How does one assess a new president in terms of regulatory activity? This question is difficult to answer at the beginning of a term because so many variables are in play: those in charge of regulatory agencies must be nominated and confirmed by the Senate, administration policies must be internally formulated and prioritized, and new and existing regulations must be written or modified.

But at some point, often 12–18 months in office, a president’s regulatory proclivities become clear. With that in mind, now is an appropriate time to take stock of Joe Biden’s administration.

Regulatory Output

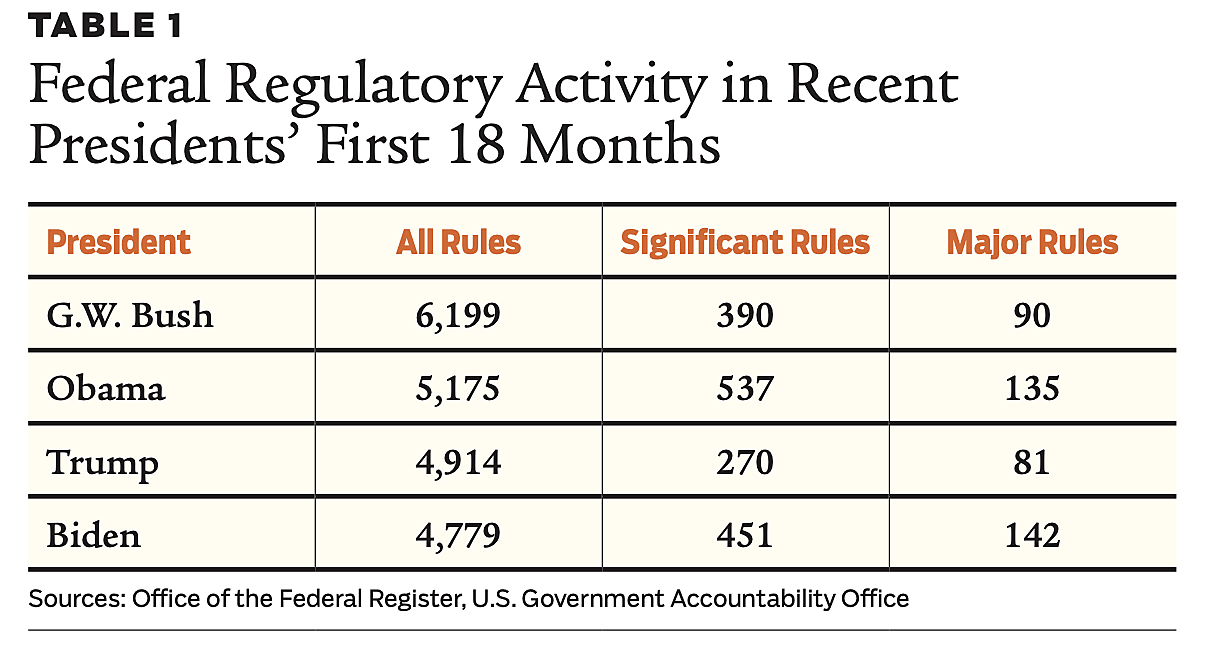

We can assess regulatory activity by comparison, counting the number of rules issued by a new president during his first few months in office. This requires some care; an aggregate total count does not reveal much because most federal rules are relatively minor and noncontroversial and do not reflect a president’s priorities. Instead, we count the important rules, those subject to White House review through the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). These rules, also known as “significant” rules, represent a small subset of new regulations, between 5% and 10% of all rules. Even more consequential are the smaller subset of “major” rules, those (1) having an annual effect (positive or negative) on the economy of $100 million or more (also known as economically significant rules); (2) imposing a major increase in costs or prices; or (3) having a significant adverse effect on competition, employment, investment, productivity, innovation, or international competitiveness.

Table 1 compares the number of rules by type issued under Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Biden during their first 18 months in office. According to the table, the total number of rules is trending down across presidential administrations. Although this may seem noteworthy, it doesn’t differentiate presidential administrations from each other and, more importantly, it doesn’t equate with regulatory burden. For example, the size of the Code of Federal Regulations—a compendium of all federal regulations and a good surrogate for aggregate burden—increases year after year and across presidential administrations. Debuting in 1938 as a handful of volumes, it has steadily expanded to consist of roughly 200 volumes.

For significant rules—the important rules—Biden lags Obama but both are well ahead of the pace set by Bush and Trump at this point in their presidencies. It is not surprising that the two Democratic presidents are more likely to use regulation to implement policy preferences than the two Republican presidents. It is also not surprising that the fewest significant rules occurred under Trump, a self-proclaimed proponent of deregulation who instituted a regulatory budget requiring agencies to eliminate two regulations for every new one. (See “Deregulation Under Trump,” Summer 2020.) That policy innovation, established through a Trump executive order, was eliminated by one of Biden’s first executive orders.

Biden, however, doesn’t take a back seat to Obama when it comes to major rules. Biden has issued seven more in his first 18 months. This is a mild surprise because Obama had set a record for issuing the most major rules (and most costly major rules) during his tenure.

Comparing Biden to Obama

At this point, one might suspect Biden’s regulatory activity is simply mirroring that of Obama. This wouldn’t come as a surprise to some experienced regulatory observers. Previously in these pages, Sam Batkins predicted that “the Biden legacy, at least after four years, will look like Obama’s.” (See “The Biden Regulatory Agenda,” Spring 2022.)

Or will it? To probe this question at greater depth, we can look at how the Biden administration (specifically his OMB) is reviewing significant rules. OMB review has two purposes: to identify and address issues arising from interagency review, and to ensure regulations comport with best practices and maximize net benefits based on cost–benefit analysis. We can look at the number of rules and notices that OMB has concluded review on after 18 months in office. If Biden is mirroring Obama, OMB output should be similar in quantity and quality.

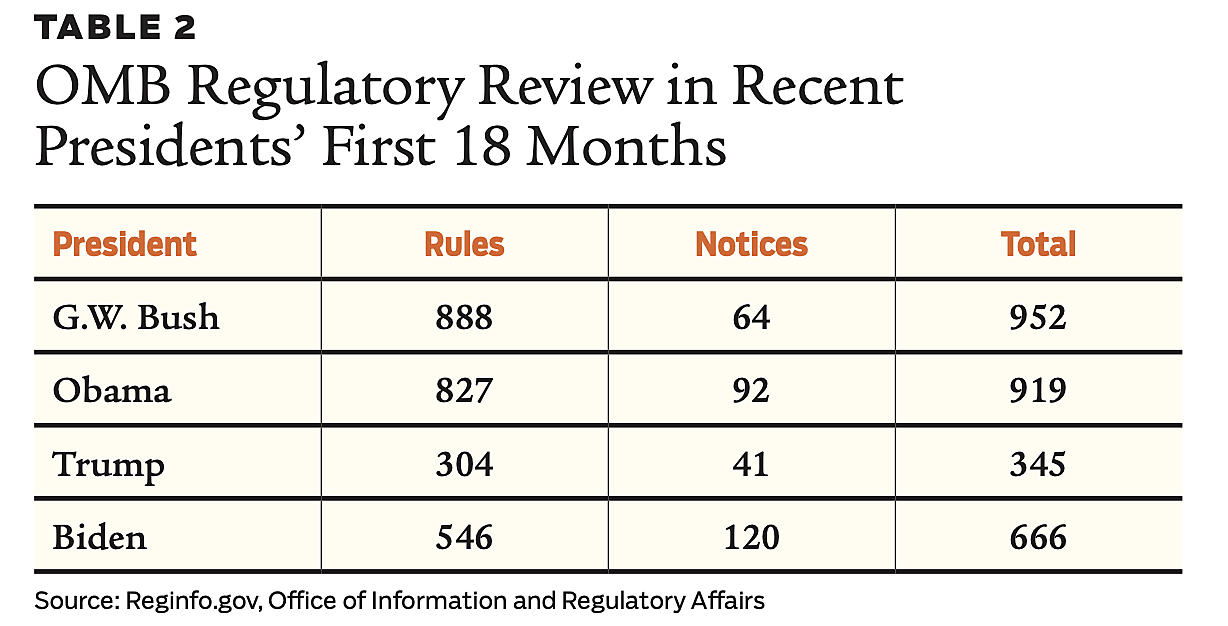

The numbers / With respect to quantity, Table 2 presents the results across the four most recent presidential administrations.

The table provides three insights: First, OMB output was lowest under Trump, who deliberately made it harder for agencies to issue new regulations and therefore send them to OMB for review. Second, OMB output under Bush and Obama was high and comparable in magnitude, reflecting a large number of significant regulations in the queue. It may seem odd that OMB was so busy in the Bush administration, but one must account for the uptick in regulatory activity in the aftermath of 9/11. The similarity to Obama would not continue once the slug of homeland security regulations worked its way through the system. Third and most surprising, OMB output under Biden has been only two-thirds that under Obama.

The data in Tables 1 and 2 lead to the following conclusion: compared to Obama, Biden is issuing more impactful regulations with less OMB oversight.

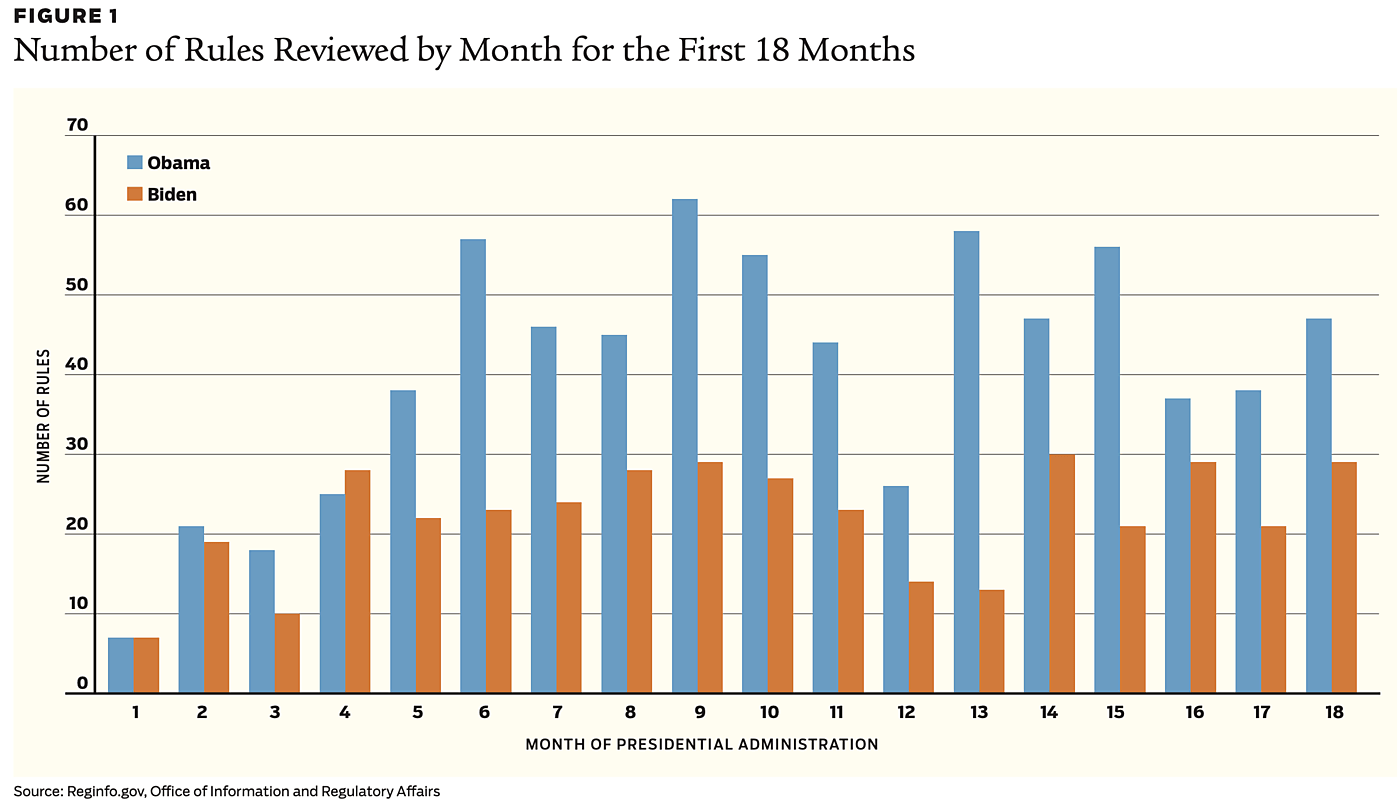

Is the decline in OMB output consistent across the first 18 months of the Biden administration, or does it reflect an uneven rate of OMB review? To answer this question, I plotted the number of OMB concluded reviews by month for both Obama and Biden. Excluded are economically significant rules. Figure 1 shows that the noted decline is consistent across time. In only one month did the Biden OMB conclude review of more rules than the Obama OMB. Furthermore, the average time of review was similar, with Biden taking just a handful of days longer, on average, than Obama.

Perhaps OMB resources for regulatory review have declined? After all, the fall in regulatory activity under Trump could have led to a decrease in staffing that carried over into the Biden administration. However, OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), which conducts regulatory review, has not seen a noticeable decline in staffing since well before the George W. Bush administration. And, as previously noted, the average time for OMB review has changed little under Obama versus Biden. It does not appear that resources explain the decline in OMB output. (A decline in resources should not affect the number of rules that OMB designates as significant; however, it could cause OMB review to take longer or decline in rigor.)

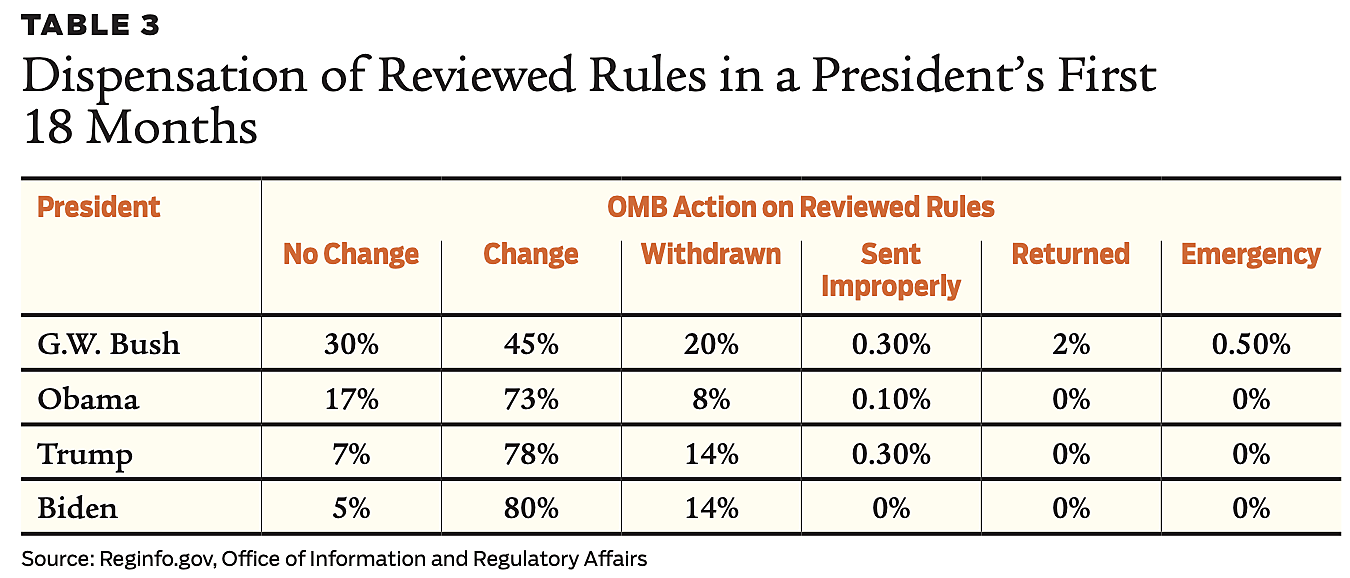

Quality of review / We see that the quantity of reviewed rules has declined, but what about the quality of review? When OMB concludes review of a rule, it notes whether the draft rule has been changed or not. Change indicates OMB concerns have been addressed. Although aggregate statistics do not reveal the extent to which OMB changed a rule, one can infer from the rate of withdrawals/returns whether OMB is being aggressive (making major changes) or passive (making minor changes) in its review. The more often an agency either withdraws a rule or OMB returns it, the more aggressive OMB review. Table 3 presents the data on OMB dispensation of reviewed rules.

The table shows that OMB review under Biden is actually more aggressive (more rules are changed and more rules are withdrawn) than under Bush or Obama, and about the same as under Trump. It seems that when the Biden OMB does review rules, it does so with a relatively discerning eye.

This is good news: OMB is scrutinizing Biden rules as rigorously as it has under previous presidents. But why is it concluding review on fewer significant rules, as Table 2 shows?

Three possible explanations come to mind:

- 1) OMB is designating fewer agency rules as significant for review (and proposed rules that were designated significant before Biden came to office are still being finalized).

- 2) OMB designations have not changed, but agencies are submitting fewer designated rules to OMB for review.

- 3) OMB designations and agency submissions have not changed, but OMB is taking much longer to conclude review.

The data rule out the third explanation. OMB reviews are not taking longer over time. Under Biden, review times have changed little month to month. This leaves fewer OMB designations or fewer agency submissions as the possible explanation. It seems unlikely to be the latter. Regulatory agencies are typically eager to issue new regulations, especially in an administration that is positively inclined to regulate. Furthermore, Biden is finalizing the most important rules (major rules and significant rules) at roughly the same rate as Obama (see Table 1). We would not expect to see this if agencies were failing to submit rules for OMB review in a timely manner. By process of elimination, the explanation must be that OMB is designating fewer rules as significant. That appears to be happening even though Biden has not formally changed the long-standing criteria under which OMB makes a significance determination, which is embodied in executive Order 12866, issued by Bill Clinton. If OMB is designating fewer rules as significant, then at some point the number of significant rules published in the Federal Register under Biden should become even lower than under Obama.

For those who expect Biden’s regulatory activity to mirror Obama’s, let me suggest one reason why this might not be so. After 18 months in office and counting, Biden has yet to nominate someone to serve as OIRA administrator. All other recent presidents have, after taking office, quickly nominated someone who was confirmed by the Senate. This is not an insignificant difference. A Senate-confirmed OIRA administrator provides a counterweight to agency heads (who are also Senate-confirmed) when disagreements arise on regulatory matters. It is not unreasonable to assume that OMB with a Senate-confirmed OIRA administrator will be less likely to capitulate on a significance designation if an agency pushes back. It is also not unreasonable to assume OMB will be less likely to capitulate on changes it recommends to draft regulations.

It seems odd to reaffirm OMB’s traditional role in regulatory review—as Biden did early in his term—and never nominate someone to serve as OIRA administrator. Yet here we are.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.