By American political standards, the new president of France elected last May 6 is a far-left politician. The Greek parliamentary election, held that same weekend, raised a challenge for the Greek bailout and budget austerity previously agreed on. These political convulsions are symptoms, but only symptoms, that something is deeply wrong in Europe. What is it?

The welfare state | The first factor, and usual suspect, is the size and cost of the European welfare state, but it must not be exaggerated. As I have argued previously (“A Welfare State by Any Other Name,” Spring 2012), both the United States and Europe are blessed with, or cursed by, a large welfare state, and it is only a bit worse and more ingrained on the eastern side of the Atlantic.

Yet, care must be taken not to fall into the opposite error of negating any difference in the relative weight of the welfare state in Europe and America. We must take with a grain of salt the argument, defended by economist Bruce Bartlett in his recent book The Benefit and the Burden, that a correct measure of the American welfare state should equate tax preferences (the Earned Income Tax Credit, the income tax deduction of mortgage interest, health insurance, etc.) with the direct transfers or central management preferred by European welfare states.

We can distinguish three ways to run a welfare state (or any interventionist state for that matter):

- The use of taxation to fund command-and-control social programs, as we see, for example, in the national education systems of some countries.

- The use of taxation to fund subsidies for beneficiaries, as we see, for example, in central-government grants to local schools, or school vouchers to parents.

- The use of “tax preferences” to encourage certain types of private spending, such as the American tax break given to employer-provided, or self-employed, health insurance.

Certainly the second and third alternatives are more efficient than the first because they give more choice to individuals and don’t require the central state to act on information that it cannot marshal (i.e., what do individual Americans need to improve their welfare?). Consequently, an American-style welfare state based on tax incentives is more efficient than a centralized welfare state, and the two should not be considered equivalent.

I would further argue—although this may be more controversial and require more discussion—that a tax-preferences system is often better than a taxes-and-subsidies system. Consider first an ethical, or distributive, argument: only if one agrees with Bartlett’s suggestion that taxes redistribute “the nation’s resources,” as opposed to the money of individuals, would one admit that tax preferences correspond to money that belongs to the state but that the latter graciously allows citizens to keep. There is a second, more economic Public Choice argument: if you admit that all “the nation’s resources” are for the state to dispose of as it wants, you are in for a lot of redistributive exploitation. In this perspective, even assuming that the deadweight loss of taxes is higher under a tax preferences system than a subsidies system, the former may be preferable. Loopholes may be useful, as Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan argued in their 1980 book The Power to Tax. This Public Choice approach provides another reason why we cannot give tax preferences the same weight as direct government intervention in measuring the welfare state.

More convincingly, analysts have argued that, on sensible measures, taxes are more progressive in the United States than in many, if not most, European countries. Casey Mulligan, Véronique de Rugy, and (in a way) Bartlett himself are among the latest proponents of this idea, which Maurice Cranston already defended three decades ago. This line of thought further suggests that the welfare state and its redistributive drive do not constitute the main difference between Europe and America.

Regulation | A second, more important factor is regulation. Although regulation and the welfare state naturally come together, the former is arguably more detrimental to liberty and prosperity than the latter. And Europe is very much under the yoke of regulation. Indexes of regulation by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development give the European Union a 50 percent higher score than the United States in its measure of economy-wide regulation, a 100 percent higher score in its measure of regulation of professional services, and a 400 percent higher score in the complexity of administrative procedures. The regulatory burden has not improved a great deal since the creation of the EU. National regulations of the labor market still hamper the free movement of labor. Moreover, national regulations have often been replaced by transnational regulation, making regulatory arbitrage more difficult.

Regulations hit labor markets especially hard. The OECD calculates an index of “employment protection” to measure restrictions on freedom of labor contracts and on the capacity to dismiss workers. All EU15 countries (the original members of the European Union) are more restrictive than the United States, and (with the exception of Ireland and the United Kingdom) more restrictive than Switzerland. Similarly, the most recent Economic Freedom of the World Index, produced by the Fraser Institute and the Cato Institute, shows economic freedom in the field of labor to be slightly higher in the United States than in Switzerland, while both countries leave the EU15 far behind.

Switzerland is an interesting case in many respects. It is a European country formally outside the EU, it has a welfare state, and yet its labor market is less regulated than Europe’s (it doesn’t have an official, centrally determined minimum wage, for example) and, in some ways, America’s.

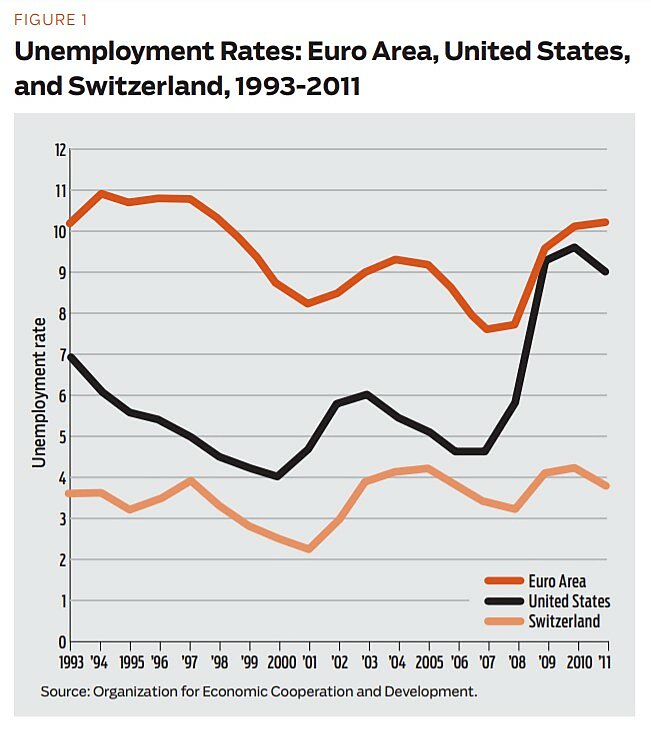

Labor market regulation is widely seen by economists as a major cause of labor market inflexibility and unemployment. The more difficult it is to dismiss employees, the more hesitant employers will be to hire a prospective worker in the first place. Indeed, when we compare unemployment rates with measures of “employment protection” or negative economic freedom in the labor market, the correlation is as expected: the more extensive the labor regulations, the higher the unemployment rate.

Figure 1 lends further support to this conclusion by comparing the evolution of unemployment in Euro-area countries, the United States, and Switzerland. Until the recent recession, the rate of unemployment fluctuated between 8 and 10 percent in the Euro area, which was twice the U.S. rate, while Swiss unemployment was 1 or 2 percentage points below America’s. The recession muddled the cards, as the U.S. rate has jumped close to European levels. However, the American economy is recuperating faster than the Euro area, and Switzerland has been barely affected by the surge in unemployment. Not shown on the figure is youth unemployment, now close to 50 percent in Spain and over 20–25 percent in several European countries.

The unemployment picture is not as neat since the recession. Until 2007, the prevalence of long-term unemployment (defined as the proportion of the unemployed without a job for one year or more) was at least four times higher in the EU15 than in the United States, but the gap had dropped to 45 percent by 2010 (the last year of comparative data). It is only in 2010 that the proportion of discouraged unemployed (those who are not seeking employment anymore) in the United States rose a bit over that in the EU15. The recession has been devastating for America, but the devastation had been in preparation for some time as the American economy became much more regulated. Especially notable are the cases of credit markets and general business regulation, where regulation is now often more restrictive in America than in Europe. The Europeanization of America has been advancing.

Bureaucracy | The third factor is the power of Europe’s government bureaucracy. European bureaucrats have highly protected jobs, even if that protection has weakened somewhat with the sovereign debt crises. They also form a large part of the population, including the voting population. In the typical core EU country, government employees (all levels, but excluding public corporations) make up 17 percent of the workforce, compared to 15 percent in the United States and 10 percent in Switzerland. Note again that America is close to, and merely not as bad as, Europe.

Perhaps more important is the day-to-day power of European bureaucrats, called “Eurocrats.” Through the non-elected European Commission, they exert much more power on the political structure of the EU than do their counterparts in the United States and Switzerland. The European Commission is the civil service of the EU, but it is also a regulator and it has the exclusive right to propose laws to the European Parliament. Eurocrats form a real aristocracy, insulated from their political masters and from the voters. As The Economist writes, “voters cannot throw out the bums in Brussels.”

Statism | The fourth factor is the fugacious phenomenon of ideology. Political traditions, the content of public debates, and the composition of political assemblies are less libertarian, more statist, in Europe than in the United States. So when Europeans want to express discontent with the traditional left and right—and they have ample reasons to do so—they have no alternative but voting for more of the same.

Not everything is wrong in Europe. Mores are more relaxed. The good life is good, if you don’t love individual liberty in areas where your government happens to hate it. The Surveillance State is now more constrained than in the United States—who would have imagined that two or three decades ago? Liberticidal laws are not always ferociously enforced. Low-level bureaucrats are less self-righteous and easier to challenge. Yet, by and large, and especially in the narrowly defined economic sphere, the answer to the question “What’s wrong with Europe?” is, “Everything that’s wrong in America, with a vengeance.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.