The term “Great Enrichment” is not a simple metaphor. According to Nobel-laureate economic historian Douglass North: “The process of sustained economic growth that historians believe began between 1750 and 1830 radically altered the manner and standard of living of Western men and women. … The Western world achieved a standard of living which had no counterpart in the past.”

Why did the Industrial Revolution and the Great Enrichment start in the West and not elsewhere, like Asia? At least among economists and economic historians, the generally accepted explanation is that only Western countries developed the social, political, and economic institutions, including private property rights, favorable to individual liberty and prosperity. The 18th century Enlightenment was an important “cultural” ingredient. In economic historian Deirdre McCloskey’s perspective, Western ideas allowed ordinary people to escape poverty and form a bourgeois middle class.

In a more elitist view than is usual in the classical liberal tradition, Spanish philosopher José Ortega noted that technological development in the West was accompanied by theoretical developments that made continuing progress possible. Ortega wrote:

China reached a high degree of technique without in the least suspecting the existence of physics. It is only modern European technique that has a scientific basis, from which it derives its special character, its possibility of limitless progress.

China has arguably been the best representative of Eastern culture over more than two millennia. Many believe that, around the 13th century, Chinese technology was more advanced than its Western counterpart. Technologies and products such as silk, gun powder, the magnetic compass, papermaking, movable type, and porcelain were first invented in China. However, because the institutional and cultural factors mentioned above were lacking, innovations could not launch a cumulative movement of economic progress allowing the common people to escape poverty.

Capitalism and enrichment / Anybody reading literature and testimonies from before the 19th century cannot but be impressed by the dire poverty of most people in most countries in that era. Some historians believe that the average standard of living started increasing slowly in the 16th century, but it was only in a few places (such as the Low Countries, comprised of modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) that a relatively prosperous middle class of merchants grew significantly. The establishment in that area of an efficient capital market by the end of the 16th century was especially momentous. North and Robert Paul Thomas note in their 1973 book The Rise of the Western World that the rate of interest on loans decreased from 20–30 percent at the beginning of the 16th century to 3 percent or less during the 17th.

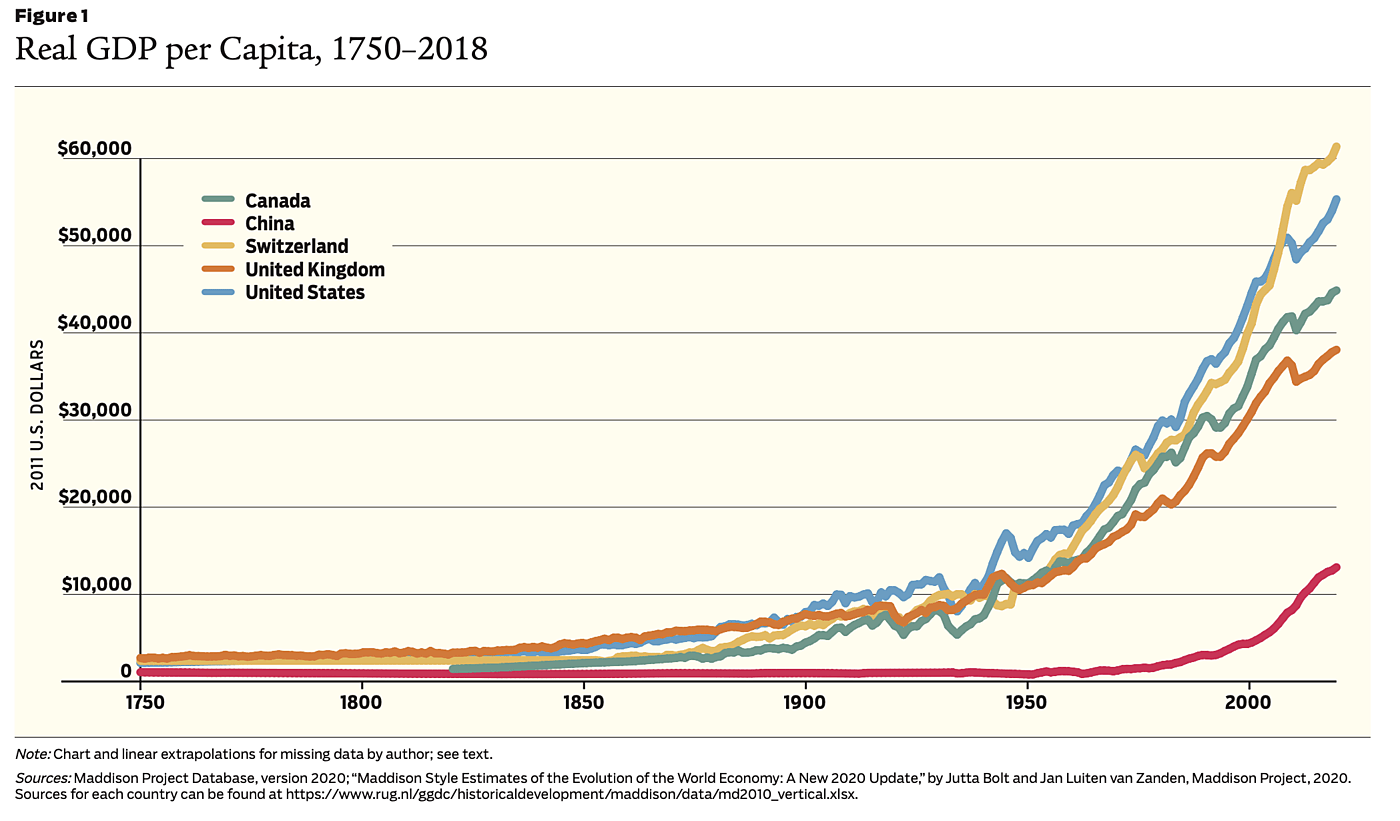

Figure 1 shows estimates of real gross domestic product per capita in a few Western countries and China since the mid-18th century. GDP per capita, equivalent to income per person, is the best measure of the average standard of living. The data, first assembled by Angus Maddison of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, go back to the year 1 AD. Except for a small increase starting around 1500, they show little or no increase in the standard of living. With the Great Enrichment, the standard of living soared—in the West.

A few explanations and caveats about these data must be kept in mind. Estimating GDP before its formal conception and construction in the 20th century must be done indirectly because of very partial historical records of prices and wages. The reliability of these estimates decreases as we move back in time. Following Maddison’s passing in 2010, scholars involved with the Maddison Project have carried on his work. The data underlying Figure 1 are from the latest update (2020) of the Maddison Project database. In the figure, I used linear extrapolations to fill in missing data, with gaps often extending for long periods.

It may be objected that quantified estimates of GDP far in the past are so uncertain as to be useless. No doubt, we should be prudent in using them. However, the broad tendencies shown by the Maddison Project are consistent with other forms of historical evidence and can provide a way to summarize what we know. Moreover, as Maddison himself suggested: “Quantification clarifies issues which qualitative analysis leaves fuzzy. It is more readily contestable and likely to be contested.”

The Maddison data from 1 AD onward suggest that the inhabitants of China and Western countries were more-or-less equally poor until the mid-18th century. But then, the West began to eclipse China. At the end of that century, real income per capita was more than three times higher in the United Kingdom than in China. In the 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution rolled on, the United Kingdom (along with the Netherlands, not included in the chart) moved ahead of China decisively. At the end of the 19th century, GDP per capita in the UK was nearly eight times that of China. In fact, China did not show serious signs of economic growth until the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. By that time, the factor of British economic superiority was nearly 13. By imitating Western technology and opening to international trade, China then started its own Industrial Revolution.

Trade and colonialism / As often noted, economic take-offs take less time as more-developed countries can be imitated and traded with. The poor benefit from trading with the rich—and vice versa, of course. The same happened among Western countries after the UK and Netherlands spearheaded the original Industrial Revolution. Figure 1 shows that countries like Canada and Switzerland rapidly followed and surpassed the UK in the middle of the 20th century. From the first estimate we have for American GDP per capita in the mid-17th century, we see the country following British growth and overtaking the mother country at the end of the 19th century.

The trajectories of the United States, Canada, and Switzerland illustrate the general fact that colonialism is not necessary for a country’s economic growth. British colonies likely did nothing to contribute to the metropole’s Industrial Revolution. On the contrary, Adam Smith argued in The Wealth of Nations that colonies cost British taxpayers more than the uncertain benefits that the exclusive trade imposed on them may have brought. British restrictions on the American colonies’ foreign trade retarded their growth. Protectionism is not conducive to economic growth.

The case of Spain, a major colonial empire from the 16th to the 19th century, is especially noteworthy. The metropole did not join the Industrial Revolution until after World War II. As North and Thomas note, “Despite the magnificence of their courts and their imperial ambitions, both France and Spain failed to keep pace with the Netherlands and England.”

By 2018, GDP per capita was still much higher in the UK than in China, but by a factor of “only” 2.9. That closing of the gap is partly due to the Chinese economy’s rapid growth in recent decades, and (it should be acknowledged) the UK economy has not been a model of Western growth in the past several decades. In 2018, U.S. GDP per capita was more than four times its Chinese equivalent. Viewed another way, the average Chinese citizen earns what the average American earned in 1941.

Openness, individual liberty, and institutions / The West became the West by being open to new ideas and to the world. In his 2016 book A Culture of Growth, Northwestern University economic historian Joel Mokyr notes “European willingness to adopt foreign techniques and products but also their total lack of coyness in doing so by explicitly naming products after their (supposed) origins,” like “chinaware” or simply “china.” (See “From the Republic of Letters to the Great Enrichment,” Summer 2018.) On its side, China was crippled by the imperial regime’s autarkic policies, as Stanford classicist Walter Scheidel argued in his 2019 book Escape from Rome, including bans on private foreign trade and the prohibition on construction and operation of large oceangoing ships. (See “Let’s Travel that Road Again,” Spring 2020.)

In contrast to Britain and continental Europe in 1750, Mokyr suggests that an Industrial Revolution was not in the cards for China:

A free and open market for ideas, such as emerged in Europe in the sixteenth century, leading eventually to the Enlightenment and a cultural transformation that created a new set of attitudes toward useful knowledge did not develop in China.

If it is true that the institutions and accompanying morals that developed in the West are a necessary condition for continued economic progress and for the general welfare of ordinary people, it would follow that efforts to maintain them are important. The maintenance of liberal institutions is a special challenge because they rest on an ideal of individual liberty, which can relatively easily be used by those intent to subvert it or ignorant enough not to care. (See “An Enlightenment Thinker,” Spring 2022.) But we should recognize the challenge and try to meet it.

Another implication relates to the developing countries in Asia and elsewhere. If the welfare of their inhabitants is to be served, those states should practice cultural appropriation and borrow from Western ideals and institutions. In the case of China, we should hope that its state will return to the opening that Deng Xiaoping encouraged following Mao’s death, instead of continuing Xi Jinping’s current backpedaling to authoritarianism. (See “Getting Rich Is Glorious,” Winter 2012–2013.) In the West, we should make sure that our own governments don’t intentionally hinder this process, nor embrace a similar backpedaling to pre-modern times.

Readings

- A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, by Joel Mokyr. Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World, by Deirdre Nansen McCloskey. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD, by Angus Maddison. Oxford University Press, 2007. Updates by the Maddison Project.

- Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity, by Walter Scheidel. Princeton University Press, 2019.

- The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History, by Douglass C. North and Robert Paul Thomas. Cambridge University Press, 1973.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.