America is losing jobs in the funeral industry. Many are good-paying jobs, albeit morbid ones. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of funeral directors, embalmers, and attendants decreased from 59,217 in 2000 to 50,815 in 2012. That’s a 14.2% drop in just 12 years, despite a rising number of deaths as older baby-boomers reach the end of their lives. One might have thought that funeral industry employment would be rising, not falling.

Why is the number of jobs decreasing? It’s not because the Chinese are taking them or undocumented immigrants are doing them. It’s because of changes in technology and tastes, leading to an increase in the cremation rate. People who choose cremation are less likely to have their loved ones embalmed and to have visitations. As a result, funeral directors are spending less time in embalming preparation rooms and parlors. They are also spending less time in conference rooms because it takes less time to help customers pick out urns than caskets and to arrange memorial services than funerals.

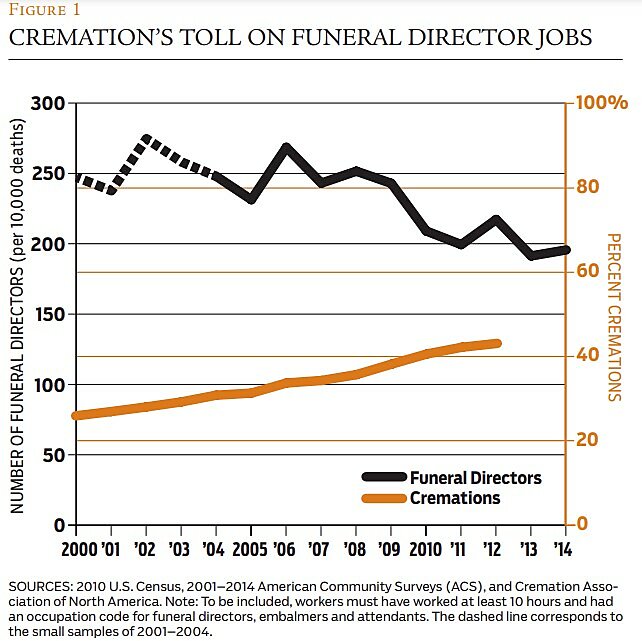

Figure 1 illustrates the toll that the increasing popularity of cremation is taking on funeral directors’ jobs. As the cremation rate increased from 25.9% in 2000 to 43.1% in 2012, the number of funeral directors decreased from 247 per 10,000 deaths to 217, and then fell further to 196 in 2014.

The story I’m telling is one of changing demand. Of course, it is also possible that fewer people are willing to enter the profession of caring for dead bodies over time, causing a decrease in the supply of funeral directors. If so, we would expect wages to have increased in order to coax more people into caring for dead bodies. That’s not what’s happening. The wages of salaried, full-time funeral directors decreased from $28.22 per hour in 2000 to $22.33 per hour in 2012, measured in 2016 dollars. They also worked fewer hours per week over that time—the average number of hours worked decreased by four hours per week among those who worked at least 10 hours per week.

Is government doing anything to save these jobs? Yes, state governments are. In the next part of this article, I describe two examples of how states have recently changed their laws to protect funeral directors from decreases in demand caused by the growing popularity of cremation. Of course, this was not the story proponents pitched to lawmakers in order to get the changes they desired; instead, they argued that the changes would protect consumers against poor-quality cremations. In the second part of this article, I investigate whether state “ready-to-embalm” laws protect funeral directors against the rising tide of cremations by privileging traditional funerals over low-cost cremations.

CLOSING A LOOPHOLE IN GEORGIA

On an atypically warm day in February 2002, a woman walking her dog in northwest Georgia stumbled upon a human skull. Her discovery was the first of 339 bodies that investigators would find on the grounds of the Tri-State Crematory. The bodies were littered in the woods, abandoned in sheds, stuffed into vaults, dumped into ponds, and discarded in rusting hearses. A few still had toe tags. Some were recognizable. Most were difficult to identify. Urns that the crematory had given to funeral homes, which were then passed on to the families of the deceased, contained powdered cement mixed with burnt wood chips and potting soil. Some bodies were never found.

The families had not dealt directly with the crematory because it sold its services only to funeral homes. The crematory charged $200 to $250 per cremation, which included picking up the body and delivering the “ashes” to the funeral home. One funeral director characterized the amount Tri-State charged as a “rock-bottom” rate. Another said he had not visited the crematory since the 1980s. Neighbors couldn’t remember when they last saw smoke from the crematory, or smelled its faint but distinctive odor.

The Tri-State Crematory scandal was big news in 2002, especially in Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee, where funeral directors had contracted with Tri-State for cremation services. More than two-thirds of the 387 newspaper articles on Lexis/Nexis that mentioned the scandal in 2002 appeared in those states’ newspapers. After the story broke, consumers must have wondered whether they could trust crematories to handle their loved ones responsibly. The growth of cremations in the three-state area slowed noticeably after the scandal, before bouncing back in 2004.

Three days into the scandal, journalists began asking why government regulators had not caught such egregious behavior. Georgia’s governor, Roy Barnes, pledged to seek new regulations to prevent similar scandals in the future. Others began talking about closing a loophole in the state’s funeral laws.

To understand that loophole, we need to return to 1992 when Georgia had last changed its laws concerning crematories. Legislators had pretty much ignored crematories up to that point because there were so few of them. But their numbers were growing, especially around Atlanta, as consumers increasingly chose cremation. In 1992, Georgia enacted a law requiring crematories open to the public to be licensed, submit to inspections, and employ full-time licensed funeral directors, who in Georgia must also be embalmers. Tri-State Crematory had to do none of those things because it was a wholesaler, not a retailer of cremations.

The loophole was closed in 2002 with the deletion of the words “which is open to the public.” Hence, Georgia now requires crematories that are independent of funeral homes to hire specialists in embalming, a skill that is useless for independent crematories and those specializing in low-cost cremations. But Georgia did much more than just close the loophole. It slammed the door shut on independent crematories by requiring them to have many of the facilities required of funeral homes, including chapels with seats for at least 30 mourners. The only important exception is that they don’t have to have embalming preparation rooms.

Talk about raising rivals’ costs! It’s like requiring bus companies to hire airline pilots and build runways next to their terminals.

Requiring crematories to hire licensed funeral directors is an unusual licensing requirement. Scanning state statutes, I could find only two other states with this requirement: Idaho and Oklahoma. No other state requires crematories to have chapels. Not surprisingly, Georgia has very few independent crematories, ones that are operated outside of funeral homes. An industry directory—nicknamed the Yellow Book by industry professionals—currently lists 97 crematories in Georgia. Only two are independent of funeral homes: one is located in a cemetery and the other in an industrial park.

Impeding the entry of independent crematories increases costs for two reasons. First, crematories operated by funeral homes are less likely to exploit economies of scale. For example, 13.3% of the 165 crematories in Florida in 2012 were operated independently of funeral homes, based on data from Funeral Industry Consultants. Independent crematories in Florida performed, on average, 976 cremations in 2012, compared to 591 by those operated by funeral homes. Using cremation retorts—the furnaces used for cremation—more intensively drives down average costs since modern cremation retorts are capable of completing cremations in 60 to 90 minutes.

Second, funeral homes without crematories spend more time traveling to cremation services providers because they prefer not to have cremations done by local rivals in the funeral industry. Economist Lori Parcel estimates that the extra travel costs raise the price of cremations by 4% in markets without independent crematories. The price of cremations is also likely to be higher in markets without independent crematories because independent crematories tend to offer lower wholesale prices.

What is the cost to consumers of saving funeral directors’ jobs via Georgia’s slamming the door on independent crematories? Here’s a rough calculation:

Suppose the percentage of independent crematories in Georgia would have been the same as in Florida without Georgia’s law and that Georgia’s independent crematories would not have willingly hired embalmers. Assuming no change in the total number of crematories, Georgia’s law would have saved 11 jobs.

Suppose the law caused the retail price of cremations to rise by 4%. It’s easy to quibble over using Parcel’s figure to estimate the cost of saving jobs. I like it for two reasons. First, it’s produced by a rigorous study that establishes that the absence of independent crematories increases the retail price of cremations via the increased travel costs of funeral directors. Second, I think it’s an underestimate because it doesn’t incorporate the effects of lost economies of scale and greater market power created by the law.

Given that there were 24,735 cremations in Georgia in 2012 and that the average retail price for cremation nationally is roughly $3,200, Georgia consumers are spending nearly $300,000 for each funeral director’s job preserved by the law. The average earnings of salaried funeral directors in Georgia are $49,354, according to the most recent five-year sample of the American Community Survey. Hence, consumers are spending nearly $300,000 annually for each $50,000 job that they’re saving via the protectionist Georgia law.

RETAKING CHARGE OF CREMATIONS IN FLORIDA

In 1978, the Federal Trade Commission wrapped up a 10-year investigation of the funeral industry with a blistering report that accused funeral directors of exploiting vulnerable consumers. The FTC lawyers presented a mountain of testimony about how funeral directors strong-armed consumers into purchasing excessively expensive funerals. Above all else, the lawyers argued, funeral directors aimed to “discourage[e] the use of alternative forms of disposition, notably direct cremation and other low cost services.”

State legislators in Florida must have heard about the FTC’s investigation. Shortly after the release of the final report, they created a new type of occupational license for people specializing in selling cremations that include neither a viewing nor memorial service—a package of services called a “direct cremation” within the industry. The legislators called the new occupation, a bit disparagingly, “direct disposers” and imposed much less extensive requirements on them than funeral directors. The legislators also created a separate license for direct cremation establishments, which could be operated out of the operator’s home or the backroom of a funeral home.

Prior to 1979 only licensed funeral directors were legally permitted to sell cremations in Florida. They weren’t happy about their new competitors but confidently predicted that direct cremation would never account for more than 1% of the state’s cremations. They were wrong. By 1999, direct cremation firms were handling 20% of the state’s cremations.

The Florida Funeral Directors Association (FFDA) lobbied Florida legislators to rein in direct cremation but didn’t have much luck until 2004 when they convinced legislators to bar operators from operating out of their homes or the backrooms of funeral homes. Six years later, in 2010, the FFDA convinced legislators and the governor to require direct cremation firms to employ a full-time licensed funeral director to supervise their operations. Sound familiar? It’s a lot like Georgia’s law. As of 2010, funeral directors were once again in charge of cremations in the state of Florida.

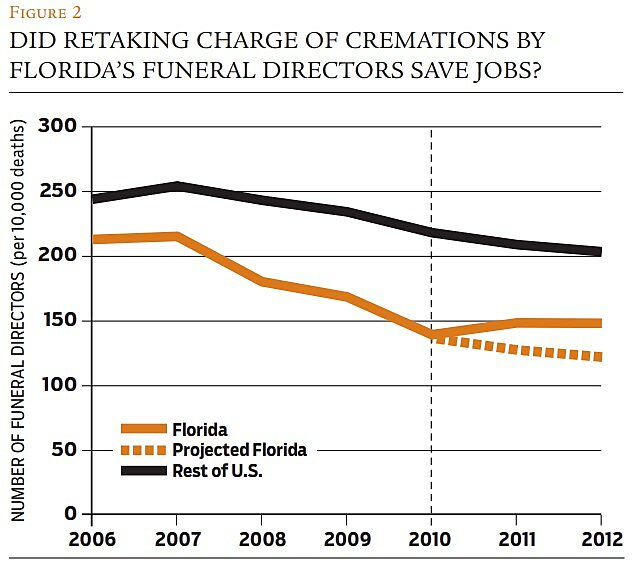

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of the change in Florida’s law. The change appears to have stopped the decrease in the number of licensed funeral directors, saving 254 funeral directors’ jobs if the trend would have been the same as elsewhere had the law not been changed. That’s a 6% increase over 2010. I think it’s plausible given the importance of direct cremation firms and the extent to which they have been throttled by the changes in the law.

COUNTERING CREMATION WITH READY-TO-EMBALM LAWS?

Back in 1910, funeral directors gathering at their national convention in Detroit had one thought on their minds: how to reduce the number of funeral directors and undertakers so as to make the occupation more prosperous. The National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA) initially conspired with casket manufacturers, but that scheme was shot down by the courts. It had more luck with state legislators and governors, convincing them to enact licensing laws that imposed training requirements on funeral directors. It was so successful that the NFDA “largely wrote the modern statutory law of the dead,” according to a 2013 article by Wake Forest law professor Tanya Marsh.

Much of the law focuses on the qualifications to be an embalmer, which is a skill that funeral directors believe places them in the same league as surgeons. Just as surgeons need operating rooms, embalmers need embalming preparation rooms. At the beginning of the 20th century, the NFDA lobbied state legislatures to require all funeral homes to have embalming preparation rooms and all funeral directors be trained to use them. These “ready-to-embalm” laws have been defended on the grounds that funeral homes should always be prepared to touch up bodies in a timely fashion even if they had been embalmed elsewhere.

The NFDA used the licensing of funeral directors to reduce the overcrowding problem and improve the prosperity of funeral directors. The rising popularity of cremation resurrects the overcrowding problem because it erodes the prevalence of embalming and, as a result, is a threat to the prosperity of funeral directors. The stringent licensing of funeral directors based on ready-to-embalm laws has become more important to the NFDA even as it has become more archaic. I expect that the NFDA will use the licensing laws that it largely wrote to mitigate the threat of cremation to the prosperity of its members, perhaps by slowing its growth or by dampening its effects on funeral expenditures.

Putting the brakes on cremation? / States with ready-to-embalm laws have more funeral directors and lower cremation rates than the states without these laws. But the trends are remarkably similar to states without such laws, mirroring what is presented in Figure 1. Cremation rates are rising and the number of funeral directors are falling everywhere. Between 2000 and 2012, the cremation rate increased by 18.1 percentage points in ready-to-embalm states and 14.4 percentage points in states without these laws. Hence, ready-to-embalm laws are not powerful enough to put the brakes on the growth in the popularity of cremation, but may temper the decrease in the number of funeral directors.

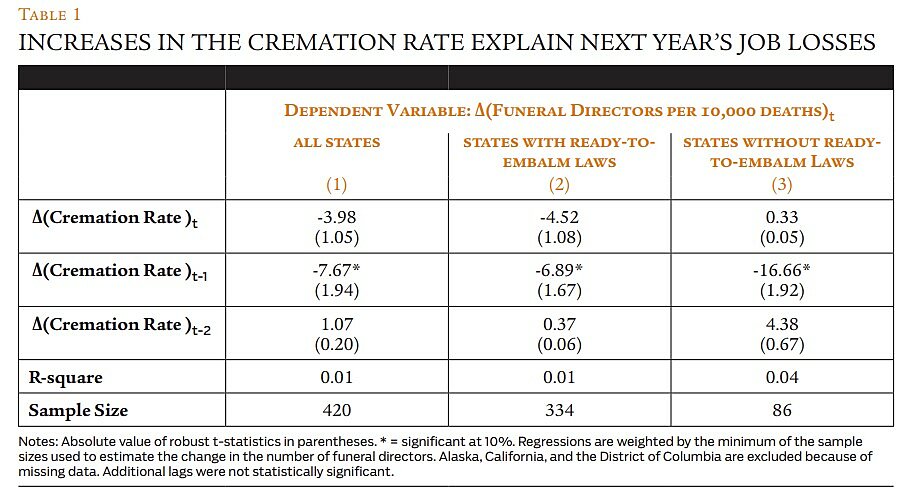

Table 1 presents the results of regressing yearly changes in the number of funeral directors on contemporaneous and lagged changes of the cremation rate using data on 48 states over 12 years. Both of the one-year lags of the cremation rate are statistically significant. What this means is that states experiencing larger increases in the number of people choosing cremation have fewer funeral directors, but not immediately. It takes a year to see the effects of an increase in the cremation rate on the employment of funeral directors. That earlier changes in cremation rates help explain later job losses increases my confidence that the estimates are causal because it implies that contemporaneous omitted variables are not generating the results.

Consider the case of Minnesota, where according to the Twin Cities Pioneer Press, “Cremation rates [have] steadily crept up a percentage point or two each year so that by 2011 [cremation was more popular than burial].” The largest “creep” was 3 percentage points between 2005 and 2006. Since Minnesota is a ready-to-embalm state, the regression results presented in column (2) can be used to predict the effect of this one-year creep on the number of funeral director jobs. Using the coefficient on the lagged cremation rate, we predict that this number would have fallen by 21 per 10,000 deaths one year later, i.e., between 2006 and 2007. Using all three coefficients, the number of funeral directors would have fallen by 33 per 10,000 deaths over three years. Given that the annual number of deaths at the time was 37,500, we predict that Minnesota lost 124 morbid jobs—funeral directors, embalmers, and attendants—because of that single creep.

It could have been worse for Minnesota’s funeral directors. They could have lived in nearby Missouri, which is not a ready-to-embalm state. Using the regression results from column (3), we predict that Minnesota would have lost an additional 11 jobs from that single creep had it not had its ready-to-embalm laws.

Over the years 2000–2012, the cremation rate in ready-to-embalm states increased by 18.1 percentage points. Using the same basic approach as with the Minnesota creep, I estimate that the ready-to-embalm laws saved 16.6 morbid jobs per 10,000 deaths in states with these laws. Given that the average annual number of deaths in ready-to-embalm states was 1,726,238, I estimate that ready-to-embalm laws saved 2,965 morbid jobs between 2000 and 2012.

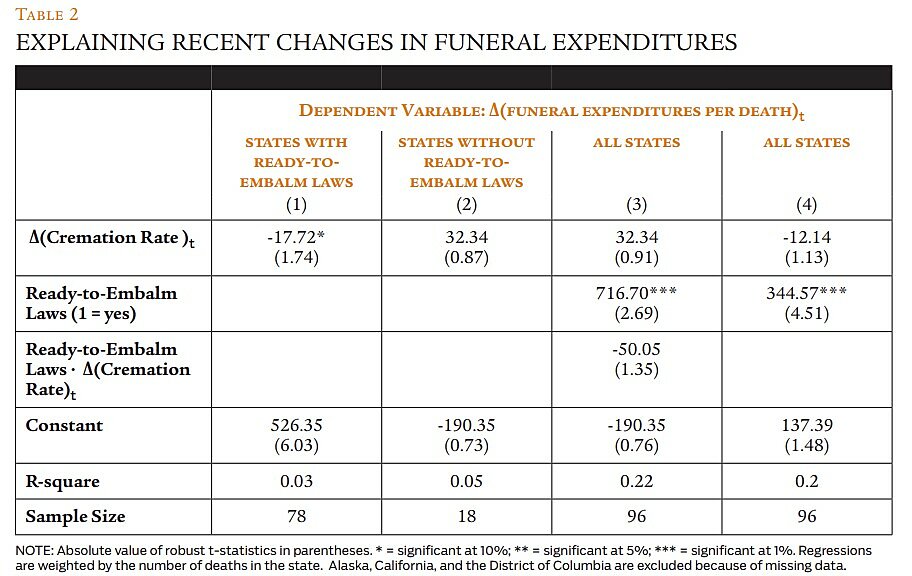

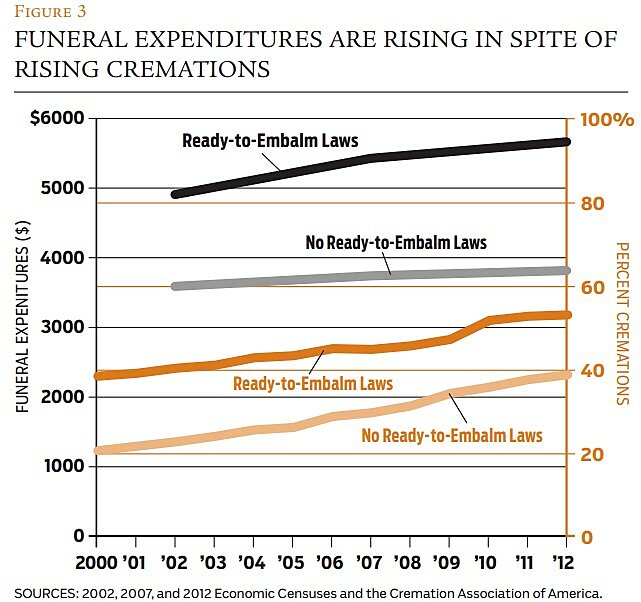

Expenditures keep rising? / Figure 3 illustrates the trends in funeral expenditures (per death) over time in states with and without ready-to-embalm laws. The data on funeral expenditures are only available every five years from the Economic Census while the cremation data are available annually. The amount people spent at funeral homes barely changed in states without ready-to-embalm laws but continued to rise in states with the laws.

The first two columns of Table 2 present regressions that explain changes in funeral expenditures using only changes in the cremation rate between the years of the three most recent Economic Censuses. The change in the cremation rate is statistically significant only for the sample of states with ready-to-embalm laws, suggesting that consumers in those states can reduce their funeral expenditures by choosing cremation. Given that the cremation rate increased by 16.0 percentage points between 2002 and 2012 in states with ready-to-embalm laws, the coefficient implies that consumers saved, on average, $284 per death because of the rising cremation rate. If the savings only accrued to the third of consumers who chose cremation, then they would have saved $852 per death. Surprisingly, the change in the cremation rate does not explain changes in funeral expenditures in states without ready-to-embalm laws.

The third regression tells us that the difference in the coefficients on the change in the cremation rate in the first two regressions is not statistically significant, which is not surprising given how imprecisely these coefficients are measured, especially in the small sample of states without ready-to-embalm laws. The last regression drops the interaction term, principally to make it easier to interpret the effect of ready-to-embalm laws on the change in funeral expenditures. It tells us that funeral expenditures have been rising faster in states with ready-to-embalm laws than those without them. Consumers could mitigate the increase by opting for cremation, but the net effect was still positive even when I added an interaction term to the specification.

Ready-to-embalm laws saved approximately 2,965 jobs over the 13 years from 2000 to 2012 at the cost of higher expenditures on caring for the dead. A job that would have been lost in the first year saves 13 years of employment; a job that would have been lost in the last year saves only one. Spreading the jobs saved linearly over those years implies that 19,273 years of employment were saved by ready-to-embalm laws. Spreading the more rapid rate of funeral expenditures linearly over those years implies that typical consumers in ready-to-embalm states had their funeral expenditures rise by $382 more than elsewhere. Multiplying by 22.4 million deaths in ready-to-embalm states and dividing 19,273 years of employment implies that consumers in ready-to-embalm states are paying an extra $443,979 per year of employment saved. In contrast, the average earnings of salaried funeral directors in ready-to-embalm states are $46,255, according to the most recent five-year sample of the American Community Survey.

Conclusion

Over the last half century, American funeral directors have experienced a decrease in the demand for their services as consumers have increasingly chosen cremation over burial. No longer is nearly every body embalmed, nor does nearly every funeral involve a visitation at the funeral home. With each funeral director having less to do, the country needs fewer of them than it once did.

The National Funeral Directors Association has attempted to protect its members by lobbying for new state laws that would create supervisory positions for licensed funeral directors at firms that specialize in cremations and by defending ready-to-embalm laws that raise the barriers against the entry of new funeral directors. Requiring firms that do not offer embalming services to hire trained embalmers raises their cost and is a form of featherbedding. These protectionist policies save jobs, but at a high cost. My back-of-the-envelope estimate is that consumers are being forced to spend an extra $300,000 to $450,000 annually for each job saved.

Shocks routinely hit labor markets, leading to losses of jobs in some industries and gains in others as well as losses in some countries and gains in others. Some labor markets have been hit by a combination of shocks—technological, immigration, and trade shocks—making it difficult to isolate what factor is responsible for the changes we see. Most of the proponents of populist policies aimed at protecting American jobs emphasize the role of immigration and trade, downplaying the importance of technological shocks.

The market for funeral directors has been hit with a shock closely akin to a technology shock and is largely unaffected by immigration and trade. This makes it a clean example of the potential cost of saving jobs being lost to changes in technology and tastes. It is tempting to save jobs that would be lost with protectionist policies such as those used to save funeral directors’ jobs. But it is often costly and ultimately futile when the shocks are as powerful as the rising popularity of cremation on the funeral industry.

Readings

- “Markets: Preserving Funeral Markets with Ready-to-Embalm Laws,” by David E. Harrington. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 21, No. 4 (2007).

- “Rethinking the Law of the Dead,” by Tanya D. Marsh. Wake Forest Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 5 (2013).

- “State Funeral Regulations: Inside the Black Box,” by Jerry Ellig. Journal of Regulatory Economics, Vol. 48, No. 1 (2015).

- “Stiff Competition: Vertical Relationships in Cremation Services,” by Lori Parcel. Discussion Paper 07–041, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, 2008.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.