. As a result, the airports have plenty of cash on hand to cover costs and pay for investments.

The FAA requires airports to be as self-sustaining as possible and to collect, at a minimum, enough revenue to cover operational expenses. Total revenues, operating and non-operating, for U.S. airports have increased significantly in recent years as airport authorities have (belatedly) taken a page from the innovations of privately-run airports in the rest of the world and offered new shopping and dining experiences to travelers.

Airport revenue increased from $10.75 billion in 2000 to $27.4 billion in 2018. Although operating expenses have also increased, U.S. airports still generated $1.3 billion in operating income in 2018. In addition, they have $16 billion in unrestricted cash and investments on hand that can be used without external restrictions, equivalent to 396 days of liquidity.

Furthermore, most airports have strong credit ratings, allowing them to access capital markets at lower rates. Given the significant funds airports already generate and can access, an increase in the PFC cap rate seems unnecessary.

Alternative Sources for Funding

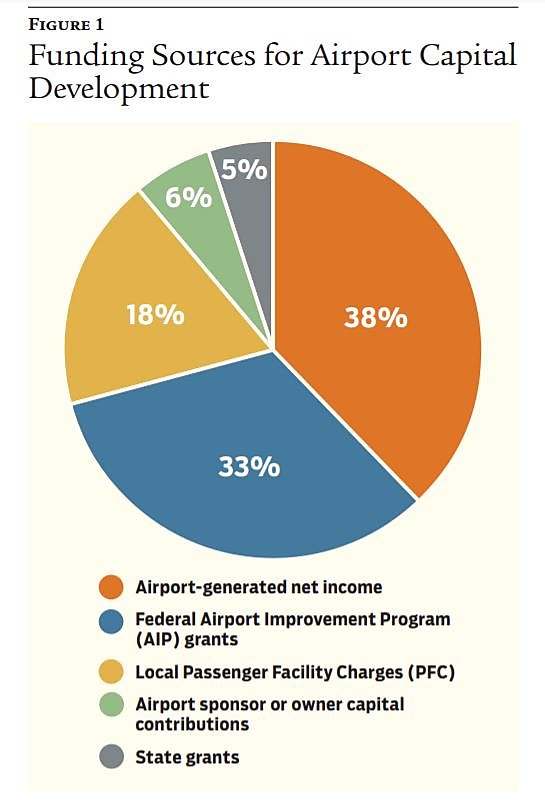

There are five categories in which airports can generate funds for capital improvements. The two largest sources are airport-generated net income and grants from the federal Airport Improvement Program (AIP). Given this funding structure and recent air travel trends, there are ways for airports to generate additional funds without increasing the PFC cap.

As shown in Figure 1, airport-generated net income accounts for 38% of capital development funds from both aeronautical and non-aeronautical income sources. That revenue totaled roughly $10 billion nationally each year from 2009 to 2013. Revenues from landing fees or leases with airlines are considered aeronautical revenues, which have seen a major increase in the past two decades. Revenues from airline landing fees have nearly doubled, while those from landing-related activities (e.g., terminal arrival fees, rents, utilities, federal inspection fees, terminal area apron charges, and the like) have more than doubled. Total aeronautical revenues, nationally, have increased from $5 billion in 2000 to $12.6 billion in 2018.

Non-aeronautical revenues, on the other hand, include earnings from terminal concessions, parking fees, car rental fees, hotels, and other potential revenues from landside operations. This source of revenue has also increased, going from $5 billion in 2000 to $10.6 billion in 2018. These revenue streams will continue to increase in the coming years.

Larger airports also obtain significant revenues from sources like advertising. These airports are more likely to be self-sufficient in funding and cash flow.

Smaller airports have fewer funding sources and often find themselves financially strapped. For these airports, one alternative source is AIP money from the FAA. AIP funding mainly comes from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF), which had a $17 billion cash balance at the end of 2018. In 2016, the AATF had an uncommitted balance of approximately $5.7 billion. This uncommitted balance is expected to grow, reaching approximately $17 billion by the end of 2026. In addition, AIP also received $1 billion in discretionary funding in 2018 and an additional $500 million for airport grants. In 2020, AIP grants will receive another $3.3 billion in funding.

Though abundant, the FAA allocates these funds disproportionately. Large, medium, and small hubs handle 97% of passenger volume, but they receive only 39% of obligated AIP funding. Non-hub primary and non-primary commercial service airports, reliever airports, and general aviation airports receive the rest of the AIP money. Since AIP funding and PFCs are complementary, the FAA should make efforts to reallocate AIP funding more efficiently in the case of insufficient PFC revenues.

Why Do Airports Love the PFC?

The entities that oversee airports, which in the United States are almost always municipalities or other government entities, greatly appreciate the revenue generated via the PFC because it represents a stable source of income. And it comes with virtually no strings attached, unlike other federal funding programs that have strict rules on expenditures. The FAA may specify that these funds be used for projects to “enhance safety, security, or capacity; reduce noise; or increase air carrier competition,” but at the airport level the reality is that these funds are highly fungible.

While the FAA must approve all PFC-funded projects, rejections are rare. As of June 2019, 2,541 applications had been partially or fully approved under the program and only six had been denied. Given the high PFC application approval rate, it is worth asking whether the public is getting the best bang for its infrastructure bucks. Airports arguably possess some of the best infrastructure in the United States and most of the hubs with high traffic volume or a large carrier presence either already have state-of-the-art technology, terminals, and infrastructure, or are in the middle of expensive renovation projects to attain that status.

In the last decade alone, the nation’s 30 largest airports have undertaken over $130 billion in modernization projects. Some have been completed, others are underway, and some have received approval to move forward. For example, New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, Los Angeles International Airport, and Chicago’s O’Hare Airport each have multi-billion-dollar upgrades in progress.

It is not clear how closely the FAA examines the efficacy of projects funded with PFC dollars. Prior to 2002, the FAA did not review PFC audits on a regular basis, and although it now performs such audits annually, the guidelines for them have not been updated since then. The multiple major mergers in the airline industry should alone warrant updates to guidelines and monitoring for PFC collections and allocations.

Dampening Air Travel

Demand for air travel appears to be relatively inelastic. In other words, when the price of air travel increases, the quantity demanded goes down by a smaller percentage than the price increase.

But this is not to suggest that increasing the PFC to $8.50 is “minor,” as the FAA recently claimed in its own review of a possible PFC increase. For a roundtrip ticket with two segments each way, the total PFC charged per person would increase from a maximum of $18 to $34. For a family of four, this fee increase would add as much as $64 to the trip, for a total PFC of $136. Using the average domestic fare of $350 in 2018, such a hike could increase average total airfare by 4.6%, more than double the current inflation rate. Removing the PFC cap altogether, as some in Congress propose to do, would enable airports to raise the tax even higher.

What’s more, behavioral economics suggests that a price increase caused by a tax increase may be treated differently by flyers than an outright fare increase. There is evidence that passengers react more strongly to tax changes than to equivalent price-induced changes. This may seem nonintuitive at first blush — why should a consumer care why a ticket price went up? — but there are several different but complementary explanations for this behavior:

- Tax hikes are not uncommon in the airline industry. For example, the FAA has increased the segment fee several times in the past decade, and the September 11 Security Fee increased in 2014. From the consumer’s standpoint, these tax increases accumulate and become more persistent than price or cost fluctuations.

- Consumers may not always know which taxes are being increased or by how much they are increasing, but they do know they are now paying a higher tax for air travel. Psychological responses such as tax aversion may arise, making passengers respond to tax changes more strongly than to price changes.

Figure 2 plots the total enplanements (domestic and international passengers boarding) and PFC revenues from 2000 to 2018. The number of enplanements relates directly to PFC revenues. According to FAA reports, PFC revenues are expected to be $3.66 billion in 2020. With the steady growth in the number of passengers depicted by the trend line, those revenues should also be steadily increasing.

All that said, a study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office concluded that the proposed increase in the PFC cap would reduce air travel demand and slow or stop passenger growth. It forecast that a 1% increase in the tax-inclusive fare leads to a 0.8% decrease in passenger volume. That means that although increasing the PFC cap would increase PFC revenues, it would also lead to lower passenger volume. That, in turn, would result in lower ad valorem tax revenue, an important source of income for other funds the FAA allocates to airports. It could also negatively affect the rents airport restaurants and shops are willing to pay for space, as well as the fees that air carriers are willing to pay for airport facilities use.

What’s more, the resulting diminution in quantity demanded might lead carriers to stop operating some marginally profitable routes (typically regional routes involving small communities) as well as delay or cancel new or inaugural flights. This would cause airports not to receive the expected additional PFC money and slow the growth of air service.

Conclusion

Although proponents of increasing the PFC cap argue that it needs to keep up with inflation, actual airport revenue per passenger — which includes PFC money and income from concessions — has increased significantly since the charge’s inception. Airports also have strong credit ratings and liquidity, allowing them to access resources at lower rates. And it is worth noting that airport infrastructure seems to be in better shape than the rest of the nation’s infrastructure.

While airports like money from the PFC because it is a stable — and fungible — income source, it is far from the only source for airports, and an increase in the PFC may diminish some of those other revenue streams. With the abundance of cash balance, uncommitted balance, and additional funding approved by Congress, a PFC cap increase appears to be unnecessary.

An increase in the cap would lead to a substantial increase in total airfare. Research suggests it would have a greater effect on demand than a price-equivalent increase. That could slow passenger growth and potentially hinder airline network expansion.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.