Late last October, European leaders accepted the inevitable and the Greek government defaulted on its public debt. Officially, the country and its lenders agreed to a modification in the terms of Greek bonds, but it’s difficult to construe the large “haircut” imposed on the lenders as anything but a default.

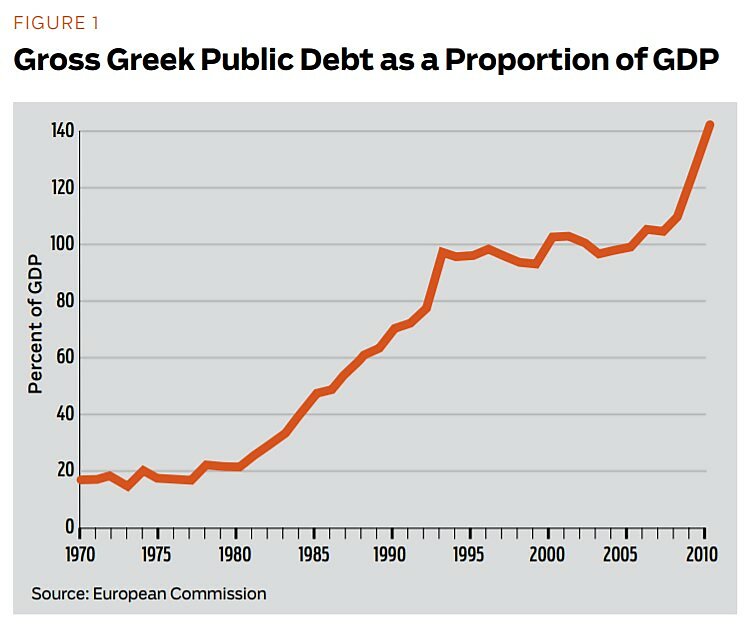

The reason for the default is simple: over the past decades, the Greek state had built up an unsustainable public debt that other European taxpayers did not want to shoulder. The crucial fact is that the Greek debt problem is essentially structural and not a consequence of the recent recession, which merely precipitated the catastrophe. Data from the European Commission show that the ratio of Greek public debt to gross domestic product, which reached 143 percent in 2010, was already 105 percent in 2007. In the 1970s, the ratio was around 20 percent of GDP but, from 1980 to 1994, it exploded to 96 percent (see Figure 1). Most of the damage was done long before the Great Recession struck.

Part of Greece’s problem is the stagnation of tax revenues. In 1995 (the first year that Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development data are available), government expenditures stood at 46 percent of Greek GDP, 7 points below the euro-area figure of 53 percent. However, government revenues in Greece were 37 percent of GDP, whereas the euro area’s was 46 percent—a gap of 9 points. Greek taxpayers did not want to pay for high government expenditures and the state was not able, or not willing, to enforce higher taxes.

Beyond Greece | The already wide discrepancy between expenditures and revenues in the euro area (7.5 percent in 1995) points out that something has long been rotten in Europe at large. There too, the taxpayers were not paying for all the goodies they received from the state. In other words, Greece is not alone in having a structural deficit and public debt problem. With few exceptions (Ireland, Spain, and the Northern countries), European countries were, before the Great Recession, riding a trend of high public deficit and indebtedness that had started in the 1970s.

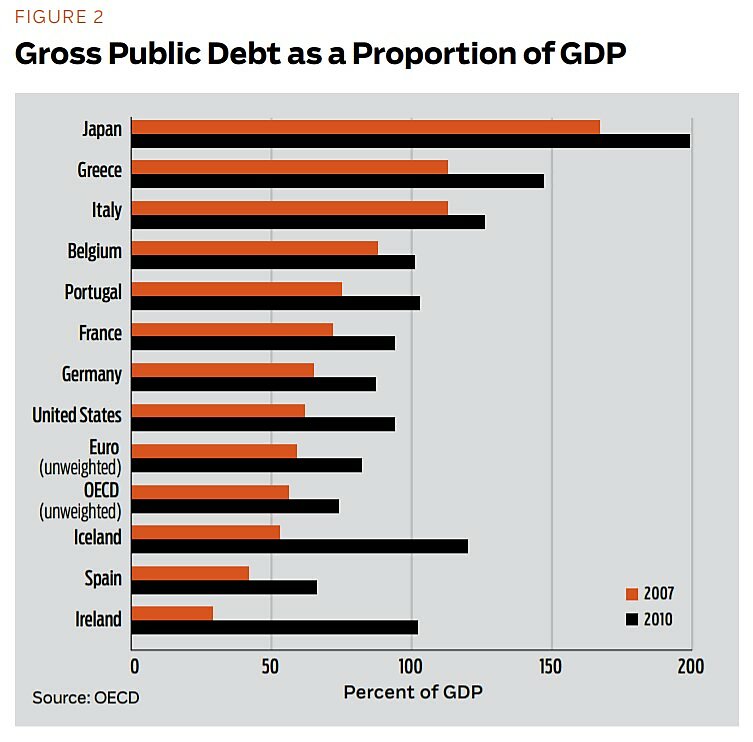

Consider Figure 2, which compares gross public debt as a proportion of GDP in selected countries before and after the Great Recession. In 2007, the gross public debt in the typical euro-area country was 59 percent (unweighted average) of GDP, which amounts to nearly three-fourths of the level of 82 percent reached in 2010. In other words, nearly three-fourths of euro-area public debt was accumulated before the Great Recession and, in fact, before the mid-1990s.

With gross public debt at 113 percent of GDP in 2007 (OECD statistics differ slightly from the EU’s), Greece and Italy came second and third in public indebtedness only to Japan (a special outlier). Note how Belgium (88 percent), Portugal (75 percent), France (72 percent), and even Germany (65 percent) were also pulling up the euro-area average. In all these countries, the level of public debt was already, in 2007, 73 percent or more of what it would reach after the Great Recession. A similar situation obtained in the whole OECD: by 2007, the typical member state had accumulated 75 percent of its 2010 debt.

In the United States, the ratio of gross public debt to GDP in 2007 was 66 percent of what it reached in 2010. Only the usual strength of the American economy prevents investors from being nervous about U.S. government securities—for now.

Note that these ratios of public debt to GDP underestimate the weight of pre-recession debt, as the reduced GDP boosts the post-recession ratio.

Two factors propelled this high level of public indebtedness. The first factor is the growth of government expenditures, especially the growth of the welfare state. Even in the United States, which has been spared the worst excesses, total government expenditures increased from about 8 percent of GDP before World War I to 37 percent in 2007 (and 42.5 percent in 2010). The second, related factor lies in the endemic deficits that have developed since the mid-1970s, and which Public Choice theorists James Buchanan and Richard Wagner had diagnosed in their prescient 1977 book, Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes.

Excluding record tax evasion and cooked statistics in Greece, the same structural factors that brought the Greek state to default are at work in other European countries and the United States. The aging of the population will only make matters worse.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.