In The Americans: The Democratic Experience, historian Daniel Boorstin describes a set of remarkable people who shaped the economy during the 100 years following the U.S. Civil War. Those entrepreneurs, inventors, and innovators, whom Boorstin dubs “go-getters,” were in the vanguard of booming economic growth and development of the 20th century.

We believe that a similar group will likewise shape the 21st century United States. Where will these new go-getters locate? Will they move to areas where returns to investment in human capital are highest? Will they choose areas with lower taxes and less burdensome regulation? Will they seek greater personal freedom? Do go-getters who already live in the United States behave like those immigrating from abroad? To answer these questions, we examined domestic and immigrant migration patterns of young people in the prime years of their working lives, presumably the builders of future economies. We then seek to explain their migration decisions to the 50 states.

We discovered that emerging knowledge economies and high levels of economic freedom do indeed attract go-getters. Personal freedom and a creative environment are also important factors. Most consequential, however, is evidence that domestic and international migrants behave very differently when deciding where to locate in the United States. Young domestic movers appear to value economic freedom, diversity, and cultural environment most highly. Young international immigrants seem to seek emerging knowledge economies and high levels of personal freedom.

Based on our statistical findings, we offer inferences as to why the behaviors of the two groups differ. We also assess the relative weight of limited government as revealed by freedom indexes in determining migration decisions.

WHY DO THEY MOVE?

Researchers have studied migration patterns at length and hypothesized about the determinants of those patterns. Invariably, researchers seeking to model movers include arguments that relate to income, costs, and the benefits associated with alternative destinations. Charles Tiebout in 1962 expanded those considerations to include the public sector, arguing that people revealed their preferences for public goods and their associated socialized costs by “voting with their feet,” a topic that relates directly to economic growth and change.

Scholars have combined Tiebout’s seminal argument with more orthodox variables to model movement. But no one has used freedom indexes paired with knowledge economy indicators as principal determinants of migration patterns across the 50 states. Nor has anyone employed personal freedom indexes with freedom and knowledge indexes in an effort to decipher those patterns. Including those elements distinguishes our research.

Much recent economic research focuses on the emergence of a new knowledge sector that supposedly will serve as a strong foundation of economic growth. As this sector has become a crucial and large slice of the economy, researchers have developed indexes and rankings for cities, states, and countries that measure knowledge economy performance. Similarly, economic freedom indexes are now popular tools among economists and political scientists.

We argue that migrants carefully weigh benefits and costs of moving from one location to another. They evaluate typical economic benefits, such as income, as well as other factors that influence quality of life. For some, access to performing arts, vibrant cities, and cultural activities are as important as lower taxes and less oppressive regulation. Others may be more influenced by the availability of employment in high technology enterprises. To these arguments we add a third: migrants consider how much personal freedom they will have in competing locations and how they will be burdened and benefited by the government sector in their new location. All of these factors are considered by both domestic and international migrants.

International migrants, however, face a distinct set of constraints when considering a move from a home country to one of the U.S. states. There are visa requirements and security filters that limit movement. The foreign migrant’s “ticket price” to move to a state is higher on average than that of a domestic mover; therefore, the international mover is less sensitive to cost-of-living differences once in the domestic market. Living costs are a smaller share of the total cost of choosing one location versus another and can be offset by an increase in income, which is usually larger for foreign immigrants relative to domestic movers.

Foreigners also face more restrictive cultural constraints than domestic movers. Relatively drastic differences in language and culture make it likely that immigrants will not assign great importance to the types and quality of local music, food, and performing arts when choosing a location. To the recently arrived Pakistani, Ghanaian, or Ecuadorian; California, Iowa, and Virginia are all an extreme cultural shift from life at home. We believe immigrants assign less importance to intra‑U.S. factors than domestic movers. In this sense, the foreign mover is more footloose.

OUR STATISTICAL INVESTIGATION

We used a series of regression models to estimate go-getter immigration to the 50 states by domestic and foreign movers. We defined go-getters as people in the 25–39 year-old category and then used Census Bureau data to examine positive flows of this migrating group for the years 2004–2008. By definition, domestic movers relocate from one state to another; international movers move to a given state from abroad.

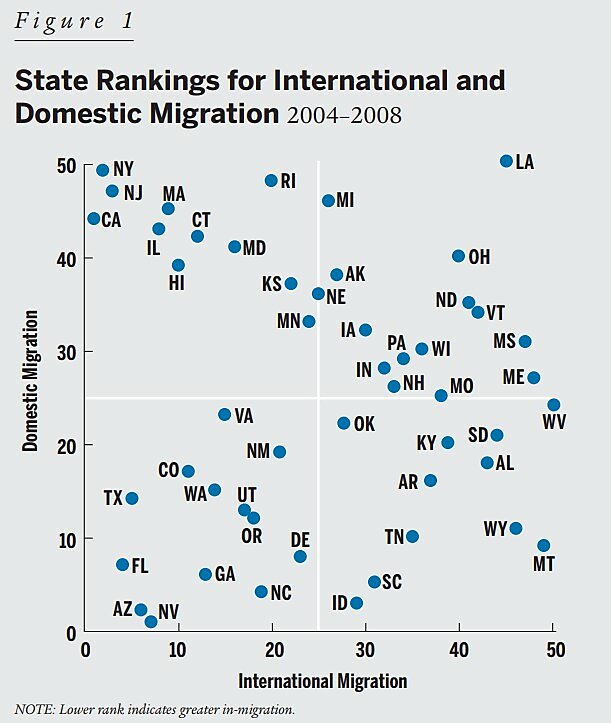

The scatter plot in Figure 1 maps state rankings for average net migration rates for the years 2004–2008 for domestic and foreign migration. We have divided the chart into four quadrants to identify the stronger and weaker migration patterns.

We note that foreign and domestic movers are flocking to states in the southwest quadrant of the chart, many of which are in the Sun Belt. Neither group is eagerly moving to states in the northeast quadrant. Lots of internationals are immigrating to highly populated states in the Northeast and to California, but domestic movers are fleeing. Other states seem to be insulated from foreign immigrants but are appealing to domestic movers.

H‑1B Visas Many foreign movers enter the United States under temporary visa programs. One such visa is the H‑1B, which allows highly skilled internationals to work in science and technology sectors for up to six years.

There is an annual cap on the number of laborers allowed under the program. The limit was 140,000 in the 1990s and increased to 195,000 for 2001–2003; it then fell to 65,000 in 2004 and remains at that level. To obtain workers under the program, potential employers must apply and pay a fee for each worker employed. The H‑1B program reduces the search cost for both employer and employee. Workers sponsored by or employed at academic institutions, nonprofit research organizations, and government research organizations do not count against the cap.

The relative merits of the H‑1B program, and others like it, are fiercely debated. Domestic labor interests generally strive to protect American workers from additional competition and oppose temporary worker programs. Other parties are concerned that increased restrictions encourage highly skilled foreign workers to seek employment in other countries. There is an additional concern that the best and brightest international students enter the United States to study at top research universities, only to return home upon graduation — the “reverse brain drain.”

Recent research, however, suggests that many immigrants choose to leave the United States for reasons unrelated to visa status. Some return home for a perceived better quality of life, to live in a familiar culture, or for increasingly better job opportunities abroad, many in China and India. Our analysis reveals that foreign immigrants who do enter the United States seek work in the emerging knowledge economy, and they desire high levels of personal freedom. States should consider these factors if they seek to quell or counter the reverse brain drain.

Indexes We used several indexes, along with other variables, to explain migration patterns in our regression models. Two of those indexes are the Knowledge Economy Index (KEI), which we developed, and the Mercatus Overall Freedom Index (OFI). We also later employed a component of the OFI, the Mercatus Personal Freedom Index.

The KEI assesses the relative effectiveness of each state’s knowledge economy, the sector of the economy in which value lies increasingly in ideas, services, information, technological innovation, and relationships. Included in the index is information on educational attainment, research and development, and entrepreneurship. The OFI has two underlying components: the Economic Freedom Index, which measures items such as government size and spending, and the Personal Freedom Index, which measures state paternalism that restricts activities such as alcohol consumption and Sunday retail sales.

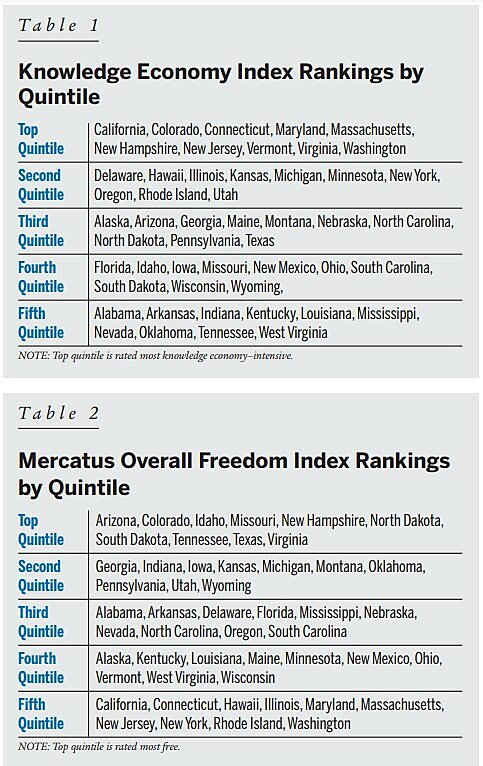

The KEI measures the performances of state knowledge economies by accounting for three components: knowledge, innovation, and entrepreneurship. It includes one indicator for each component. The first indicator is the weighted educational attainment of the workforce. Advanced degrees are weighted heavier than bachelor’s degrees, which are weighted heavier than attainment levels below college degrees. The second is private-sector spending on research and development, weighted by total worker earnings. The third is the relative number of fast-growth firms, which we identified using the Inc. 500 and Deloitte Technology Fast 500 reports. This last indicator is a knowledge economy “marker species” that signals high-knowledge production. Table 1 presents the 2008 KEI state rankings by quintile.

Northeastern states, California and the Pacific Northwest, Colorado, and the D.C. metro area states score highest on the KEI. Each of those states has concentrations of highly educated people and industry clusters based on services, technology, or science. On the other end of the spectrum, states in the South and Appalachia, as well as Indiana and Oklahoma, have weak knowledge economies.

The OFI measures freedom across the 50 states. William Ruger and Jason Sorens, the index creators, claim that their notion of freedom is grounded in individual rights: citizens should be allowed to act freely as long as they do not infringe upon the rights of others. The OFI uses 20 indicators grouped into three policy dimensions: fiscal, regulatory, and paternalism. The authors develop weights and statistical treatments to determine each indicator’s final score. Table 2 presents the OFI state rankings by quintile.

Interestingly, several of the top KEI states are among the lowest OFI states. California, Washington, and most Northeastern states have booming knowledge economies but extremely low levels of economic and personal freedom. However, Colorado, New Hampshire, and Virginia are in the top quintile of both the KEI and OFI.

Other Variables We used a variety of independent variables in addition to the KEI and OFI to estimate migration patterns. One is an updated version of Richard Florida’s state creativity index, which he first developed in his 2002 book The Rise of the Creative Class. The Florida index uses four types of data: creative class concentration, high-tech industry concentration, patents per capita, and a diversity index based on the share of a population that is gay. Per capita income is another variable included in our model. We also include a cost-of-living index published in 2009 by the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center. Average population for 2004–2008 is included as a control variable to adjust for scale.

THE RESULTS

Our resulting estimates for international migrants are strikingly different from the domestic migration estimates. The number of domestic movers to a given state is associated highly with overall freedom, economic freedom, and creativity. Of these, overall freedom is the dominant magnet.

Somewhat surprisingly, a robust knowledge economy does not appear to attract domestic migrants, but it is the main attractor for international movers. Apparently, the variables contained in the Knowledge Economy Index matter far more for international migrants than domestic movers. The statistical results confirm our assertion that foreign immigrants do not seek a specific creative or artistic environment, at least not when considering nuances of American culture. As measured by the creativity index, the cultural elements that significantly move domestic migrants have no effect on their international counterparts. Our results also show that international movers are not deterred by a high cost of living, possibly confirming our conjecture that the relatively high “ticket price” and the potential for increased wages make cost-of-living differences negligible. Per capita income is a statistically insignificant measure, which suggests that the other variables may proxy for income differences.

Personal Freedom We replaced the OFI with one of its components, the Mercatus Personal Freedom Index, to further examine the apparent differences between migration determinants of domestic and foreign movers. We then re-estimated our models. The PFI accounts for half of the OFI. The results were again different for the two groups, but in a different manner.

Domestic movers assign little importance to cross-state differences in personal freedom restrictions, while the estimate indicates that international movers assign great importance to avoiding such restrictions. The KEI was again highly associated with international movement. Our results indicate that international movers assign high values to knowledge economy opportunities and to personal freedom. Evidently the United States still beckons as a land of opportunity for foreign immigrants.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Our research has focused on the use of two state indexes to explain migration choices for go-getters, both domestic and foreign. We find that international immigrants respond positively to the Knowledge Economy Index and to overall freedom. Domestic movers are unaffected by the knowledge index but are attracted to overall freedom. The creativity index significantly affects the domestic set, but has no influence on foreign movers. We attribute this difference to the groups’ dissimilar cultural preferences.

Our work examined the association between personal freedom and state migration patterns. Here we found that international movers are sensitive to personal freedom; domestic movers are not. Domestic migrants are sensitive to the other components of the overall freedom index: fiscal and regulatory freedom. Our research suggests that knowledge economy and freedom indicators can explain what we have termed go-getter migration patterns, especially for international movers.

Go-getters will build and shape future economies. States with abundant freedom and a burgeoning knowledge sector will attract the go-getters.

Readings

- “A Pure Theory of Local Public Expenditures,” by Charles M. Tiebout. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 64 (1956).

- “America’s Loss Is the World’s Gain,” by Vivek Wadhwa, et al. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, March 2009.

- “Building a Knowledge Economy Index for Fifty States with a Focus on South Carolina,” by Tate Watkins. Clemson University Department of Economics M.A. Thesis, 2008.

- “Can Freedom and Knowledge Economy Indexes Explain Go-Getter Migration Patterns?” by Tate Watkins and Bruce Yandle. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, forthcoming, 2010.

- “Freedom in the 50 States,” by William P. Ruger and Jason Sorens. Mercatus Center at George Mason University, February 2009.

- The Americans: The Democratic Experience, by Daniel Boorstin. New York: Random House Publishers, 1974.

- The Rise of the Creative Class, by Richard Florida. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.