The authors thank Colleen Chien, Dennis Crouch and Michael Risch for comments. They also express their appreciation to Tim Layton for research assistance, the patent information firm PatentFreedom for data, and the Coalition for Patent Fairness and the Kauffman Foundation for support.

In 2010, firms operating in the United States found themselves in lawsuits initiated by nonpracticing entities (NPEs) more than 2,600 times. That is a five-fold increase over 2004. Is this trend worrisome?

NPEs are firms that do not produce goods. Rather, they acquire patents in order to license them to others. In principle, NPEs can perform the socially valuable function of facilitating markets for technology. Some inventors lack the resources and expertise needed to successfully license their technologies or, if necessary, enforce their patents. NPEs provide a way for these inventors to earn rents that they might not realize otherwise, thus providing them with greater incentives to innovate. For example, economic historians find evidence of a robust market for technology during the 19th century that allowed individual inventors to earn returns on their inventions in the era before the rise of the large research and development laboratories. Optimists argue that the current crop of NPEs perform a similar function and should not be discouraged.

Critics, including many technology firms, compare these NPEs to the mythical trolls who hide under bridges built by other people, unexpectedly popping up to demand payment of tolls. The critics call NPEs "patent trolls," claiming that they buy up vaguely worded patents that can be construed to cover established technologies and use them opportunistically to extract licensing fees from the real innovators. Indeed, there has been a general and dramatic rise in patent litigation that some analysts attribute to rapid growth in the number of patents with unclear or unpredictable boundaries.

To the extent that the recent NPEs opportunistically assert "fuzzy patents" against real technology firms, they can decrease the incentives for these firms to innovate. Innovators deciding to invest in new technology have to consider the risk of inadvertent infringement as a cost of doing business. This risk reduces the rents they can expect to earn on their investment and hence decreases their willingness to invest.

This article makes several findings about this litigation. First, by observing what happens to a defendant's stock price around the filing of a patent lawsuit, we are able to assess the effect of the lawsuit on the firm's wealth, after taking into account general market trends and random factors affecting the individual stock. We find that NPE lawsuits are associated with half a trillion dollars of lost wealth to defendants from 1990 through 2010. During the last four years, the lost wealth has averaged over $80 billion per year. These defendants are mostly technology companies that invest heavily in R&D. To the extent that this litigation represents an unavoidable business cost to technology developers, it reduces the profits that these firms make on their technology investments. That is, these lawsuits substantially reduce their incentives to innovate.

Second, by exploring publicly listed NPEs, we find that very little of this loss of wealth represents a transfer to inventors. This suggests that the loss of incentives to the defendant firms is not matched by an increase in incentives to other inventors.

Third, the characteristics of this litigation are distinctive: it is focused on software and related technologies, it targets firms that have already developed technology, and most of these lawsuits involve multiple large companies as defendants. These characteristics suggest that this litigation exploits weaknesses in the patent system. In the 2008 book Patent Failure, two of us (Bessen and Meurer) argue that patents on software and business methods are litigated much more frequently because they have "fuzzy boundaries." The scope of these patents is not clear, they are often written in vague language, and technology companies cannot easily find them and understand what they claim. It appears that much of the NPE litigation takes advantages of these weaknesses.

While the lawsuits increase incentives to acquire vague, overreaching patents, they decrease incentives for real innovation.

We conclude that the loss of billions of dollars of wealth associated with these lawsuits harms society. While the lawsuits increase incentives to acquire vague, overreaching patents, they decrease incentives for real innovation overall.

Data and Methods

The data for this research come from two primary sources. The first source is an extensive database of NPE lawsuits generously provided by PatentFreedom, an organization devoted to researching and providing information on NPE behavior and activities. PatentFreedom defines nonpracticing entities as companies that "do not practice their inventions in products or service, or otherwise derive a substantial portion of their revenues from the sale of products and services in the marketplace. Instead, NPEs seek to derive the majority of their income from the enforcement of patent rights." Since we study litigation, we only focus on those NPEs that file lawsuits ("patent assertion entities").

The second data source is the Center for Research in Security Prices' (CRSP) U.S. Stock Database, a comprehensive collection of security information. Using these sources, a sample comprised of all instances in which a known NPE sued a publicly traded firm between 1990 and October 2010 was constructed. This was done by first matching defendant names with a previously constructed list of public domestic firms and subsidiaries using a software program, and then manually reviewing the resulting list and updating matches that had been either missed or incorrectly assigned by the software. To assess the validity and coverage of the matches, a random sample of 100 parties was manually checked using corporate websites and CRSP's Company Code Lookup tool. For this sample, while 11 percent of parties that were either public companies or their subsidiaries were left unmatched, there were no false positives.

This process yielded a sample of 1,630 lawsuits filed by an NPE against one or more publicly listed defendants. Because many of these lawsuits were filed against multiple defendants, the total number of events in the sample was substantially higher than the number of suits, at 4,114 (for the sample using a five-day window to measure the returns).

Finally, we linked the data in our sample to Compustat and to data from Derwent LitAlert, a source of data about patent and trademark litigation, to obtain information on firm characteristics and patents involved in the lawsuits. We also used financial information on publicly listed NPEs from Compustat.

Estimating cumulative abnormal returns | To estimate the impact of a lawsuit filing on the value of a firm, we use event study methodology. In particular, we use the dummy variable method. This assumes that stock returns follow a market model,

(1) rt = α + β rtm + ɛt

where rt is the return on a particular stock at time t, rtm is the compounded return on a market portfolio, and ɛt is a stochastic error.

If an event such as a lawsuit filing occurs on day T, then there may be an "abnormal return" to the particular stock on that day. This can be captured using a dummy variable,

(2) rt= α + β rtm + δIt+ɛt

where It equals 1 if t = T and 0 otherwise.

Equation (2) can be estimated using OLS for a single event. In practice, this equation is estimated over the event period and also over a sufficiently long pre-event window. In this paper we use a 200 trading-day pre-event window. The coefficient estimate of δ obtained by this procedure is then an estimate of the abnormal return on this particular stock. For different stocks, the precision of the estimates of δ will vary depending on how well equation (2) fits the data. The estimated coefficient variance from the regression provides a measure of the precision of the estimate of the abnormal return.

We want to obtain a representative estimate of the abnormal returns from lawsuit filings for multiple stocks under the assumption that these represent independent events and that they share the same underlying "true" mean. Previous papers estimating abnormal returns from patent lawsuits have simply reported unweighted means for the group of firms. Although the unweighted mean is an unbiased estimator, it is not efficient. Since we are concerned with obtaining the best estimate to use in policy calculations (and not just testing the sign of the mean), we use a weighted mean to estimate the "average abnormal return," where the weight for each observation is proportional to the inverse of the variance of the estimate of δ for that firm.

When we test our means against the null hypothesis that the true mean is zero, we report both the significance of t-tests using the weighted mean and also the significance of the Z statistic, a widely used parametric test of significance that incorporates the variation in precision across events. In any case, the significance test results are closely similar, as are those of some nonparametric tests.

Finally, (2) describes the abnormal return for a single day. It is straightforward to design dummy variables to estimate a "cumulative abnormal return" (CAR) over an event window consisting of multiple consecutive days. In the following, for instance, if the suit is filed on date t = T, then we may use a window from day T – 1 to T + 4.

Empirical Findings

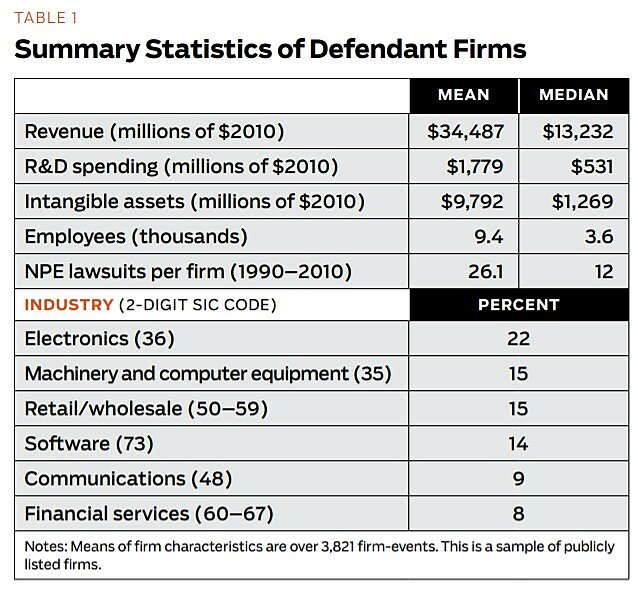

Some characteristics of defendant firms in our sample are reported in Table 1. These are, on average, large firms. Almost two-thirds of the firms are technology companies, including software and communications companies, and these firms, on average, spend a lot on R&D and have very substantial intangible assets. A significant number of financial, retail, and wholesale firms are also represented. These firms are typically subject to multiple NPE lawsuits.

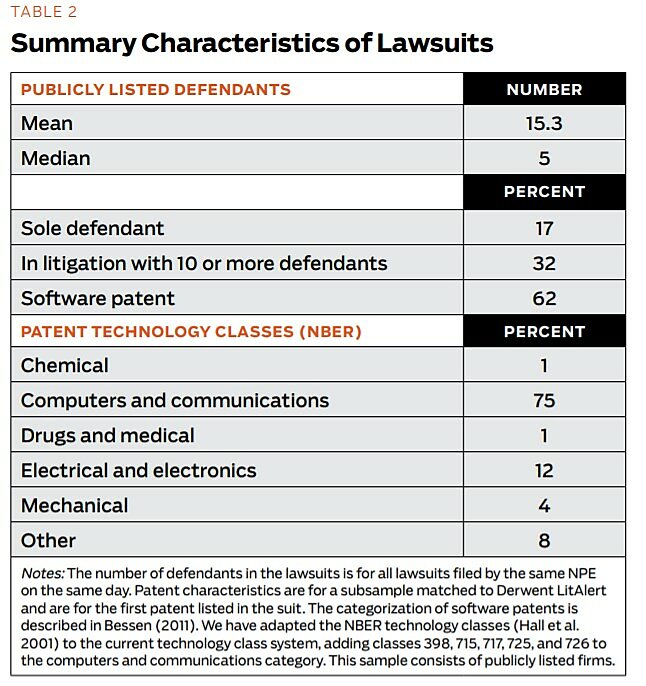

Table 2 shows that most of the NPE disputes involve multiple defendants, either in the same suit or from multiple suits filed by the NPE on the same day. (See also Chien 2009.) The number of publicly listed defendants mostly ranges between two and nine defendants (median of five). Only 17 percent of the defendants were the sole defendant listed. This contrasts sharply with other patent litigation where 85 percent of defendants are solo.

Another difference is the distribution of these patents across technology classes. Looking at the main patent listed in Derwent, about 62 percent of the patents are software patents, using the technology class categorization used in Bessen (2011). Using the National Bureau for Economic Research categorization of firms, 75 percent of the patents are in computer and communications technology. Thus, this sample shows the same concentration of NPE litigation in software and related technologies as in earlier studies. Both this technological concentration and the prevalence of multiple defendants are important for interpreting the nature of the current crop of NPEs.

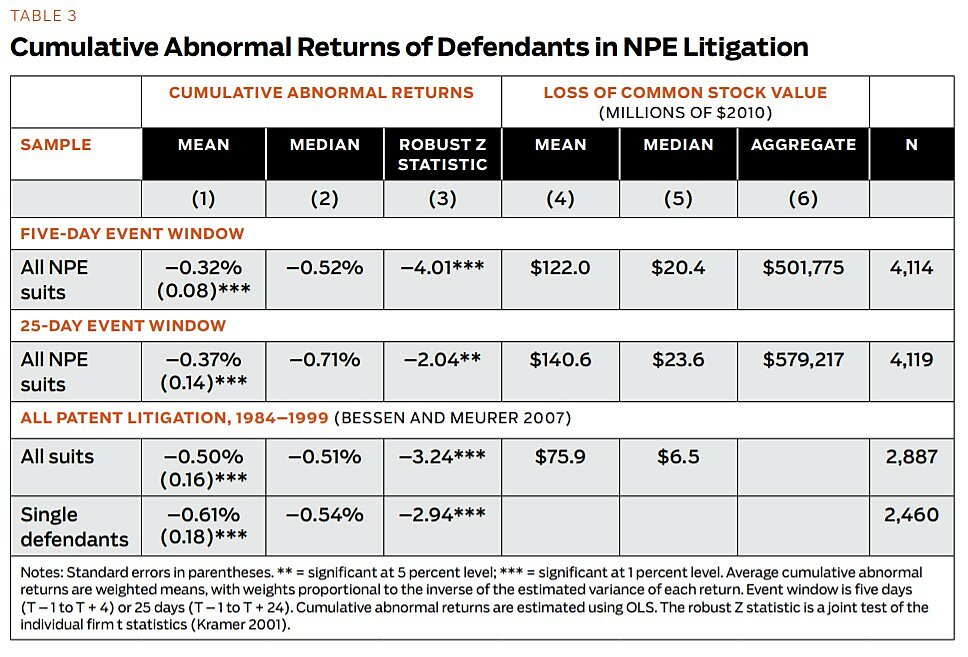

Estimates of cumulative abnormal returns | Table 3 reports basic estimates of CARs for the sample of NPE defendants. Columns 1 and 2 report the weighted mean (with standard error) and median values. The first row shows the results using a five-day event window that starts one day before the lawsuit filing and continues through the fourth day after. The mean loss is 0.32 percent and the median loss is 0.52 percent.

One concern is that this estimate of lost value might reflect a temporary overreaction on the part of investors. Given that there are now hundreds of these troll lawsuits every year, it is hard to understand why investors would consistently overreact and never learn from their mistakes. Nevertheless, a persistent overreaction would be noticed by arbitrageurs who would then come in, buy the artificially low stock, and thus drive the price up to a more accurate level. If it took some time for arbitrageurs to enter, the price we observe during the five-day event window might be artificially low, making our estimate of losses too high.

One way to check this is to look at a longer event window to see if the stock showed evidence of recovery over the subsequent month or so. The second row reports results for a comparable analysis using a 25-day window. If it took some time before wiser investors arbitraged the stock, then we should see some evidence of a price correction within this longer window. Instead, the CARs in this row are slightly larger (more negative) than those in the five-day window. This suggests that the initial loss of wealth was not an overreaction by investors that was subsequently corrected, at least not within 25 days. Because the longer window has larger standard errors as a result of the measurement technique, we use the sample with the five-day event window for most of the remaining analysis.

Perhaps, instead, the stock price stays artificially low until the lawsuit is resolved. This might be the case if investors react to the uncertainty of the lawsuit, demanding a higher return on investment until the uncertainty is resolved. If this were the case, then we should see an increase in the stock price at the announcement that the suit was settled. However, two event studies of lawsuit settlements—Haslem (2005) and Bhagat et al. (1998)—find no such positive correction on average. This suggests that investors overall appear to anticipate settlement correctly, pricing it into the share value. Thus this theory, too, seems difficult to reconcile with the evidence. While we accept the idea that investors do not always act rationally, we have found no explanation consistent with the evidence for why investors should persistently overreact to lawsuit filings.

The estimated CARs are substantially smaller than those found in the study of all patent lawsuits involving publicly listed firms from 1984 to 1999 by Bessen and Meurer (2007). The third row shows the CARs for defendant firms from that study and the fourth row shows the CARs from solo defendant firms in that study. We parse out the results in the fourth row to provide the most relevant comparison to the NPE lawsuits in this study. Most NPE lawsuits in our current study have multiple defendants (83 percent). Most of the lawsuits in our earlier studies involved a single defendant (85 percent); we suspect that almost all of those lawsuits do not involve an NPE plaintiff. The mean CAR for all single-defendant lawsuits is nearly twice as large as the mean CAR reported for the five-day window in the NPE sample. This difference is also statistically significant.

The NPE CARs are also much smaller than those reported in the previous literature on patent litigation event studies. For example, Bhagat et al. (1998) study 33 defendants of patent lawsuits announced in the Wall Street Journal. They find a mean CAR of –1.50 percent, nearly five times larger than the estimate here. Studying 26 biotech firms, Lerner (1995) found a 2.0 percent reduction in the wealth of the defendants and plaintiffs combined.

Why smaller percentage losses? | One clear reason that the NPE lawsuits have lower CARs than in previous studies is that the sample of defendants in the NPE lawsuits is very different from the samples in the earlier studies. Some of those studies found much larger losses but used highly select small samples of lawsuits that had been announced in the Wall Street Journal or Dow Jones News Service. Bessen and Meurer (2007) show that patent lawsuits announced in the Wall Street Journal tended to involve companies with greater capital per employee and higher stock market betas. These factors might be directly related to larger percentage losses on the announcement of a lawsuit.

The lawsuits involving publicly listed firms in Bessen and Meurer (2007) were not necessarily announced, but these, too, show larger percentage losses than in the current sample of NPE lawsuits, although not so much larger. The NPE sample of public firms differs from that sample in two important ways: NPE lawsuits tend to involve larger defendants and multiple defendants.

Although larger defendants tend to have smaller CARs (Bessen and Meurer 2007), size-related differences cannot directly explain much of the difference in the CARs between the samples. The difference in the CARs between small and large firms is simply not large enough to account for the difference in the NPE sample and these small firms only make up 14 percent of the NPE sample in any case.

Nevertheless, the large size of the defendants in the NPE lawsuits and the fact that so many of these lawsuits involve multiple defendants changes the economics of litigation in an important way: in these circumstances, litigation might still be credible for plaintiffs who have a low probability of winning. A lawsuit only poses a credible threat if the plaintiff's expected gains from winning exceed the costs from litigating. The expected gains are the ex ante probability of winning multiplied by the conditional benefits of winning. Normally, a lawsuit with a low probability of winning does not pose a credible threat. However, when a patent has a chance of being interpreted broadly so that it reads on the business of multiple large companies, the payoff from winning might be so large that the threat of a lawsuit is credible even if the probability of winning is low.

This provides another possible explanation for lower-percentage losses found in NPE lawsuits: the plaintiffs in a substantial portion of NPE lawsuits might have low probabilities of winning at court, hence these lawsuits will cause smaller losses to defendants, all else equal. Because many of these suits might involve aggressive interpretations of patent scope, allowing the claims to read on many defendants, they might have lower probabilities of winning, but still provide credible threats because of the multiple defendants. This explanation is supported by Allison et al. (2011) who find that NPE suits with multiple defendants are more likely to settle and, when they do go to trial, the plaintiffs are much more likely to lose (but see Shrestha 2010). This explanation is thus plausible; however, our evidence for it is not conclusive.

Loss of wealth | Nevertheless, just because the percentage loss of defendant firms is smaller in NPE lawsuits, this does not imply that the loss of wealth is small. Using the CAR estimates, we can calculate the loss of wealth that occurs upon a lawsuit filing. Columns 4 and 5 of Table 3 show the mean and median loss of wealth calculated by multiplying the mean CAR by each firm's capitalization. The mean wealth lost per lawsuit is $122 million in 2010 dollars and the median loss is $20.4 million. These figures are substantially higher than the previous estimates for patent lawsuits of all types found by Bessen and Meurer (2007), shown in row 3. These estimates are, of course, much larger than the direct costs of legal fees. They also include the costs of lost business, management distraction and diversion of productive resources that might result from the lawsuit, possible payments needed to settle the suit, and the reduction in expectations of profits from future opportunities that are forestalled or foreclosed because of the suit.

Investors' expectations of future profits are notoriously volatile. To the extent that one might want to gauge the effect of the lawsuits on current profits while excluding expectations about future profits, it is possible to make some crude adjustments to the above figures. One method is to divide the estimated loss of wealth by the ratio of the market capitalization of the firm's common stock divided by the value of the firm's capital assets. This reduces the mean wealth lost to $112 million in 2010 dollars. Alternatively, the loss can be divided by the ratio of the total market value of the firm to the value of the firm's capital assets, reducing the mean loss to $64 million in 2010 dollars. These figures are also quite substantial and, although investors' expectations of future profits might occasionally be "exuberant," our basic estimate nevertheless captures the actual loss of wealth related to the lawsuit.

Thus, although the NPE CARs are lower than the CARs for other lawsuits, the mean loss per lawsuit is larger because the market capitalization of the NPE defendants is that much larger. This, combined with the tendency of NPE lawsuits to involve multiple defendants, means that these suits have an outsized impact on firm wealth. Aggregating over the sample (column 6) shows that NPE lawsuits from 1990 through October 2010 are responsible for over half a trillion dollars in lost wealth (in 2010 dollars). From 2007 through October 2010, the losses average over $83 billion per year in 2010 dollars, which equals over a quarter of U.S. industrial R&D spending per annum. Moreover, because this total is only for publicly listed firms, it likely understates the true loss of wealth resulting from NPE lawsuits.

Private Losses and Social Losses

Whatever the theoretical and historical roles NPEs might have played in facilitating markets for technology, it is clear that the current crop of NPE litigation is responsible for an unprecedented loss of wealth. Is this private loss of wealth to the defendants also a loss to society?

Transfers | These private losses might or might not correspond to social losses. Litigation incurs static social losses when it involves socially wasteful activity. Aside from direct legal fees, litigation often involves a diversion of management resources away from productive activity. It may also involve a loss of consumer welfare. For example, preliminary injunctions can shut down production and sales while the litigation pends. Even without a preliminary injunction, customers may stop buying a product. And the threat of final injunction might require the defendant to rework its product drastically or even abandon it. Frequently, products require customers to make complementary investments; they may not be willing to make these investments if a lawsuit poses some risk that the product will be withdrawn from the market. Furthermore, patent owners can threaten customers and suppliers with patent lawsuits because patent infringement extends to every party who makes, uses, or sells a patented technology without permission, and sometimes to those who participate indirectly in the infringement.

A detailed study of the economic effects of one NPE litigation found that the affected business divisions of the defendant firms experienced revenue declines of about one-third (Tucker 2011). Moreover, the defendant firms avoided releasing any new products in the technology field for two years while the lawsuits proceeded. The litigation not only delayed consumer surplus, but also delayed the development of new technology.

These social losses might be offset if NPE litigation acts like an investment in a reputation for toughness that deters future piracy. We doubt this is the case. There is simply no evidence that a significant number of defendants in NPE suits are pirates; later we discuss evidence showing that they are mostly inadvertent infringers. Furthermore, NPE litigation is rising over time, not declining as it should if the reputational story were true.

A more important consideration is the extent to which private losses arise from transfers of wealth to other parties that do not incur a static loss of social welfare. When defendants make payments to NPEs to settle lawsuits or subsequent to legal judgments, the private loss to the defendant is not socially wasteful. To what extent do the half-trillion dollars in private losses correspond to such expected transfers?

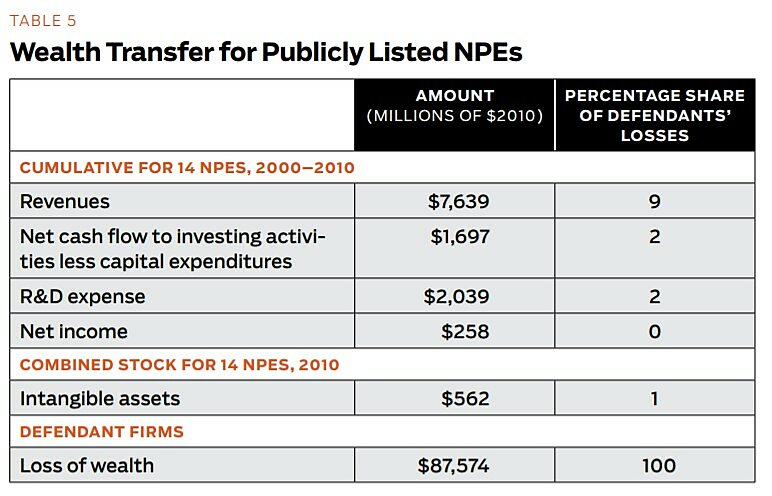

To explore transfers to NPEs and, in turn, transfers from NPEs to independent inventors, we assembled a list of NPE firms in our database that are publicly listed. We identified 14 firms, listed in Table 4. These firms account for 574 litigation events in our data, about 14 percent of the total. The aggregate losses to the defendants in those lawsuits from 2000 through October 2010 total $87.6 billion in 2010 dollars, about 17 percent of the total in our database.

How much of this loss represents a transfer to the NPEs? Table 5 shows the cumulative flow of several financial variables over this same time period. Total revenues over these years come to $7.6 billion, about 9 percent of the total loss to defendants. Revenues necessarily overstate any transfers from the defendants to the NPEs because they also include revenues from firms that are not involved in litigation and from private firms. Nevertheless, it is quite clear that most of the defendants' private loss is not a transfer to NPEs.

Another possible transfer occurs to the defendant's competitors. To the extent that patent litigation causes customers to select a rival product or service, some of the lost business captured in the above calculations represents a transfer to rival firms. Of course, because the NPEs sue multiple parties, it happens frequently that a firm and its rivals are sued at the same time, so that no such transfer would occur. This provides us a simple test of the magnitude of potential transfers to rivals: if such transfers are substantial, we should see smaller CARs when a firm and its rival are sued than in cases where rivals are not sued. We identified 1,914 events (47 percent of the events) where a firm was sued along with another firm in the same Standard Industrial Classification 3-digit industry. However, the CARs for these events were slightly higher than in those cases where a rival firm was not also sued. Thus this test is inconsistent with substantial transfers to rivals.

Another transfer occurs to the lawyers, expert witnesses, etc., involved in the lawsuits. Estimates of legal costs from Bessen and Meurer (2007) suggest these transfers cannot be more than a few percent of the loss.

We also conducted event studies of the NPE stocks around the lawsuit filings. The NPE stocks also lost wealth in that time. Although other factors might cause a drop in the plaintiffs' market capitalizations (Bessen and Meurer 2007), this evidence is not consistent with large transfers of wealth to the NPEs.

In summary, while there are some limited transfers to NPEs and to rivals and lawyers, most of the private losses incurred by defendants in NPE litigation do not appear to be transfers to other parties. Presumably, most of the losses correspond to static losses of social welfare.

Encouraging innovation | Of course, NPE litigation might also produce dynamic gains in social welfare if transfers to independent inventors increase innovation incentives. How much of the transfer to NPEs is subsequently transferred to inventors outside of the NPEs? The investment that NPEs make in acquiring patents is included in the accounting category “net cash flow to investing activities.” This figure less capital expenditures is shown in Table 5. Although this figure includes other investments in addition to payments to outside inventors, it is small compared to the defendants’ losses: $1.7 billion, or about 2 percent of the defendants’ losses. The investments made in patents are also included in the NPE’s intangible assets, although these quantities are amortized.

Table 5 also reports intangible assets for fiscal 2010. It is less than $600 million, about 1 percent of the defendants' losses. Note again that both the intangible assets and the net cash flow to investing activities generate revenues from sources other than our defendants, so these figures might overstate transfers to independent inventors. In any case, we can state that less than 2 percent of the defendants' losses could represent a transfer to independent inventors and quite possibly the true figure is much smaller than 2 percent.

Some of the NPEs also conduct their own R&D. Indeed, capitalized R&D investments are included in the intangible assets of the firm. The R&D expense flows are also not large, around 2 percent of the loss.

It is likely that the R&D investments and acquisitions from outside inventors will yield value to the NPE firms beyond 2010. To the extent that this is true, all of these figures overstate the extent to which these investments are tied to the defendant losses occurring through 2010. That is, some portion of these investments is related to defendant losses that will be incurred after 2010, so only a portion of the investment can be attributed to a transfer of wealth from the pre-2011 defendants.

Although the transfer to inventors is small, it is still positive. Does this mean that NPE litigation nevertheless increases innovation incentives? There are three reasons to conclude that it does not. First and foremost, the losses to technology firms who are defendants in this litigation are two orders of magnitude larger. These losses imply a very large disincentive to innovation for these firms—firms that spend heavily on R&D. Studies show that the more a firm spends on R&D, the more likely it is to be sued for patent infringement (Bessen and Meurer 2005). Moreover, very rarely are the defendants in these lawsuits found to have actually copied the patented technology (Bessen and Meurer 2008, p. 126; Cotropia and Lemley 2009). Instead, they are inadvertent infringers, if infringers at all. This means that they have to anticipate the risk of future lawsuit-related losses as part of their cost of developing new technology and products. This risk is a disincentive to invest in innovation, and our results find that it is a very large disincentive, much larger than any possible incentives provided by transfers to independent inventors via NPEs. Even if incentives to small inventors were much more fertile than incentives provided to large technology firms—producing two, three, or even 10 times as many innovations—the incentives flowing to small inventors would not offset the very much larger disincentives imposed on the technology firms.

Second, to the extent that independent inventors benefit by licensing or selling their inventions to large firms, this risk of inadvertent infringement reduces their innovation incentives as well. Because their prospective licensees have to anticipate the risk of an NPE lawsuit, this risk decreases the amount licensees are willing to pay. Thus the very large losses incurred by defendants tend to reduce the market for technology for independent inventors.

Finally, the incentives provided to patent holders by the current crop of NPEs may be the wrong kind of incentives. NPE activity may skew the research agenda of small firms away from disruptive technologies and toward mainstream technology and associated patents that can be asserted against big incumbents. Even worse, small firms are encouraged to divert investment from genuine invention toward simply obtaining broad and vague patents that might one day lead to a credible, if weak, lawsuit.

To summarize, there are a lot of big losers from NPE litigation, while hardly anyone benefits much. The defendant firms and their customers lose, while patent holders gain very little by comparison. Even the investors in NPE firms have gained little—these firms barely break even based on their cumulative net income in Table 5. Apparently, the only real beneficiaries are the lawyers and perhaps the principals of the NPE firms.

The New Business Model

These findings should be interpreted cautiously. While there are large losses from NPE litigation, not all NPEs today are opportunistic litigators. Nor does this imply that NPEs have not played a more positive role in the past. It is important to understand what is uniquely different about the NPEs that are behind today's litigation surge.

There are a lot of big losers from NPE litigation, while hardly anyone benefits much. The defendant firms and their customers lose, while patent holders gain very little by comparison.

Indeed, today's NPEs tell us they are different. Proponents tell us they are a new breed of company—a new business model—that is misunderstood (McDonough 2006, Myhrvold 2010). They tell us that NPEs are, in fact, good for society because they are creating "a capital market for invention" by buying patents and selling licenses. This helps "turbocharge technological progress" "by realigning market participant incentives, making patents more liquid, and clearing the patent market."

What, exactly, is new about this business model and what does it mean for innovation? Markets for technology have been around at least since the 19th century and studies have documented some of the benefits of those markets (for example, Arora et al. 2004): they give inventors a way of getting money for their inventions, thus providing them with stronger incentives to invent; and they help spread new technologies to the companies that can commercialize them the best. But most of this literature concerns markets for technology, not markets for patents. There is no evidence the transactions occurring around NPE litigation involve the transfer of technology—news reports and judicial opinions indicate the defendants are already using the technology. Instead, these transactions typically occur long after the patents were issued (Allison et al. 2009, Love 2010, Risch 2012) and involve just the transfer of patent rights (and money).

Even so, some advocates hold that NPEs are socially beneficial because they reduce the costs of patent transactions (McDonough 2006). To the extent that NPEs facilitate the clearance of patent rights before firms invest in technology, this is a clear benefit. The patent brokers and auctions facilitate transactions, but that is not obviously true for those NPEs that are primarily involved in asserting and litigating patents. Moreover, to the extent that these NPE transactions occur only after firms invest in technology, any savings in transaction costs has to be offset by the associated dispute costs. We have shown that the litigation losses amount to over half a trillion dollars, so these dispute costs are substantial. No reasonable estimate of the transaction costs of licensing these patents could approach the magnitude of these litigation losses.

There is no evidence that transactions occurring around NPE litigation involve transfers of technology. Instead, these transactions typically occur long after the patents were issued.

The pattern of NPE patent litigation casts further doubt on the view that NPE patent enforcement has any connection to technology transfer. Is it possible that large numbers of innovative firms, in case after case, are pirating the technology disclosed in NPE patents? Why are the numbers so large? Perhaps the firms have colluded to jointly pirate the technology, or perhaps all of these firms have independently decided to pirate the same technology. Not likely. We think the plausible explanation is that the many firms who end up as defendants in these cases have independently created the invention or derived the claimed technology from some source other than the NPE patent.

Multiple inadvertent infringements are especially likely for a general-purpose technology like software. As noted above, NPE lawsuits are concentrated in one technology area: software and software-related patents, including business methods. Consequently, this litigation has a disproportionately large effect on firms working with these technologies. A thumbnail calculation suggests that NPEs account for about 41 percent of patent litigation involving software patents. So NPE litigation is quite significant for this technology.

Thus the new business model for NPEs is not about licensing patents in general; it is mainly about licensing software patents, including patents on business and financial processes (Chien 2009). This is significant because we have argued elsewhere that software patent litigation has risen dramatically because of eroding patent notice and that software patents have been an important contributor to this trend (Bessen and Meurer 2008). That is, software patents have "fuzzy boundaries": they have unpredictable claim interpretation and unclear scope; lax enablement and obviousness standards make the validity of many of these patents questionable; and the huge number of software patents granted makes thorough search to clear rights infeasible, especially when the patent applicants hide claims for many years by filing continuations. This gives rise to many situations in which technology firms inadvertently infringe. And this means that there is a business opportunity based on acquiring patents that can be read to cover existing technologies and asserting those patents, litigating if necessary in order to obtain a licensing agreement. Models by Reitzig et al. (2007) and Turner (2011) show that the patent troll business model only makes economic sense when there is such inadvertent infringement. And the rise in NPE litigation has closely mirrored the rise in software patent litigation (Bessen 2011). Moreover, fuzzy boundaries can explain why so many NPE lawsuits have multiple defendants: many firms may have reasonably concluded that they did not infringe, or the patents were invalid, or they may have been unable to find these patents while conducting a clearance search. Later, they encounter an NPE that sues over an aggressively broad interpretation of the patent's scope and validity.

Thus, "fuzzy boundaries" for software and business method patents enable the rise of this new business model. Large numbers of hidden patents or patents with unpredictable boundaries provide an opportunity to extract rents from technology firms. Further, because NPEs have no operating business, technology firms cannot retaliate with countersuits. Combine this with capital markets to fund the acquisition of patents and to conduct litigation and you get a viable business model. But this is a very different business from the business pursued by those patent brokers, consultants, and auctioneers who facilitate markets for technology.

Conclusion

Firms that buy and license technologies can improve the market for technology and thus improve the innovation incentives for independent inventors. Patent agents and markets for technology have been an important part of the U.S. innovation system since the 19th century.

But the role of the current NPEs who assert and litigate patents is something altogether different. It is focused on software and related technologies, it targets firms that have already developed technology, and it is very much about litigation, especially litigation in the special circumstances where multiple large parties can be sued at the same time. Whatever the general benefits of technology markets, this does not obscure the fact that this particular manifestation involves large amounts of costly litigation. It is hard to believe that markets can be somehow improved by having thousands of lawsuits that incur hundreds of billions of dollars in losses.

We have shown that defendants have lost over half a trillion dollars in wealth—over $83 billion per year during recent years—and this has not improved incentives to innovate. While the lawsuits might increase incentives to acquire vague, overreaching patents, they do not increase incentives for real innovation. The defendants in these lawsuits are firms that already invest a lot in innovation. Their losses make it more expensive for them to continue to do so and it also makes them less willing to license new technologies from small inventors. Meanwhile, independent inventors benefit very little from what the large companies lose.

Readings

- "A Generation of Software Patents," by James Bessen. Boston University School of Law Working Paper No. 11-31, 2011.

- "Alternative Methods for Robust Analysis in Event Study Applications," by Lisa A. Kramer. In Advances in Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, Vol. 8, edited by C. F. Lee. Elsevier, 2001.

- "An Empirical Study of Patent Litigation Timing: Could a Patent Term Reduction Decimate Trolls Without Harming Innovators?" by Brian J. Love. Working paper, 2010.

- "Blackberries and Barnyards: Patent Trolls and the Perils of Innovation," by Gerard N. Magliocca. Notre Dame Law Review, Vol. 82, No. 5 (2007).

- "Copying in Patent Law," by Christopher Anthony Cotropia and Mark A. Lemley. North Carolina Law Review, Vol. 87 (2009)

- "Estimates of Patent Rents from Firm Market Value," by James Bessen. Research Policy, Vol. 38 (2009).

- "Event Studies and the Law: Part I: Technique and Corporate Litigation," by Sanjai Bhagat and Roberta Romano. American Law and Economics Review, Vol. 4 (2002).

- "Event Studies in Economics and Finance," by A. Craig Mackinlay. Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 35, No. 1 (1997).

- "Extreme Value or Trolls on Top? Evidence from the Most-Litigated Patents," by John R. Allison, Mark A. Lemley, and Joshua Walker. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 158 (2009).

- "How Are Patent Cases Resolved? An Empirical Examination of the Adjudication and Settlement of Patent Disputes," by Jay P. Kesan and Gwendolyn G. Ball. University of Illinois Law and Economics Research Paper No. LE05-027, 2005.

- "Inventors, Firms, and the Market for Technology in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries," by Naomi R. Lamoreaux and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. In Learning by Doing in Markets, Firms, and Countries, edited by Naomi R. Lamoreaux, Daniel M. G. Raff, and Peter Temin. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- "Managerial Opportunism during Corporate Litigation," by Bruce Haslem. Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 4 (2005).

- Markets for Technology: The Economics of Innovation and Corporate Strategy, by Ashish Arora, Andrea Fosfuri, and Alfonso Gambardella. MIT Press, 2004.

- "Of Trolls, Davids, Goliaths, and Kings: Narratives and Evidence in the Litigation of High-Tech Patents," by Colleen Chien. North Carolina Law Review, Vol. 87 (2009).

- "On Corporate Governance: A Study of Proxy Contests," by Peter Dodd and Jerold B. Warner. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 11 (1983).

- "On Sharks, Trolls, and Their Patent Prey: Unrealistic Damage Awards and Firms' Strategies of 'Being Infringed'," by Markus Reitzig, Joachim Henkel, and Christopher Heath. Research Policy, Vol. 36 (2007).

- Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk, by James Bessen and Michael J. Meurer. Princeton University Press, 2008.

- "Patent Law, the Federal Circuit, and the Supreme Court: A Quiet Revolution," by Glynn S. Lunney, Jr. Supreme Court Economic Review, Vol. 11 (2004).

- "Patent Litigation with Endogenous Disputes," by James Bessen and Michael J. Meurer. American Economic Review, Vol. 96, No. 2 (2006).

- "Patent Quality and Settlement among Repeat Patent Litigants," by John R. Allison, Mark A. Lemley, and Joshua Walker. Georgetown Law Journal, Vol. 99 (2010).

- "Patent Thickets, Trolls, and Unproductive Entrepreneurship," by John L. Turner. Working paper, 2011.

- "Patent Troll Myths," by Michael Risch. Seton Hall Law Review, Vol. 42 (2012).

- "Patent Trolls and Technology Diffusion," by Catherine Tucker. Working paper, 2011.

- "Patent Trolls and the New Tort Reform: A Practitioner's Perspective," by Spencer Hosie. Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, Vol. 4 (2008).

- "Patent Trolls on Markets for Technology: An Empirical Analysis of Trolls' Patent Acquisitions," by Timo Fischer and Joachim Henkel. Working paper, 2011.

- "Patenting in the Shadow of Competitors," by Josh Lerner. Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 38, No. 2 (1995).

- "Patents, Licensing, and Market Structure in the Chemical Industry," by Ashish Arora. Research Policy, Vol. 26 (1997).

- "Stop Looking under the Bridge for Imaginary Creatures: A Comment Examining Who Really Deserves The Title 'Patent Troll'," by Marc Morgan. Federal Circuit Bar Journal, Vol. 17 (2008).

- "The Big Idea," by Nathan Myhrvold. Harvard Business Review, March 2010.

- "The Costs of Conflict Resolution and Financial Distress: Evidence from the Texaco-Pennzoil Litigation," by David Cutler and Lawrence Summers. RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 19 (1988).

- "The Costs of Inefficient Bargaining and Financial Distress: Evidence from Corporate Lawsuits," by Sanjai Bhagat, James A. Brickley, and Jeffrey L. Coles. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 35 (1994).

- "The Emerging Patent Marketplace," by Tomoya Yanagisawa and Dominique Guellec. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Directorate for Science, Technology, and Industry working paper, 2009.

- "The Myth of the Patent Troll: An Alternative View of the Function of Patent Dealers in an Idea Economy," by James F. McDonough, III. Emory Law Journal, Vol. 56 (2006).

- "The Patent Litigation Explosion," by James Bessen and Michael J. Meurer. Boston University School of Law Working Paper No. 05-18, 2005.

- "The Private Costs of Patent Litigation," James Bessen and Michael J. Meurer. Boston University School of Law Working Paper No. 07-08, 2007.

- "The Settlement of Patent Litigation," by Michael J. Meurer. RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 20, No. 1 (1989).

- "The Shareholder Wealth Implications of Corporate Lawsuits," by Sanjai Bhagat, John M. Bizjak, and Jeffrey L. Coles. Financial Management, Vol. 27 (1998).

- "The Value of U.S. Patents by Owner and Patent Characteristics," by James Bessen. Research Policy, Vol. 37 (2008).

- "Transaction Costs and Trolls: Strategic Behavior by Individual Inventors, Small Firms, and Entrepreneurs in Patent Litigation," by Gwendolyn G. Ball and Jay P. Kesan. Illinois Law and Economics Papers Series No. LE09-005, 2009.

- "Trolls or Market-Makers? An Empirical Analysis of Nonpracticing Entities," by Sannu K. Shrestha. Columbia Law Review, Vol. 110 (2011).

- "Using Daily Stock Returns: The Case of Event Studies," by Stephen J. Brown and Jerold B. Warner. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 14 (1985).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.