Should a business be legally compelled to deal with a patron whose lifestyle it finds objectionable on moral or religious grounds? This is the seminal issue in several lawsuits that have been filed on behalf of gay couples who have been denied goods and services. The business owners claim their refusal of service is protected on First Amendment grounds: they should not be compelled to conduct business with gay couples whose marriage offends the owners’ beliefs as protected by constitutional rights to freedom of religion, speech (expression), and association. The gay couples claim this denial of service is illegal discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation. This standoff will soon go before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Public sentiment varies widely on how these disputes should be resolved. Progressives argue that discrimination is never justified — full stop. Those in the middle of the political spectrum may find it morally objectional for a business to refuse service on the basis of sexual orientation, but may not be comfortable with the business being legally compelled to do so. Libertarians tend to view this issue in terms of restrictions on the use of private property. Specifically, the business owner, rather than the government, should decide with whom he engages commercially because otherwise private property is no longer private. This concern is exacerbated by the progressive mantra, “You didn’t build that,” and what it may portend.

Another problem with these disputes concerns permitting the courts to decide what constitutes a legitimate religious belief. To wit, if the only way a business can justify “discrimination” is to anchor its objections in First Amendment protections, it will naturally be inclined to do just that. In other words, there must be a constitutional protection that is violated if the government compels the business to serve certain customers; the business owner is not free to state that he simply does not want to. Suppose, for example, that a landlord is a member of the Snake-Handlers Sect of Dunceford, MS and objects to renting his apartment to two gay men on grounds that it violates his religious beliefs. The court would then have to weigh in on the legitimacy of those beliefs and whether they should prevail over the right of the two gay men not to be discriminated against on the basis of their sexual orientation.

Did the Founders really intend for the courts to determine what constitutes a legitimate religious belief? In “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments,” James Madison observed:

The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right.

In Federalist 51, Madison was prescient in recognizing that a constant vigil was required to protect against government encroachment:

But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

The thesis of this article is that there are three discrete mechanisms by which behavior can be regulated: legal compulsion, moral suasion, and economic pressure. Legal compulsion is one of the most invasive measures by which government can regulate behavior. Moral suasion can exert some motivating influence, but may be found wanting in terms of overall effectiveness. Economic pressure by way of a discrimination tax may prove increasingly effective in the age of social media given its ability to materially affect the demand for goods and services. A discrimination tax forces the business owner to pay a price for his objectionable conduct, but in most cases this falls short of an outright ban on the conduct in question. In cases where the courts must abridge one party’s rights in order to preserve the rights of another party, economic pressure may be a preferable alternative, although it is not without its drawbacks.

Becker’s Discrimination Tax

Economics Nobel laureate Gary Becker posited that discrimination is unsustainable in a competitive market because businesses that engage in discrimination do not utilize their inputs efficiently (e.g., refusing to hire skilled minorities) and therefore have higher costs than those of non-discriminating rivals. This difference in costs is a de facto tax paid by discriminating businesses that forces them to exit the market and, in so doing, administers the requisite discipline on bad actors. In line with Chicago School doctrine, the market disciplines “bad behavior” and there is little or no need for government intervention. While the discrimination tax may be an elegant theoretical construct, the government has nonetheless seen fit to intervene in these markets with laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, gender, religion, and sexual orientation.

Despite the multitude of cases to come before the Supreme Court that seek to determine whether businesses should be compelled to serve gays even if service would abridge the business owners’ right to freedom of religion or speech, the Court has so far failed to rule definitively on which parties’ rights should prevail. In the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, the court ruled narrowly in favor of bakeshop owner Jack Phillips, finding that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission displayed “a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs motivating his objection.” The high court left undecided whether a business owner’s rights to freedom of religion and speech can justify his refusal to transact business with gays. In similar cases involving Oregon baker Sweet Cakes by Melissa and Washington state florist Arlene’s Flowers and Gifts, the high court remanded the cases back to the state courts for further adjudication. In the Oregon case, the state argued that “baking is conduct, not speech” in contending that “a bakery open to the public has no right to discriminate against customers on the basis of their sexual orientation.” This deferral on the part of the high court is not unusual; it tends to rule on the narrowest of principles, signaling its unwillingness to resort to a legal compulsion remedy in matters as politically charged as these have proven to be.

Juxtaposed against this vacuum of legal remedies is the question of whether some variant of Becker’s discrimination tax may provide a remedy short of legal compulsion. Like virtually every other dimension of modern society, technology has engendered a paradigmatic shift in the marketplace and the discrimination tax is no exception. Technological advance in the form of social media may have transformed Becker’s discrimination tax from an intriguing academic construct into a workable remedy when legal compulsion is deemed too blunt an instrument.

The Discrimination Tax in the Age of Social Media

Businesses face a demand schedule for the goods and services that they sell. This demand schedule exhibits an inverse relationship between the price of the good and the quantity demanded of the good so that higher prices result in the business selling fewer units of output and conversely, ceteris paribus. “Ceteris paribus” figures prominently here because there is a multitude of factors other than price that determine the demand for goods and services (e.g., quality, tastes, income, prices of complements and substitutes, etc.). When one of these other factors changes, there is a shift of the demand schedule, as opposed to a movement along the demand schedule, which is what would occur if there were a change in the price of the good. For example, a business may advertise to positively influence the perceived quality of its services; if this advertising has the desired effect, it shifts the demand schedule outward and the business sells more output at any given price than it did previously.

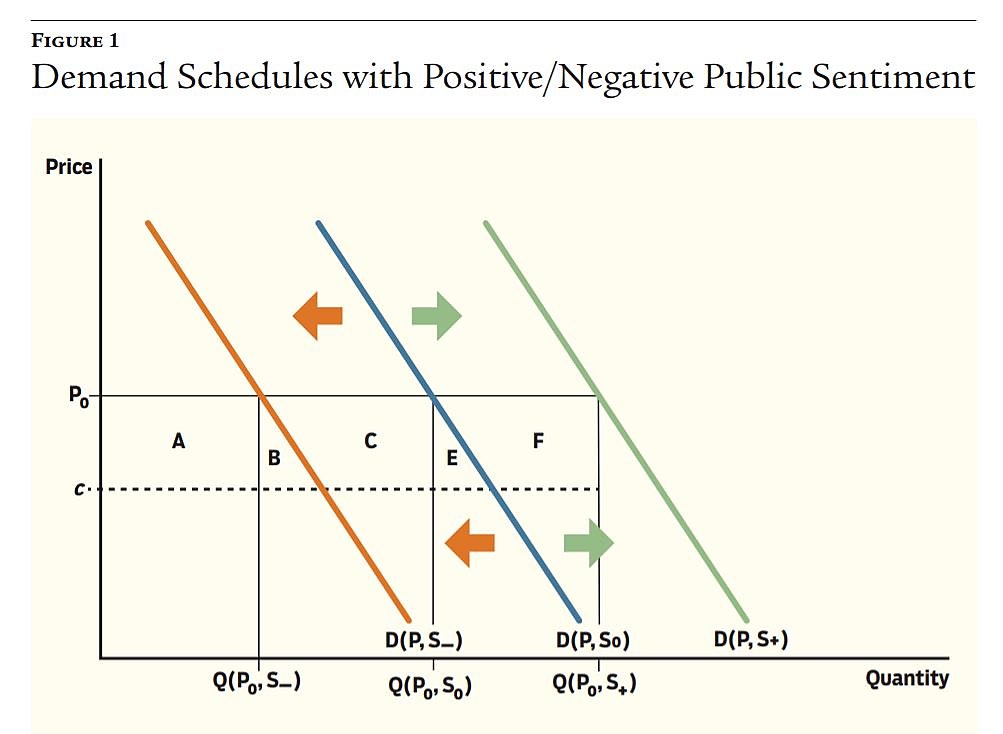

Social media, including Facebook, Instagram, and Yelp, provide another avenue through which businesses can benefit from or be harmed by positive and negative sentiment, respectively. Positive reviews on social media can be expected to shift the demand schedule outward while negative reviews can be expected to shift the demand schedule inward. In the latter case, the business sells less output at any given price than it did prior to receiving the negative reviews. Social media is the modern-day manifestation of picketing and may be used to express negative or positive sentiment with regard to business conduct. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

The initial demand schedule for the business is indicated by the line D(P, S₀), where S₀ represents the baseline level of public sentiment, P₀ is the prevailing market price, and c represents the constant marginal cost. There are no fixed costs. The baseline profits for the business are equal to its revenues minus its costs, or Q(P₀ , S₀) × (P₀ – c), and correspond to the area A + B + C in Figure 1. Suppose the business engages in conduct that elicits negative public sentiment as indicated by the change from S₀ to S−. That would result in an inward shift of the demand schedule from D(P, S₀) to D(P, S−). The new level of profits is equal to Q(P₀ , S−) × (P₀ – c) and is denoted by the area A. As a result of the negative public sentiment, the business suffers a loss in profit of (A + B + C) – A = B + C. This loss in profit represents the discrimination tax. Conversely, if the business generates positive public sentiment, the demand schedule shifts outward from D(P, S₀) to D(P, S+). The resulting gain in profits is given by (A + B + C + E + F) – (A + B + C) = E + F.

This analysis demonstrates the manner in which social media has transformed Becker’s discrimination tax into an instrument that allows public sentiment to collectively weigh in on the conduct of the business in either an approving or disapproving manner with corresponding effects on demand and profits. The discrimination tax does not manifest itself in the form of more costly inputs that render the business no longer competitive, as in Becker’s original formulation, but rather a shift inward of its demand schedule, which in the extreme case may have the same effect.

Social media has given rise to a discrimination tax that affects the demand side vis-à-vis the supply side of the market. The discrimination tax may also turn into a credit if there is net positive public sentiment for the conduct of a business. For example, despite practices that some find objectionable, the weight of the market evidence is that Chick-fil‑A has not been harmed in the court of public opinion by some of its executives’ stated beliefs about gay marriage. This may suggest that the collective public sentiment is neutral to positive.

Costs and Benefits

There are benefits as well as costs associated with using a discrimination tax as a prospective market alternative to the remedy of legal compulsion. On the benefit side, the discrimination tax may be seen as more democratic in that it turns on the collective sentiment of the public rather than nine (unelected) justices in Washington, DC. In addition, this approach allows the courts to defer to public opinion in determining whether the constitutional right of the business owner should prevail over the right of the customer to be protected from discrimination, or vice versa.

The costs are likewise multidimensional. The majority rule is not synonymous with just rule; there is no guarantee that the rights of the individual will be respected. The public sentiment registered over social media may include individuals who are not part of the market and therefore are not “voting with their feet” insofar as patronizing the product. This can create a “mob-like” mentality that permits those without “skin in the game” (including “bots”) to voice approval or disapproval.

In the case of the Oregon bakery, the public outcry on social media, which included threats of violence, was so vehement that the bakery was forced to close its brick-and-mortar business and retreat to an on-line presence. This raises the question of whether the social externalities associated with business conduct are such that they legitimize participation by those who are not market participants per se. It should be noted, however, that there is no assurance that those who physically picket in front of a business — negatively in the form of making it more difficult for would-be buyers to patronize the business, or positively in the form of voicing support for the business — are actual market participants.

Conclusion

A discrimination tax propelled by the intensive use of social media in the modern age may offer a middle ground for adjudicating issues on which the Supreme Court opts not to invoke the remedy of legal compulsion. Moreover, as many of these cases transcend the law and spill over into hyperbolic political discourse, the high court may find that a discrimination tax permits it to side-step issues on which it believes it risks losing public support.

The legal cases in question pit the rights of gays to be protected from discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation against the rights of business owners to exercise freedom of religion, speech, and association. These are zero-sum games in that one of the parties will have its rights abridged. The high court may find that deferring to the court of public opinion by way of the marketplace and a discrimination tax has substantial appeal in that, whatever the outcome, the democratic process has spoken even though certain interest groups will not like what it says.

Readings

- “Are Firms that Discriminate More Likely to Go Out of Business?” by Devin Pager. Sociologic Science 3: 849–859 (2016).

- “The Discrimination Tax,” by Keith Payne. Scientific American, December 10, 2013.

- The Economics of Discrimination, by Gary S. Becker. University of Chicago Press, 1957.

- “The Turnabout on Religious Freedom,” by Martin Swaim. Wall Street Journal, June 21, 2019.

- “Why Employer Discretion May Lead to More Effective Affirmative Action Policies,” by Dennis L. Weisman. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 13(1): 157–162 (Winter 1994).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.