Shop here and you could win your favorite brand-name item for up to 95 percent off retail prices!” boasts a standard advertisement for the penny auction industry. This attractive proposition sounds too good to be true, and for most customers it is. To offer that ostensibly great deal, penny auction websites like Beezid and Quibids charge every bidder—win or lose—a multiplicity of small transaction fees that can be sizeable in total. The fee structure resembles a lottery, which has raised concerns with regulators that penny auctions may be a form of gambling. Average revenues for the website far in excess of the value of the item have only increased scrutiny, given the seemingly raw deal offered to the average penny auction participant.

A typical penny auction works as follows: A valuable item is put up for auction at an attractive starting price. A countdown timer demarcates the tentative end point of the auction. A participant may press a button at any time to increase the auction price by a penny and become the high bidder. If he does so, the participant is then charged a nonrefundable bid fee, typically between 50¢ and $1. The fee is charged every time a bid is placed, and time is added to the clock if a bid is placed in the last few seconds of the auction. When time runs out, the high bidder wins the item and pays the end auction price (plus accrued transaction fees), which often is a fraction of the item’s value. Losing bidders likewise pay their transaction fees.

Regulation

To date, the penny auction industry is not subject to any special regulations, but it is subject to substantial regulatory uncertainty. The industry has recently drawn the attention of regulators such as the Federal Trade Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, the United Kingdom’s Office of Fair Trading, Connecticut’s Department of Consumer Protection, and Washington State’s Office of the Attorney General. Major penny auction websites have also been the subject of numerous private lawsuits, the outcome of which could potentially shape how the auctions are classified under existing law.

Criticisms of penny auctions can generally be grouped into three categories: accusations that the auctions are a form of illegal gambling, complaints about deceptive advertising practices, and allegations that certain websites utilize computerized shill bidders (i.e., fake auction participants that artificially increase prices). Concerning the latter two categories, deceptive advertising and known cases of shill bidding by some websites have given the industry a black eye, but those problems are not unique to the penny auction industry and can be dealt with largely through existing channels. For example, the Better Business Bureau tracks and rates the major industry players, several of which have earned high marks. The auction websites also submit to periodic third-party audits, in part to alleviate concerns about shill bidding. Consumers can file complaints with the Better Business Bureau or the Federal Trade Commission if they encounter unfair or illegal business practices. Both entities have issued warnings to consumers about penny auction scam websites. Furthermore, in the United States and the UK, shill bidders have been successfully sued for unlawful business practices and fraud.

Putting aside the concerns about deceptive practices and shill bidders, this article examines the question of whether penny auctions are a form of gambling and should be regulated as such. As part of that examination, I present the results of an economic experiment that tested whether the behavior of auction participants, rather than their proclivity to gamble, can explain high penny auction revenues. If behavior alone can explain the high revenues, then that suggests the auctions should not be regulated like gambling.

Illegal Gambling? The Case for and against

The legal definition of gambling requires the game in question to have a prize, chance, and consideration. Some laws also pertain to bets or wagers. Penny auctions clearly have a prize (the item) and consideration (the fees collected by the website); the debate centers around whether penny auctions involve chance, bets, or wagers. Opponents argue that bids in a penny auction constitute bets that no further bids will be placed. If winning a penny auction mainly requires chance rather than skill, then penny auctions could be classified as a form of illegal gambling.

To date, regulators and industry watchdogs have stopped short of explicitly mentioning gambling in reference to penny auctions, but the similarities have been pointed out in warnings issued to consumers. According to the Federal Trade Commission,

In many ways, a penny auction is more like a lottery than a traditional online auction. In a penny auction, you have to pay to bid. Before you know it, you could spend far more than you intended, with no guarantee that you’ll get anything in return.

According to the Better Business Bureau, “Unlike typical auctions, unsuccessfully bidding on an item through a penny auction will still cost you, and [the Better Business Bureau] has heard from people who lost thousands of dollars bidding on items and have nothing to show for it.”

U.S. courts have yet to establish a precedent regarding the classification of penny auctions. To date, all cases that allege gambling have either been settled or dismissed without explanation.

There is also debate in the academic community as to whether the high revenues of penny auctions are the result of inexperienced bidders who make systematic mistakes or are due to the potential appeal of the auction format to those who like to gamble. In a recent manuscript, Toomas Hinnosaar claims that

although penny auctions do not use any randomization devices, the equilibrium outcomes are still highly uncertain. Therefore from the individual bidder’s perspective, the auction format is similar to a lottery, which means that perhaps the definition of gambling must be extended to include auction formats like penny auctions.

Similarly, a recent paper in the journal Management Science by Brennan Platt, Joseph Price, and Henry Tappen claims:

[T]his auction is essentially a form of gambling. Like a slot machine, the bidder deposits a small fee to play, aspiring to a big payoff (of obtaining the item well below its value). The only difference is that the probabilities of winning are endogenously determined.

As I will show in this article, that line of thinking is fallacious, dangerous (insofar as it is used as a guide for policy), and unsupported by the evidence.

The problem with the above argument is that chance is fundamentally different from uncertainty. As Hinnosaar mentions, there is nothing inherently random about a penny auction. Given any set of actions, the outcome of a penny auction is entirely determined. The reason why a penny auction may seem random is that a participant does not know ahead of time what other participants will do. Furthermore, the lottery and slot machine analogies made in the above papers rely on the assumption that players use a very particular set of strategies—or, more accurately, every bidder uses the same strategy. If this were the case with penny auctions, then the stable outcome is for participants to bid at random times throughout the auction until one lucky individual wins the item. However, that sort of behavior is not generally observed in the penny auction data. One recent working paper by Joseph Goodman and another by Zhongmin Wang and Minbo Xu observe frequent bidding runs, i.e., long sequences of consecutive bids by a single auction participant, in field data. The likelihood that a pattern of random bidding would generate bidding runs of the frequencies and magnitudes observed in the data is vanishingly small.

Another problem is that even if some participants were to choose to bid randomly of their own volition, that in and of itself is not sufficient to qualify as gambling under existing law. Such a tactic is akin to a diner picking a random entrée off the menu at a restaurant that she has never been to before. There is a prize (the best entrée), consideration (the price of an entrée), and chance (the likelihood that she selects a particular entrée). She does not know ahead of time which entrée is the best. Yet this is not considered gambling because the chance is entirely manufactured by the diner. She could just as easily select any arbitrary entrée and receive an unknown, but entirely predetermined, benefit.

An Experiment

While the above argument clearly illustrates why penny auctions are not gambling as it is traditionally defined, that may only be of secondary importance to regulators. Instead, regulators may be concerned with whether penny auctions are psychologically addictive in a manner similar to gambling. It would be particularly damning for the industry if the same types of people who are attracted to gambling are also disproportionately attracted to penny auctions. For example, Platt et al. show that the observed field data are consistent with the assumption that penny auction participants like to gamble. However, there are many alternative explanations that are also consistent with the data and that have nothing to do with gambling.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to prove empirically that this is the case; to do so, we would have to track down a representative group of penny auction participants and measure their affinity for gambling relative to the rest of the population. However, a controlled experiment that I recently conducted does shed some light on this issue. In the experiment, individuals were recruited at random to participate in a series of penny auctions for cash prizes. Each individual’s affinity for gambling was then measured at the end of the experiment. If the experiment generated the observed revenues of penny auction websites with participants who like to gamble, then that would lend credence to the gambling argument. On the other hand, if the experiment generated the observed revenues of penny auctions with participants who do not like to gamble, it would be unlikely that gambling addiction is the driving force behind penny auction revenues. The experiment also tested the notion that chance predominates skill in a penny auction. If the auction outcomes in my experiment were seemingly random, then the argument could be made that it is as if penny auctions are a lottery. Alternatively, if auction outcomes differ systematically along some strategic dimension, then skill is a factor.

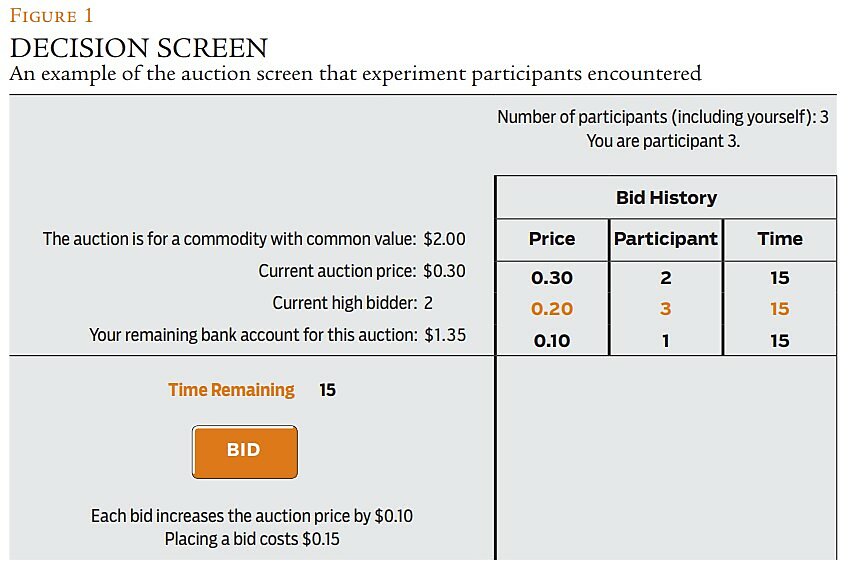

Design / My experiment was designed to closely replicate the format and interface of a typical penny auction. The user interface screen is depicted in Figure 1. Participants began each auction with $1.50 in their bank accounts, enough to cover any bid costs that may be incurred, and they bid on an item worth $2. A participant could press a button at any point in time to increase the auction price by 10¢ and become the high bidder. Taking that action cost the participant 15¢.

Those parameters were chosen so that the essential feature of penny auctions—that the bid fee is greater than the bid increment—was preserved, but the auctions could be conducted at an accelerated pace, taking no more than seven minutes rather than the typical hour(s) of online penny auctions. If no new bids were placed within 15 seconds after the previous bid, the last bidder won the item and paid the end auction price. Any remaining funds in the participant’s bank account were paid to the participant at the end of the experiment.

The experiment consisted of one practice auction and eight paid auctions in total, each conducted with a new, randomly assigned group. The number of participants (three or five) varied across experimental sessions. One additional parameter was varied across sessions and was found to have no effect. Discussion of that parameter is omitted from this article to avoid being overly technical. For more details of the experiment, I refer interested readers to my working paper, listed in the readings below.

At the end of the experiment, the participants chose to receive one of three (possibly random) bonus payments that differed in their average payment and risk. One paid $7 with certainty, another paid $10.25 or $4.25 with equal probability (which means the expected value was $7.25), and the third paid $12.25 or $0.25 with equal probability (expected value of $6.25). When multiple outcomes were possible, the participant was paid for one randomly selected outcome. The choice of payment was then used to divide participants into three categories: Participants who chose the first option exhibited an aversion to gambling; they were willing to accept a lower average payment to avoid the risk of the second option. Participants who chose the second option exhibited a willingness to gamble when it pays to do so; that option provided the highest average payment and was less risky than the third option. Participants who chose the third option exhibited a preference for gambling; they were willing to accept a lower average payment to increase risk relative to the other options.

On average, participants received approximately $20 for 80 minutes of their time, with payments ranging from $12.25 to $26.75.

Results

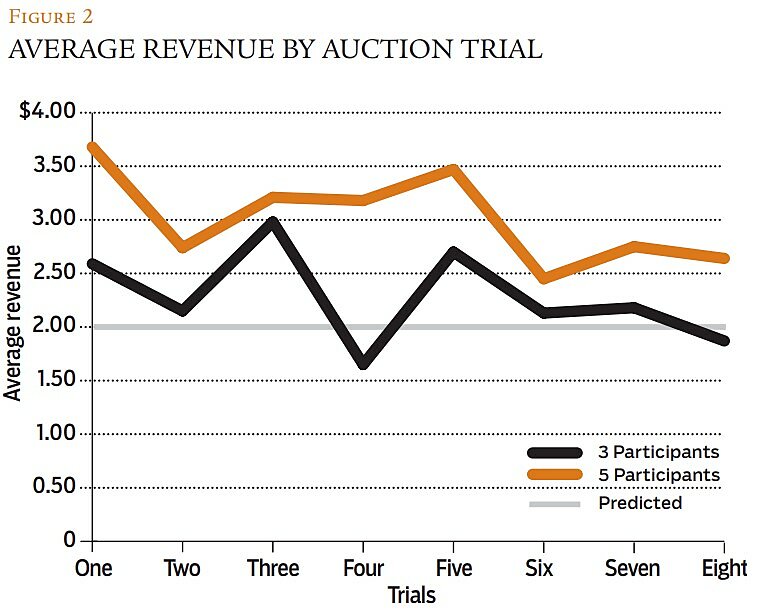

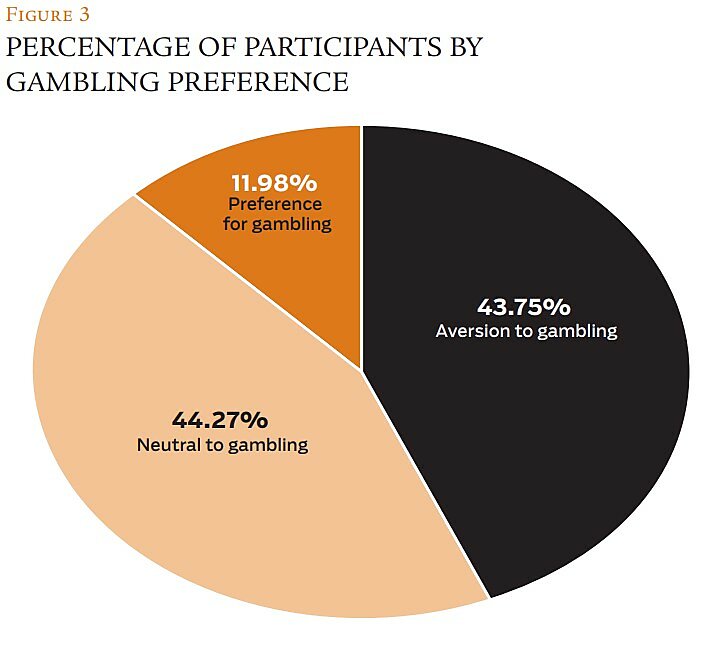

In general, the results from my experiment do not support the claim that high penny auction revenues are the result of gambling preferences. Figure 2 shows that average revenues start above, and largely stay above, the theoretical prediction for all treatments. Early auction revenues closely match the observed revenues of penny auction websites and slowly taper off over time, with the five-person auctions never converging to the predicted level. That is despite a pool of participants who are predominately averse to gambling. Figure 3 shows the fraction of participants who were classified into each category. Less than 12 percent of participants exhibited a preference for gambling, whereas almost 44 percent of participants exhibited an aversion to gambling.

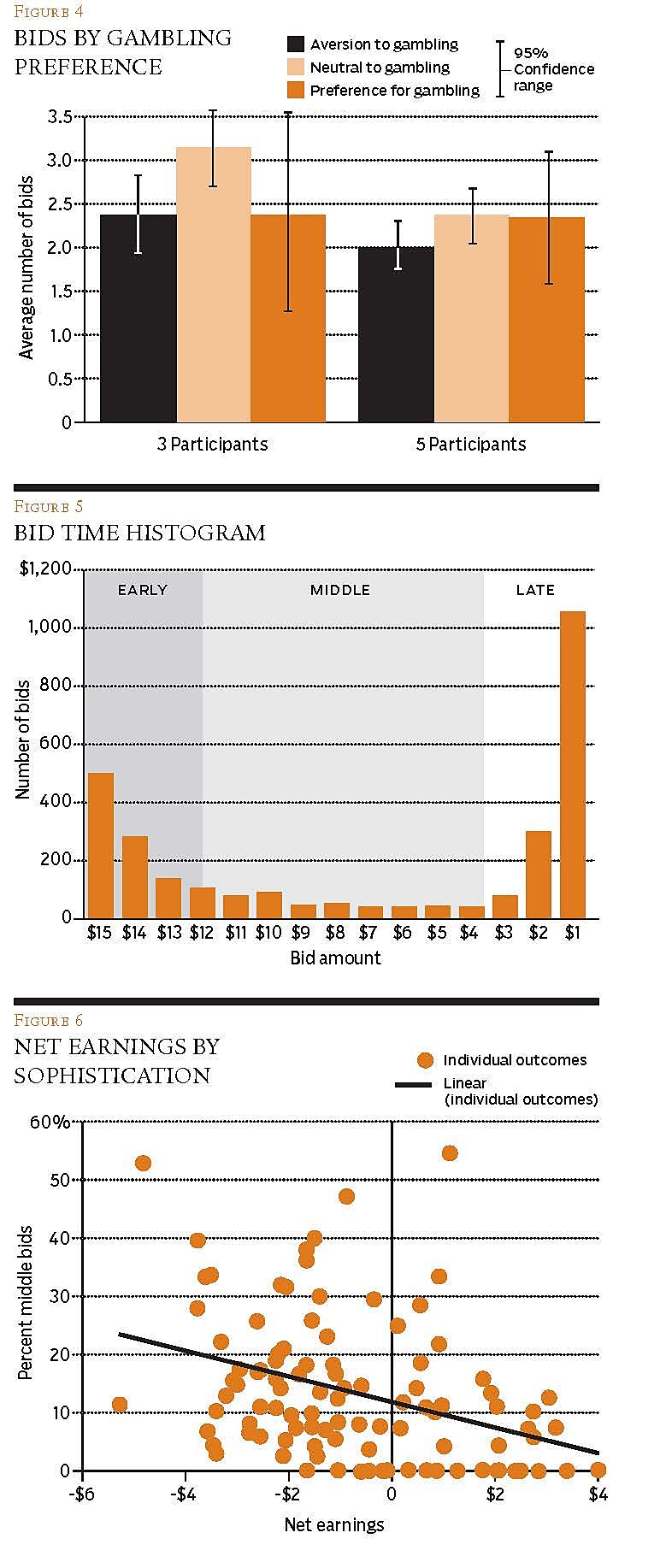

Figure 4 shows the average frequency of bids for each risk category. I do not find support for the hypothesis that people with a preference for gambling tend to bid more than others. If anything, the observed bid frequencies for individuals with a preference for gambling are lower than for the neutral group. However, the evidence is inconclusive because I do not have a sufficiently large sample of individuals with a preference for gambling to make strong statistical statements.

Following the method of Wang and Xu, I used the timing of bids as an indicator of strategic play. Wang and Xu view a participant who bid mostly at the beginning and end of the countdown clock as being more sophisticated than a participant who bid in the middle of the countdown clock. The gist of their argument for this idea is as follows: Often, waiting until the last second to bid is strategic because bids are costly and someone else may bid first. Occasionally, bidding early is strategic when it is advantageous to become the high bidder. It is never strategic to bid in the middle of the clock. Thus, I divided the bids in my experiment into three categories: early, middle, and late, based on the histogram shown in Figure 5. I classified bids placed in the first 3 seconds as “early,” bids in the next 8 seconds as “middle,” and bids in the last 4 seconds as “late.” In Figure 6, I plot each individual’s fraction of middle bids against that individual’s net earnings from participation. Individuals with a high fraction of middle bids (less strategic) tended to lose significantly more money than individuals with a low fraction of middle bids (more strategic). The most strategic individuals tended to win money or break even. This pattern clearly illustrates that skill is a significant factor in penny auction outcomes.

Conclusion

As the above analysis demonstrates, penny auctions do not violate existing gambling laws, do not rely on gamblers to generate high revenues, and are predominantly skill-based. Thus, calls to regulate penny auctions as a form of gambling are unwarranted.

For many consumers, penny auctions are not a particularly good deal; participants tend to pay more collectively than an item is worth. But penny auctions can also be a fun way to hunt for bargains on name-brand items. For some, the added fun may be worth the premium. A handful of participants are even able to systematically make money in penny auctions, as evidenced by many penny auctions setting caps on the number of items an individual can win in a given period.

The penny auction industry does seem to rely on the mistakes of new, inexperienced bidders to generate profits. Many of those bidders were likely drawn to the websites by the seemingly great deals that are offered. However, gimmicks are not illegal. We do not hear calls to regulate infomercials, get-rich-quick seminars, and fad diets.

The best tactic to help consumers avoid such gimmicks is to spread awareness. The Better Business Bureau already lists several practices to help avoid the worst the penny auction industry has to offer: check each website’s Better Business Bureau rating, read the fine print, know what you are buying and how much you are spending to get it. The Better Business Bureau adds that a prospective bidder should watch several auctions before joining in, and should think long and hard about whether participating is worth the time and effort. After watching hundreds of penny auctions, I can personally say that I prefer other business models for my own purchases.

Readings

- “A Penny for Your Auction: The Intersection of Purchasing and Gambling,” by Lawrence G. Walters. Working paper, Walters Law Group, 2013.

- “Attack of the ‘Bidbots,’ ” web-published by the Washington State Office of the Attorney General. 2013.

- “Be Cautious of Online Penny Auction Sites,” web-published by the Better Business Bureau. 2010.

- “Bidding Behavior in Pay-to-Bid Auctions: An Experimental Study,” by Michael Caldara. Working paper, University of California, Irvine, 2013.

- “Consumer and Producer Behavior in the Market for Penny Auctions: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis,” by Ned Augenblick. Working paper, University of California, Berkeley, 2012.

- “New CT Consumer Protection Commissioner’s Goal to Educate Consumers to Protect Themselves,” by George Gombossy. CTWatchdog.com, March 28, 2011.

- “OFT Tackles Fake Online Auction Bids,” web-published by the UK Office of Fair Trading. 2010.

- “Online Penny Auctions,” web-published by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. 2011.

- “Penny Auctions Are Unpredictable,” by Toomas Hinnosaar. Working paper, Northwestern University, 2013.

- “Reputations in Bidding Fee Auctions,” by Joseph Goodman. Working paper, Northeastern University, 2012.

- “SEC Shuts Down $600 Million Online Pyramid and Ponzi Scheme,” web-published by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2012.

- “Selling a Dollar for More than a Dollar? Evidence from Online Penny Auctions,” by Zhongmin Wang and Minbo Xu. Working paper, Northeastern University and Georgetown University, 2013.

- “The Role of Risk Preferences in Pay-to-Bid Auctions,” by Brennan Platt, Joseph Price, and Henry Tappen. Management Science, Vol. 59 (2013).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.