A February 2025 White House memorandum on “Reciprocal Trade and Tariffs” complained that other countries’ value added taxes (VATs) are “unfair, discriminatory, or extraterritorial taxes imposed by our trading partners on United States businesses, workers, and consumers.” President Trump has held this view since at least 2017, when he told The Economist: “Part of the problem with NAFTA is that Mexico’s a VAT. So Mexico is paying almost … we pay 17 per cent. So we are now down 17 per cent, going into Mexico when we trade.”

Many of Trump’s advisers and surrogates echo this view, which is widespread in American protectionist circles. Earlier this year, Jason Cummins of Brevin Howard Asset Management wrote in a Financial Times op-ed, “Officials have correctly identified that Europe’s competitive advantage primarily owes to non-tariff barriers—especially how it applies value added tax.” He proposed a 25 percent American tariff to compensate. And he did not forget the obligatory praise: “Trump has identified a genuine imbalance in trade with Europe that has vexed US policymakers for decades.” Among American politicians, these views on the VAT are not new; they have been promoted by politicians of both major parties since the 1970s.

However, it is not easy to find a reputable professional economist, wherever he stands on the American political spectrum—Martin Feldstein and Paul Krugman, for example—who accepts these unfounded and puzzling views. It is probably impossible to find an economist in the field of public finance who shares them. As Michael Keen (International Monetary Fund) and Stephen Smith (University College London) wrote in a 2006 National Tax Journal article, the VAT “does not amount to an export subsidy.” As we will see, it also is not an import tariff of the type Trump and his surrogates attribute to Mexico or Europe.

Those who believe a VAT is an import tariff or an export subsidy seem to misunderstand what this sort of tax is and how it works. In fact, a VAT is equivalent to a pure retail sales tax (one that does not hit inputs) in that it is paid by final consumers on the goods and services they buy. As a standard public finance textbook puts it, “A VAT is just an alternative method for collecting a retail sales tax” (Rosen and Gayer 2014, emphasis in original). A VAT is as different from a protectionist tariff or export subsidy as is a US state’s sales tax when someone purchases something in the United States.

What Is a VAT?

A VAT is a percentage tax charged to final domestic consumers within a given territory. A final consumer is a purchaser who resides in that territory and does not use the taxable good as an input in production. Although borne exclusively by the final consumer, the VAT is collected from businesses at each step of the production chain. It is collected on each business’s “value added” or addition to the value of the good—that is, roughly, on the business’s profits and labor costs for that good. An essential idea is that, though the business will remit (or be liable for) a tax payment on its value added, it will reimburse itself by adding that VAT to the purchase price of its output; that is, it will “pass forward” the VAT along the production chain. Only the final domestic consumer at the end of the chain pays the VAT, because there is no subsequent purchaser from whom to recoup it.

The VAT theoretically targets goods and services, although its application on intangible stuff is more difficult. Physical goods and individuals are easy to stop at borders, but their services (think of a translator online or a consultant) are more difficult to surveil, control, and tax. In economics, “goods” typically include services, but our illustrations here will deal with the simple case of tangible goods.

One recognized principle of taxation is neutrality with respect to the allocation of resources. As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) writes, “Business decisions should be motivated by economic rather than tax considerations” (OECD 2017). Not surprisingly, this does not always happen, even with VATs; politics impose imperfections. In Europe, many goods and services are exempt from the VAT or benefit from reduced rates, including 0 percent rates. Examples include basic foodstuffs (often reduced rates or zero-rated), education and health care services (generally exempt), and, in the United Kingdom, children’s car seats and certain domestic energy supplies.

A related taxation principle, internationally recognized, is the destination principle, which is structurally important in the VAT. It is, explains the OECD, a consumption tax that “is ultimately levied only on the final consumption that occurs within the taxing jurisdiction.” The two principles imply that goods, whether domestic or imported, are taxed where they are consumed, not where they are produced.

How It Works

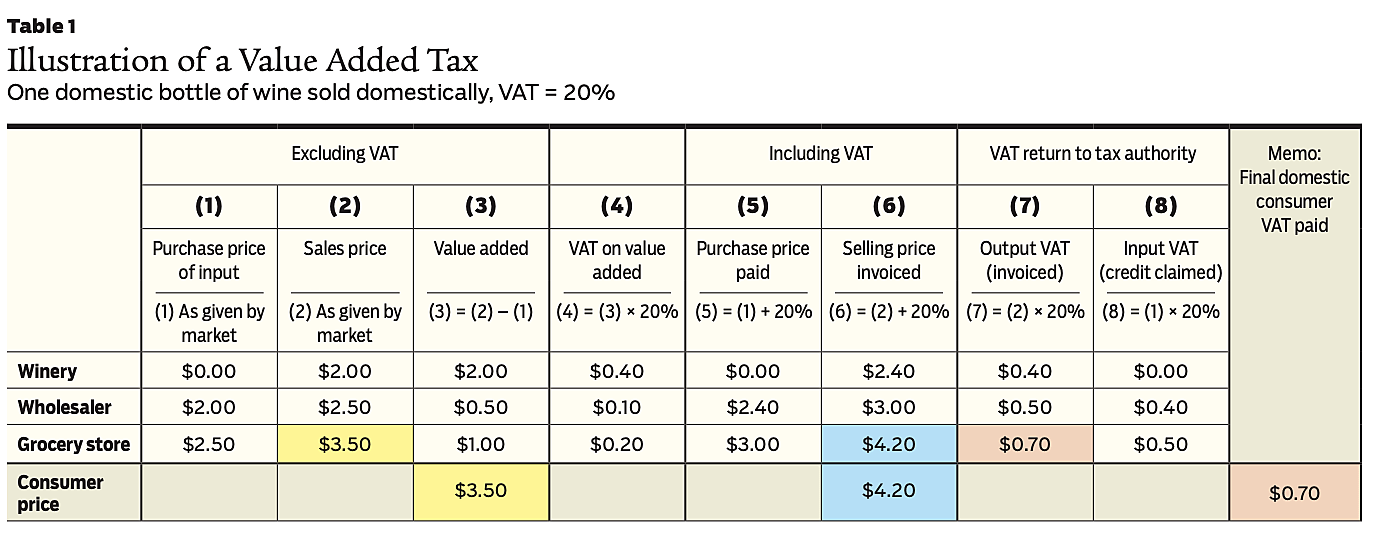

Let’s use the example of a bottle of wine to understand how a VAT works. (The numbers can be followed on Table 1.) Suppose the central government of the UK or a country in the European Union imposes a 20 percent VAT (a not atypical rate). Assume there are only three industrial sectors or stages of production in the wine industry: winery, wholesaler, and grocery store. Assume the market price of a bottle of wine of a given quality is $3.50 excluding the VAT. From the grocery store, the consumer purchases his bottle of wine for $4.20 VAT-inclusive—that is, for $3.50 VAT-exclusive plus a 70¢ VAT (20% × $3.50 = 70¢). Don’t attach any meaning to these figures (and the low price of wine!), except as far as the workings and consistency of the VAT system are concerned.

Now, let’s look carefully at each step along the production chain (summarized in Table 1).

The winery / At the first stage of production, let’s assume the winery is a self-sufficient family business that buys no inputs: Everything it needs is produced in-house, including tools and bottles. Its value added in the production of a bottle of wine is the VAT-exclusive price it is sold to the wholesaler—say, $2. Given the assumed 20 percent VAT, the winery sells the bottle for $2.40 including the VAT. It reports on its (monthly or quarterly) VAT return to its national tax authority a VAT of 40¢ for each bottle of wine it sells. This is called its output VAT because it is invoiced to its customer, which will be the wholesaler. The winery’s input VAT is the VAT paid on its inputs, which in this case is zero since we’ve assumed no inputs.

Since value added equals sales minus input cost, the VAT owed must equal the output VAT minus the input VAT. The winery thus must remit 40¢ for the bottle of wine to the tax authority. Except for its compliance costs, the winery is reimbursed its VAT cost by its customer, the wholesaler, whom it invoices a purchase price (VAT-inclusive) of $2.40. The winery has merely collected the 40¢ VAT on behalf of the government and passes it forward on the production chain. Its net monetary burden is nil: It pays no VAT. (Of course, the winery would not be happy with an increase of the VAT rate, which would raise the VAT-inclusive price of its wine and reduce quantity demanded, and it would be happy with a rate cut for the opposite reason.)

In Table 1, all these numbers—the $0 input cost, the $2 winery value added, the 40¢ tax on that value added, and the $2.40 purchase price to the next purchaser—all appear in the Winery row.

The wholesaler / The second stage of production is the wholesaler. Note that, in the economic sense, this merchant (like any other intermediary) is as much a producer as the winemaker: He adds value. If he did not, the grocery store that subsequently purchases the wine would bypass him and drive or fly to buy directly from the winemaker—or stock no wine at all.

Assume that market prices allow the wholesaler to resell the wine to the grocery store for $2.50 not counting the VAT. The wholesaler’s value added is 50¢, and the VAT (the tax on this value added) is 10¢ (50¢ × 20%). In his VAT return, the wholesaler declares an output VAT of 50¢ ($2.50 × 20%) and an input VAT of 40¢ ($2 × 20%). (We assume, for simplicity of exposition, that he or she buys no other input than the labor included in his value added.) Our wholesaler would thus have to remit 10¢ to his tax authority, which corresponds exactly to his own business VAT—that is, 20 percent of his value added. All these numbers appear in the Wholesaler row of Table 1.

It is important to understand that (like the winery before him and all producers) the wholesaler will be fully reimbursed by his customer for the VAT he owes to the government and for all other VATs he indirectly paid. The reason is that all his costs are included in the invoice he sends to the grocery store at the next stage of production. By paying the wholesaler’s VAT-inclusive price of $3, the grocery store will reimburse the former both the VAT of 10¢ on his value added and the VAT he paid on his inputs (40¢), for a total of 50¢.

This is what it means to “pass forward” the VAT along the production chain. This feature is arithmetically imbedded in the structure of a VAT. Every business at a given stage of production pays all the VAT collected and paid by its suppliers. The wholesaler gets reimbursed exactly as much from the VAT system as he contributes to it, and his net monetary burden is nil. At each stage of production, a business only collects the VAT for the government and ultimately pays no portion of it.

The grocery store / Let’s continue with the third and last stage of production in our simplified economy. The grocery store buys the bottle from the wholesaler for $2.50 VAT-exclusive and $3 VAT-inclusive. It sells the wine to the consumer for its previously assumed market price of $3.50 without VAT, which means for $4.20 VAT-inclusive (the $3.50 × 20% = 70¢). In practice, the VAT can be either incorporated in a VAT-inclusive price or as a separate line on the consumer’s receipt. The grocery store’s output VAT is 70¢ and its input VAT is 50¢ (incorporating all previous VATs passed forward), the difference being the VAT of 20¢ on its own value added. The reader should be able to trace all these numbers on the Grocery store line of Table 1.

The consumer / The highlighted panels of Table 1 are a reminder of the final consumer’s transaction: his purchase price without VAT ($3.50), the VAT he pays to the grocery store (70¢), and his VAT-inclusive price ($4.20).

But what happens to the 70¢ VAT the grocery store collects? The grocery store keeps it, reimbursing itself for both the input VAT of 50¢ it paid to the wholesaler and the 20¢ VAT it owes to its tax authority for its own value added. Like the other producers, the grocery store makes no profit from the VAT it collects from the consumer and bears none of the system’s financial burden. Only the final consumer at the end of the chain pays the whole 20 percent VAT on his retail purchase. This is not surprising because the VAT is a retail consumption tax.

Who Collects and Who Pays a VAT?

If businesses don’t pay any VAT on net, and the last producer (the retailer) keeps all the VAT it collects, how does the taxman get his money from the consumption tax? The answer, as we see in the discussion above and in Table 1, is that each business does send a VAT check to its tax authority in proportion (20 percent in our illustration) to its own value added, but it is reimbursed by passing this tax forward via its VAT-inclusive invoice price. The remitted amounts by businesses at each stage of production (40¢, 10¢, and 20¢ per bottle of wine, respectively) are included in the cost base of the last firm in the chain as input VAT.

By the time the grocery store sells the bottle of wine, all the accumulated VAT payments are embedded in its cost. The grocery store simply reimburses itself for these accumulated taxes by keeping the consumer’s VAT paid at the register. In a similar way, producers have collected the VAT along the production chain and been reimbursed by passing it forward to the next node, up to and including the consumer. It is no coincidence that the final VAT of 70¢ is equal to 20% of the total value added shown in column 3 of Table 1 ($2 + 50¢ + $1 = $3.50) because a VAT-exclusive price is nothing but the sum of all values added along the production chain.

Trump’s confusion / In his 2017 interview with The Economist, just before what I quoted above, Trump showed that he did not understand any of this. He declared:

I own Turnberry in Scotland. And every time I pay [the VAT] they say, “Yes sir, you pay it now but you get it back next year.” I said, “What kind of tax is this, I like this tax.” But the VAT is—I like it, I like it a lot, in a lot of ways. I don’t mean because of, you know, getting it back, you don’t get all of it back, but you get a lot of it back.

As we have seen, businesses ultimately don’t pay any of the VAT. They do “get all of it back” by passing forward whatever they owe (and, incidentally, they usually do not have to wait a year for that). What Trump passed forward to downstream purchasers was not only his British VAT, but also his ignorance to his supporters and allied officials.

The So-Called Border Adjustment

How can the VAT—a domestic tax paid only by domestic consumers—play a protectionist function while straight sales taxes do not? The answer is that it cannot.

Some problems do appear when foreign exports or imports break the tight chain of VAT calculations. The paradigmatic case is between a country with a VAT—e.g., Mexico, Canada, or a European country—and a country without a VAT, such as the United States. (The United States is the only OECD country without a VAT.) As we have seen, American protectionists argue that the VAT system, along with its border adjustments, has the same effects as a tariff on American goods imported into Europe, and a subsidy on European goods exported to America. Are they right?

The border adjustments in question may deceptively look like a special VAT imposed on imports in Europe and a VAT rebate for European exporters. But now that we understand how a VAT works, we can understand that the current border adjustments are required. The principles of destination and neutrality, explained above, require the current so-called border adjustments for a VAT country’s commerce with a non-VAT country, because all and only the VAT country’s residents are subject to the tax. Let’s see how this works.

Business imports from Europe / Consider an American wholesaler who wants to import wine from our European winery. Absent government restrictions and transportation costs, the European wine will sell at the same price as wine of the same quality made in, say, Oregon. This is in accordance with the “law of one price”: Identical goods should sell for the same price (before sales tax or VAT) when there are no transportation costs or trade barriers. If the prices differed, arbitragers would buy the wine from the low-price country and resell it in the high-price country until the prices are equalized, at $2 in our example. Here as elsewhere, we ignore other government interventions as well as transportation costs in order to focus on the effects of the VAT and its accompanying border adjustments.

If the European winery’s exports were subjected to the VAT, it would be outcompeted by wineries in Oregon. Collecting 40¢ per bottle in VAT on behalf of its tax authority, the European winery could not pass that expense forward to the American wholesaler, who would simply choose to buy a $2 bottle of wine from an Oregon winery. It would be like a special export tax of 40¢ per bottle had been imposed by the European authority on every exported bottle of wine. This problem comes from the nature of the VAT, which is a consumption tax to be paid only by the final domestic consumer but collected by businesses and pushed forward in the chain of production. A border adjustment solves this problem.

Exports are “zero-rated” in a VAT system—meaning the rate of VAT levied on them is 0 percent—because of the destination principle: Goods consumed in a foreign country are not subject to any tax authority except that of its own government. On his VAT return, the European exporter zero-rates the exported bottle. The output VAT of 40¢ that he would otherwise have to pay is zero. The American wholesaler will pay $2 a bottle to the European winery, and everybody is happy. The customer of the American wholesaler or the customer of his customer will have to pay his own state’s sales tax (as most American states impose a sales tax).

The border adjustment is not an export subsidy but rather the non-application of the collection of a domestic (European) tax meant to be passed on to the European wholesaler and ultimately to the European consumer. “Border adjustment” is not a well-chosen name: It has nothing to do with the border and everything to do with the domestic VAT regime. It is simply the reimbursement of a tax that is not to be collected on a good that is exported to a place with a different tax authority.

If the collected VAT were not refunded to the European winery, this business would be subjected to the equivalent of an export tax of 40¢—that is, a non-neutral and discriminatory tax targeting only exports and not domestically consumed goods. In our simple example, the export tax would be prohibitive and would prevent the European winery from exporting its wine.

Consumer imports from Europe / To give another example, suppose that an American consumer orders wine from the European grocery store’s website. The grocer sells the wine for $3.50 a bottle and zero-rates the export, but in the VAT system he can still be reimbursed the input VAT of 50¢ per bottle. Recall that this input VAT is the VAT paid to the wholesaler, which includes the VAT passed forward by the winery. On an exported bottle, the grocery store will be unable to recoup the collected VAT from the consumer because he is not a European consumer.

The border adjustment simply consists in the European tax authority reimbursing or crediting the grocery store for the tax collection along the production chain that should not have happened because there is no final domestic consumer. Hence, the so-called border adjustment is not an export subsidy but simply the cancellation of a tax the grocery store should not have had to pay. Without the adjustment, a de facto export tax of 50¢ on every exported wine bottle would be imposed on the European grocery store by its own government.

In short, the absence of the European VAT on exports to the United States is not an export subsidy because the tax is only to be assessed on European consumers. We can compare this to a US state’s sales tax not being applied to a good exported to a foreign consumer—or to a neighboring state for that matter. In the latter case, too, the non-taxation of the good is not an export subsidy but rather reflects the fact that the (non-walk-in) customer who buys the good is not subject to the other US state’s sales tax.

Not An Import Tariff

American protectionists offer a similar, and similarly invalid, criticism of the VAT: When a European imports a good from America, he must pay a European VAT. This, they claim, is a hidden import tariff. Let’s see why this claim is invalid.

American export to VAT consumer / Consider what happens if an (online) American grocery store exports a bottle of wine to a European consumer. Ignoring transportation costs and assuming the market is relatively free, the law of one price dictates that wine of the same quality as that depicted in Table 1 would carry an international retail price of $3.50 a bottle. When the American bottle arrives in Europe, the European consumer must pay the standard VAT rate that Europeans pay on wine produced in Europe. Assuming a VAT of 20 percent, the VAT is 70¢ and the purchase price of the American wine is $4.20, just like the same-quality European wine. Before the European consumer can put his hands on his purchase, he must pay the 70¢ VAT, just as if the wine had been produced domestically and sold at a VAT-inclusive price of $4.20.

This mimics how a national or state retail sales tax is applied when an imported good arrives. An American consumer must normally pay his state’s sales tax on what he imports from abroad or from another state; it is often not enforced on goods a walk-in customer purchases out of state, but it is for online purchases or purchases through commercial intermediaries.

With the European border adjustment, the consumer who resides there pays the VAT that he is legally obligated to pay as a retail consumption tax. Criticizing that is like if the EU or British government were to criticize American states for imposing a sales tax on imported European products. The border adjustment guarantees that the destination and neutrality principles are respected in international trade. It preserves the integrity of the VAT system without any effect on international competition and the allocation of resources.

The border adjustment may look like a customs tariff, but it is not—even if it may be administered by the customs office. It merely enforces a consumption sales tax meant to be paid on any good consumed by the residents of a certain territory.

American export to VAT business / The import of an input in Europe (or any country with a VAT) works the same way, albeit in a more indirect manner. Imagine that our European wholesaler imports wine from an American winery. For wine of the same quality as our European bottle and with our usual assumptions, the international VAT-exclusive price at the American winery’s gate must be $2 a bottle, the same as our European wine. The border adjustment by the European taxman consists in charging the importing wholesaler the same 40¢ VAT collection that he would have been subjected to had he purchased the wine from the European winery. As with the European bottle, the importing European wholesaler can reclaim the 40¢ as an input VAT on the American bottle, keeping his burden at zero.

The American winery has sold its wine at its usual price of $2, the standard VAT collection has been made (at the European border), the American wine will sell at European groceries for $3.50 a bottle excluding the VAT, and the European consumer will pay a VAT of 70¢, just as he would pay for the domestic wine. Charging the border adjustment to the importer has simply been a way to introduce the imported wine into the European chain of production with no disadvantage to the importer over and above what a fellow domestic producer experiences and with no discrimination against the exporter.

The only inconvenience for the American wholesaler-exporter is the same as for all European wine producers: The addition of the VAT reduces, without discrimination, the quantity demanded of their product. The destination principle, according to which consumption taxes are paid where the goods are consumed, and the neutrality principle, whereby domestic taxes are applied equally to foreign and domestic products, are both respected.

Another way to see how the neutrality principle is realized through this “border adjustment” is to look at what would happen without it. If the American winemaker could sell the European wholesaler a bottle of wine for $2 without the European taxman collecting the accumulated VAT, the effect would be the same as a European import subsidy of 40¢. Not charging the VAT on imports would arbitrarily favor American exporters, which could enter the European production chain without reimbursing the VAT collected upstream. European producers would be discriminated against by this indirect import subsidy.

Suppose now, for the sake of the argument, that the VAT border adjustments are, in reality, an export subsidy in one direction and an import tariff in the other, or that some imperfect implementation of the system leads to a similar but attenuated effect. It remains true that, after a time, the effects on trade would be nil or at least much reduced. As Bray et al. (2025) note, “A border adjusted tax leads to currency appreciation for the imposing country, which would make it cheaper to import goods, more expensive to export goods, and thus would cancel out the apparent benefits of the tax on imports and the rebate on exports.”

Anatomy of a False Problem

To summarize, the process whereby a VAT system adds its standard tax to imported goods and excludes it from exported goods has nothing to do with tariffing imports or subsidizing exports. The VAT is not protectionist, and its border adjustments are not disguised trade barriers. The opposite is true: The so-called “border adjustments” avoid what would otherwise be subsidizing the VAT-country’s importers and penalizing its exporters. Not making the adjustments would be like if a US state reduced its sales tax on goods imported from other states, or if one of the few American states with no sales tax created a special one on exports to other states.

A VAT is equivalent to a domestic retail consumption tax that is not meant to (and cannot) be charged to foreigners. A tariff is also a consumption tax, but it discriminates against imported goods. A VAT does not discriminate between imported and domestically produced goods and does not hit inputs. The typical “border adjustments” in VAT-countries are precisely meant to keep this tax non-discriminatory. They simply apply to imported goods the same tax collection mechanism that is applied to domestically produced goods. Does the VAT create an uneven playing field? “No. No way. Not at all,” says Brian Albrecht, chief economist of the International Center for Law & Economics (Albrecht 2025). Of course, the imperfect implementation of a neutral system can always cause some distortions. And we may add that “uneven playing fields” are everywhere in social and economic life, and it should be sufficient that the state does not intentionally create them.

So, why do protectionists proclaim the contrary? Why has the current American presidential administration, even more than preceding ones, professed demonstrably false claims on this topic? The charitable explanation is that the politicians don’t understand how a VAT works. But why doesn’t the White House have or consult informed economists who can explain to them what is happening? A less charitable explanation is that presenting the VAT as a barrier to trade conveniently stirs the nationalistic passions of voters and comforts politicians’ intuition that trade should not be left to the individual liberty of importers and exporters.

Readings

- Albrecht, Brian, 2025, “Stop Saying a Value-Added Tax Is an Export Subsidy,” Truth on the Market (Substack), March 27.

- Bray, Sean, Jared Walczac, and Erica York, 2015, “The European VAT Is Not a Discriminatory Tax Against US Exports,” Tax Foundation, February 12.

- Cummins, Jason, 2025, “A 25% Tariff on Europe Is Only Fair,” Financial Times, March 26.

- EU (European Union), 2006, Council Directive 2006/112/EC on the Common System of Value Added Tax, November.

- Keen, Michael, and Stephen Smith, 2006, “VAT Fraud and Evasion: What Do We Know and What Can Be Done?” National Tax Journal 59–4, December.

- OECD (Organisation for European Co-operation and Development), 2017, International VAT/GST Guidelines, Paris.

- Rosen, Harvey S., and Ted Gayer, 2014, Public Finance, 10th ed., McGraw–Hill.

- The Economist, 2017, “Transcript: Interview with Donald Trump,” May 11.

- UK Government, 2023, VAT Guide (VAT Notice 700), HM Revenue & Customs, last updated September 23.

Advantages and Drawbacks of a VAT

The VAT is a consumption tax that is entirely paid by the final consumer, but many economists claim it is preferable to a straight sales tax. Why?

One advantage is that a VAT is conceived not to distort, or distort as little as possible, the market allocation of resources, which works with relative prices. The VAT is designed to lift all prices in the same proportion, whereas sales taxes have no such built-in goal as they can also hit inputs besides final consumer prices. (Of course, politicians can mangle the VAT with exceptions, because they have done.) A related advantage is that, with its accompanying border adjustments, a VAT does not discriminate between imported and domestically produced goods, which are taxed at the same rate.

Another advantage is that a VAT avoids the frequent cascading or “pyramiding” of sales taxes as they are applied to some intermediate inputs and not reimbursed before hitting the final consumer at the cash register. According to Bray et al. (2015), “More than 40 percent of US sales tax revenues comes from intermediate transactions, which impose costs on US producers.” This is a handicap for American exporters even in interstate commerce. In the VAT system, exporters pay no VAT on inputs, so there can be no pyramiding.

A further advantage, some argue, is that enforcing compliance for a VAT may be less costly for the government compared to a sales tax. Businesses collect the VAT and, to a certain extent, self-police themselves in doing so. The incentive to avoid paying it is attenuated because a business gets fully reimbursed for any VAT payments it makes. It is well known, though, that a firm may be tempted to claim reimbursement for an input VAT that the firm, in fact, did not incur.

A VAT does have some drawbacks. The elaborate VAT system requires much regulation and bureaucratic surveillance. A quick look at the 242 pdf-equivalent pages of the online EU VAT Directive or the 162 pdf-equivalent pages of the online basic British VAT Guide (which features hyperlinks to several other guides) should persuade one that the administrative and compliance costs for businesses are high, notably for small businesses.

If we live in a society that is already too taxed and regulated, a new and more easily enforceable tax may be the last thing we need. By increasing government revenues and thus fueling more government spending and intervention, a VAT can generate economic costs that overwhelm any reduction in narrowly defined deadweight losses.

The minimum standard or default VAT rate in Europe is fixed at 15 percent, but many national governments go over that and many goods and services benefit from reduced rates or exemptions. The estimated proportion of VAT revenues in EU members’ government expenditures is 16 percent; in the US, the proportion of general sales taxes (the Census Bureau’s “National Totals of State and Local Tax Revenue: T09 General Sales and Gross Receipts Taxes for the United States”) is less than half of that (data for 2023). These numbers give us an indication of the tax potential of the VAT, either to replace other taxes or, more dangerously, to add to them.

The desirability of introducing a federal VAT system in the United States is thus highly debatable, to say the least. Unfortunately, the accelerating growth of federal deficits and debt provides a good and perhaps irresistible excuse to do so. It would likely add to America’s fiscal burden and push it closer to Europe’s.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.