The past decade has witnessed an impressive turnaround in academic thought on executive pay. Prior to the financial panic of 2008, the leading school of thought — championed perhaps most notably by Harvard professors Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried in their book Pay Without Performance — was that corporate executives had too comfortable a life: they were paid too much, and without regard to the performance of their firms. This led to calls for reform such as the Dodd-Frank “Say on Pay” — giving shareholders the ability to voice an opinion on executive pay packages — and other forms of shareholder empowerment, in the hopes that shareholders would tie executive pay more closely to the performance of the firm.

However, in the economic fallout of the financial panic, the leading school of thought on executive compensation has shifted from prescribing greater performance-based compensation to prescribing compensation systems designed to limit risk-taking and managerial short-termism. In fact, according to these proposals, shareholders cannot be trusted to set executive compensation since shareholders themselves do not bear the full downside when the firm's debt is impaired, employees are laid off, or the government bails out a systemically important firm (as happened with AIG, for example). With regard to the substantive components of pay, while not abandoning completely the pre-2008 mantra of pay for performance, these compensation reforms would focus (sometimes exclusively) on long-term results in determining an executive's variable pay. For instance, Bebchuk and Fried now propose that any equity awards managers receive must be restricted so that they cannot be cashed out for a period of years. Going further, Yale professor Roberta Romano would disallow cashing out until some time after the executive's retirement. Such schemes, along with a mechanism for forfeiting pay in the event of malfeasance or poor performance, form the backbone of these new proposals. The sponsors of such plans view them as advisable for most or even all firms — a new set of best practices.

However, in the case of "systemically important" institutions such as large banks and securities firms, these measures are advocated not just as optional best practices but rather as mandatory elements of executives' compensation contracts. The rationale for such a fiat is that the government must backstop institutions that are "too big to fail" or otherwise too systemically sensitive, and as such the government is a major stakeholder — a guarantor and potential residual claimant in the event of failure.

How broadly will these measures apply? If it were merely depositary institutions in the regulatory gunsights, that would be one thing. But given recent moves to regulate hitherto largely unregulated swaths of financial markets — such as hedge funds and private equity — on the grounds that they too are systemically important, forthcoming regulation could be far-reaching indeed.

At the current time, such practices have begun to be implemented and more may be on the way. Dodd-Frank has given regulators authority over executive pay and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation recently used that authority to propose two-year clawbacks for executive pay at failed banks. (However, as of the time of this writing, according to The Economist, an insurance market protecting managers against such clawbacks has already developed.) Some investment banks, such as Morgan Stanley, have begun to institute similar measures voluntarily, perhaps in an attempt to forestall further regulation.

This all, then, begs the questions: Are these long-term compensation schemes a good idea? Will they do what their advocates promise? And are there good reasons why firms and shareholders have not adopted such schemes on their own? In this article, I address these questions. In short, while long-term compensation has potential benefits — it can deter bad behavior that will only be observed later and can limit risk taking — such benefit will be limited in scope under all but the most extreme of the plans. More worrisome, the focus on long-term pay can have great costs: managers may seek to limit their own risk in ways that harm the firm and the economy, while constraining compensation to ignore short-term results means that useful information about managerial performance is being ignored.

What Is Being Proposed? And Why?

Generally speaking, there are three main features of the long-term reforms. These are "restriction" or deferral of equity grants, mandatory clawbacks of bonus pay, and divestment of deferred compensation upon the discovery of malfeasance. Below is a brief description of each of these.

Restricted equity grants | While many firms award equity or equity options to executives, such grants are often unrestricted in the sense that they may be sold or exercised immediately or in a short period of time. Bebchuk and Fried (2009) would require firms to restrict equity grants for a period of years, while going further, Sanjai Bhagat and Romano (2009) would restrict equity grants until retirement. The intuition for such restrictions is straightforward: if managers are too concerned with short-term price movements, then making their compensation longer-term will lead managers to take a longer-term view.

Clawbacks | In current practice, bonus structures are often asymmetric in that, in good times, executives take home hefty pay packages, while in bad times they have a small or zero bonus. Bebchuk and Fried (2009) and Bebchuk and Holger Spamann (2010) would require that bonus compensation be granted symmetrically: what executives gain for apparent success they should lose when those successes are subsequently reversed. Bonuses would be held in trust so that subsequent bad performance may be netted out of any payment given to the manager. Such a scheme is meant to eliminate the incentive to temporarily boost performance in one year at the expense of performance in other years, such as by undertaking a project that the manager knows to be net-negative expected value but that may be favorably perceived by the marketplace in the short term or, even more directly, by accounting fraud.

Divesting of grants upon discovery of fraud/excessive risk | While the deferral of equity and bonus compensation acts as a carrot for long-term performance, divesting of deferred compensation provides a stick to discourage bad behavior. If opportunistic managerial behavior is discovered later on by shareholders, regulators, or courts, then the restricted stock or held-in-trust bonuses above will be divested from the executive. Assuming misbehavior is ex post verifiable, it will, ex ante, deter managers from engaging in misbehavior in the first place.

What Are the Costs of these Proposals?

There are certainly potential benefits to be had from a focus on long-term compensation. Executives who are invested for the long term will tend to focus on stock price in the long term. Executives who are subject to downside for poor performance (or performance reversals following good performance) refrain from manipulation of short-term prices that come at the expense of long-term value. The potential revocation of restricted stock grants and bonus compensation can be a good deterrent where managerial malfeasance is likely to be discovered only after the significant passage of time.

However, as I will discuss in this section, there are some problems with these approaches. First, it is not clear how much different, in functional terms, these proposals would be from the status quo. With restricted equity plans, unless the period of restriction is significant relative to the manager's expected tenure, incentives in restricted and non-restricted plans are largely identical. Only in the most extreme restricted stock plans, such as Bhagat and Romano's hold-until-retirement scheme, are executive incentives almost everywhere different. As for the clawback proposal, the likely effect is simply to shift compensation from bonuses into salaries; if wages are already subject to market discipline, then larger salaries will have to offset the negative bonuses that accrue for poor performance.

Second, to the extent that these plans do represent substantive changes, it is not clear that they are for the good. Executive risk aversion makes deferred and contingent compensation generally more expensive. While deferred compensation may reduce or eliminate some forms of opportunism, executives will still have incentives to act opportunistically in other ways: executives may delay projects or disclosures to coincide more closely with the cashing out of restricted stock, or they may undertake inefficient measures to reduce the firm's overall risk. Additionally, artificially restricting compensation factors to long-term results loses potentially valuable information contained in short-term results.

Long-term restricted equity | While long term compensation may be effective in some circumstances to remedy some aspects of managerial opportunism, there is a fairly obvious tradeoff: by removing compensation from the here and now, incentives to do appropriate things in the immediate term are lessened. I explore those problems in this section.

How great is the difference between restricted and non-restricted stock plans? As a preliminary matter, under the Bebchuk and Fried (2009) proposal, there is a potentially large period of time when the incentives of the manager will not in fact be any different than in the non-deferred case. If deferral is for x years, then x years after the manager began employment the manager will be cashing out some constant amount of stock each year, just as in a non-deferred plan. Thus, over a relatively long tenure period, there is little added focus on long-term results.

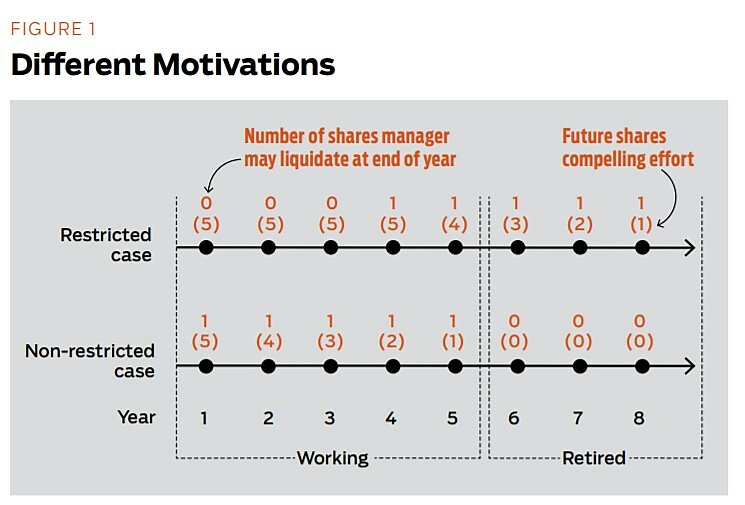

Suppose for example that the manager of a firm has a tenure of five years, after which she retires. In addition to paying a wage w, a firm may either grant a share of stock to the manager at the end of each year (non-restricted equity) or else grant three-year restricted stock. That is, the non-restricted manager simply takes home a share of stock at the end of each year, while the restricted manager takes home nothing for the first three years, then a share of stock at the end of year 4 and thereafter, until three years after her retirement. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of liquid equity compensation to the manager in each year under each plan.

The restricted manager may sell one share of stock in years 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. The non-restricted manager may sell one share of stock in years 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. The number in parentheses in Figure 1 gives the amount of stock that has yet to vest in the manager at the time the manager is deciding whether to exert effort; this not-yet-vested stock is what compels effort from the manager.

As it turns out, there is a stretch of time in the deferred and non-deferred cases in which the manager's incentives are the same. Under the non-restricted compensation scheme, in year 1 the manager looks forward to five shares of equity compensation. Whatever benefit the manager is able to bestow upon the firm — suppose he may generate an asset with value A per share, which increases stock price by A — will be partially appropriated by him via his five shares of stock. Thus he would exert effort if the cost of effort (C) is less than 5 × A. In the restricted equity case, the manager in period 4 looks forward to five years of equity compensation. Again, the value of each share will be increased by A should the manager exert effort, and as in the non-deferred case, the manager will choose to exert effort if 5 × A > C. Thus, incentives in year 1 of the non-restricted case are the same as incentives in year 4 of the restricted case. Similarly, year 2 in the non-restricted case is also equivalent to year 5 in the restricted case.

There are, however, periods of time in which incentives differ; the restricted scheme incentives are sometimes, but not always, an improvement and may in fact be a detriment. Consider again the Figure 1 example. Take the manager in the last year of employment — year 5 — under a non-restricted scheme. He will receive only one share of stock in the future, and thus will choose to exert effort in year 5 only if C < A. There is no comparable incentive in the deferred case. What this means is that managers in restricted stock schemes will tend to have better incentives as they near retirement than do managers in unrestricted schemes. In comparison to the unrestricted scheme, the executive in year 5 under the restricted stock plan still has four shares of stock that have yet to vest, meaning that he will exert effort so long as C < 4 × A. Thus, in the last years of employment, restricted plans tend to compel more effort.

On the flip side, though, at the beginning of the manager’s employment, he receives no saleable stock for the first three years under the restricted stock plan, which gives potentially (though not necessarily, as in the risk-neutral case) different incentives than in the non-restricted case. If there exists uncertainty about the value of the asset and risk aversion on the part of the manager, restricted grants in the beginning periods have negative incentive effects — risk-averse managers are unwilling to undertake costly effort given uncertain outcomes — that oppose the salutary effects of deferred compensation at the end of the manager’s tenure. At the same time, those salutary effects of deferring compensation into retirement are lessened: a risk-averse manager may be unwilling to exert effort in the current period in order to receive an uncertain benefit sometime in the future. So, for example, where risk aversion is so extreme that equity grants outside the current period are completely discounted in deciding whether to undertake effort, the non-restricted scheme dominated the restricted scheme. More generally, the greater the degree of risk aversion and uncertainty, the shorter any restriction period should be. I explore problems of uncertainty and risk aversion in more detail in the next section.

Risk aversion and undesirable risk-reduction If the manager is not risk-averse (and, for simplicity, assuming zero discounting), the manager is indifferent between receiving his equity share now or at any point in the future. For example, promising to pay the manager a share of equity in 10 years would present no problems. In such a state of the world, the Bhagat and Romano (2009) scheme of deferral until after retirement is preferable.

However, once the manager is risk averse and there is uncertainty, he finds waiting to be costly. Suppose his effort creates an asset with an expected value of A. When that asset is observed by the marketplace, the stock will increase by amount A. Over time, however, the value of that asset, along with the rest of the firm’s value, will fluctuate randomly in an efficient market. (Typically, economists view securities prices as a random walk.) The longer the manager must wait before exercise, the more the value of the asset will vary and the more risk he bears. This means that the increase of A in stock price becomes less of an inducement to exert effort in the near term because the increase in stock price is subject to the same random fluctuations — i.e., risk — as is the rest of the stock’s value.

This means that a manager receiving a share of equity in the current year would require less in terms of equity compensation in order to be willing to exert effort than in the case where compensation is deferred. The magnitude of this problem depends upon the manager’s level of risk aversion. One partial solution may be paying the manager more: if risky stock is less valuable to the manager, then paying more stock may make up the incentive problem. This is, however, more expensive for shareholders and leads to higher overall levels of executive compensation. Further, it is not a complete solution to all forms of risk aversion.

Executives, when faced with a riskier compensation profile, may seek to limit the firm’s risk in ways that are inefficient.

In such a situation, managerial behavior becomes distorted. One problem that arises immediately is that executives, when faced with a riskier compensation profile, may seek to limit the firm’s risk in ways that are inefficient. While limiting risk is inarguably part of the purpose of these proposed reforms, managers may choose either to minimize risks that are not a problem or to undertake risk-reduction measures that are socially undesirable. For instance, if the goal is to limit systemic risk, such a goal may fail if the manager chooses instead to reduce the firm’s idiosyncratic risk by firm-level diversification while still maintaining the same systemic bets.

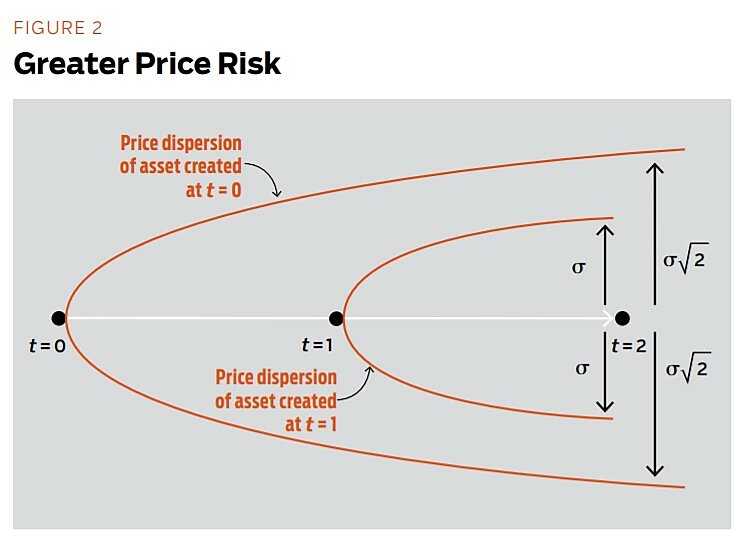

A more subtle problem arises from the fact that managers may change their timing of effort in order to minimize their risk and maximize their expected utility from their future stock awards. Suppose a manager of a pharmaceutical firm has two-year restricted stock and has a new potential drug with an expected value of $10 per share. Should the manager begin the testing, approval, and marketing process now or wait until later? Upon announcement, the firm’s stock will rise by the expected value — $10 per share — which will then fluctuate as the product introduction process goes either well or badly. Clearly, the risk-neutral shareholders would prefer that she undertake the process now, since idiosyncratic risk does not affect her, and waiting carries some possibility that the firm’s product will be preempted by the competition. The manager, on the other hand, has nothing to gain in the near term from an announcement and, in fact, he will find it costly to bear the risk of the approval process and consequent price fluctuations. Instead, he may find it preferable to announce the project and begin the approval process just before his stock options vest, such that he enjoys the $10-per-share rise with certainty — even if there is some risk of being preempted in the meantime. Figure 2 illustrates this choice: if the manager undertakes the project and creates the asset at t = 0, he bears greater price risk than if he waits until t = 1 to undertake the project.

Limiting disclosure | If managers are paid exclusively in long-term compensation, they have little, if any, incentive to make disclosures about the firm’s health in the short term. This has negative effects upon the liquidity of the firm’s shares and ultimately would increase a firm’s ex ante cost of capital.

Consider a manager who learns a piece of positive but uncertain information in year 1: the firm has acquired a project, for concreteness, that is distributed normally with expected value v and variance σ > 0 . She has the choice of disclosing it then or waiting until year 2, at which time she is able to sell her restricted share of stock. Further, suppose that the manager will know more about the value of the project in year 2: the project’s variance declines by some positive amount d. What would she choose to do?

In a perfect world, absent concerns of secrecy or competition, the manager would disclose immediately. This has the salutary effects of lowering the firm’s cost of capital (should it be seeking to raise capital) in year 1 and of lowering liquidity costs for the firm’s shareholders by reducing uncertainty and incentives to engage in costly informational search.

However, the manager has little reason to disclose in year 1. She has no upside in doing so, since her stock sale cannot occur until year 2. She would, on those facts, be indifferent between immediate and delayed disclosure. Further, she faces costs from immediate disclosure. The securities laws impose personal liability on managers who make false disclosures, and forward-looking statements — expectations regarding future value — are considered particularly risky in this regard. If findings of liability are prone to error (a generally accepted assumption), then this creates a very real risk of liability for the manager of telling the truth in year 1. She is better off waiting until year 2, when she has better information — lowering her personal liability — and some economic interest compelling her to make the disclosure.

Loss of information There is a potential loss of efficiency in ignoring or suppressing short-term results. The reason is that there may be cases in which short-term results reflect additional information about the efforts and behavior of managers that is not picked up by the long-term stock price.

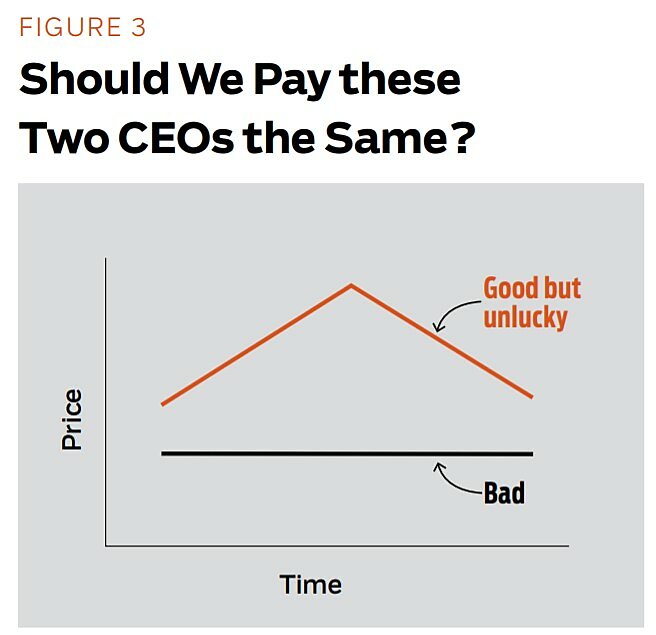

Imagine the following scenario: In year 1, the manager undertakes effort to create an asset that has an uncertain but positive expected value; in year 2 the asset may generate cash flows of $10 with probability p and cash flows of $0 with probability 1– p. At the end of year 2, the firm pays a dividend and winds up. The likelihood of generating an asset in year 1 depends upon whether the manager is good or bad: for simplicity, suppose that good managers always generate the asset, while bad managers never do.

Figure 3 illustrates the identical returns of an unlucky good manager and a bad manager: the top line is the price trajectory of a manager who is good and generates an asset that ultimately (and unluckily) does not pan out, while the bottom line is the bad manager who cannot generate an asset at all. Each has a total return of zero.

How should shareholders compensate the manager, and based on what metric? It is apparent that the year‑1 stock price is perfectly revealing of the manager’s type: good managers always generate year‑1 stock price of pA while bad managers always generate stock price of 0. Hence, it would be quite reasonable to base pay at least partially on short-term results. In contrast, the year‑2 stock price is not perfectly revealing: both good and bad managers can result in two-year returns of zero.

To an extent, stock compensation based on year‑2 price could still induce good managers to work hard: a risk-neutral manager can simply be awarded k shares of restricted stock (i.e., stock that is exercisable only at the conclusion of year 2) such that kpA equals her market wage. However, a risk-averse manager (the more likely case) will require an additional amount of compensation ε to compensate her for the risk that she bears. That is, the fact that managers are risk-averse in general makes it costly to shareholders to compensate the manager for risk that the shareholders themselves (presumably diversified and risk-neutral) could more efficiently bear. Here, specifically, paying the risk-averse manager in two-year restricted stock costs the firm’s shareholders an additional amount ε, which would not be required if the manager received year‑1 stock instead.

An additional complication is whether the manager is to be renewed at the end of her term. Clearly in the example above, shareholders would be wise to retain a manager (or induce her to remain) who generates the year‑1 stock price of pA, even if the price subsequently declined to 0 in year 2. Such a manager is, without doubt, of good type. However, it is not clear that under a mandatory long-term compensation rule this would be allowable.

This is not to say that there is no case to be made for weighting more heavily upon long-term performance. In the above example, suppose that bad managers can mimic good managers: they can artificially raise year‑1 stock price, only to always have that price increase reversed in year 2. In such a case, period‑1 stock price is perfectly unrevealing and the only information shareholders will have regarding managerial type is in the noisy revelation that takes place in period 2. A less extreme example would be where bad managers may be sometimes unsuccessful in mimicking; in such a case, both year‑1 and year‑2 stock prices contain useful information that should be incorporated into the manager’s compensation contract. What one can say, though, is that as a general matter, mandating zero weight upon short-term results is a bad idea.

A somewhat different problem arises where a firm may do poorly in the first year, a species of the well known “gambling for resurrection” problem. If a manager is subject to some sort of return averaging over her tenure, this may give her bad incentives to increase risk. For instance, suppose the manager receives an option priced at the money as of the start of her employment that is exercisable only at the end of year 2; this rewards the manager based on the total return of the firm during that time, from year 0 to the end of year 2. If the price declines in year 1 — whether or not it is the manager’s fault — her option is underwater and she now has the incentive to “gamble for resurrection.” She may seek to increase the firm’s risk, even at the expense of some expected value. Again, shareholders would be better off taking year‑1 stock price into account rather than tying the manager’s compensation plan exclusively to year 2. In this particular case, the change from year 0 to 1 may reveal something negative about the manager’s effort or competence that may be masked by the assumption of additional risk in year 2, and the (again, short-term) change from year 1 to 2 may reveal something else about the level of risk that the manager has taken on.

Clawbacks | One aspect of several of the current proposals (e.g., Bebchuk 2010) is the mandatory clawback feature with regard to bonuses. This is meant to be, and probably is, a useful deterrent to fraudulent activity. For instance, if an executive overstates revenues in one period, the clawback feature would require her to give up any performance bonus if that fraud is ultimately discovered. Further, clawbacks may be based not just on fraud, but rather upon a “reversal” of the firm’s fortunes or where the reasons for paying the bonus in the first place no longer hold up. This poses at least two distinct problems. The first springs from the discretionary nature of what a firm’s compensation committee might count as a success for which a bonus should be granted, and a failure for which a bonus should be taken back. This is a problem that does not exist when one assumes, as in the restricted stock case, that the variable compensation is going to be paid as equity. Second, without fairly extreme assumptions of market inefficiency, a clawback system ends up looking not much different than a non-clawback system.

Defining success and failure for clawbacks In a typical optimal compensation problem, shareholders cannot directly observe or contract for the manager’s effort. Rather, the manager’s effort can be inferred ex post through the firm’s subsequent returns, although not necessarily with certainty. A standard solution, then, is to award the manager “bonus” compensation that is contingent upon a good outcome. In order to induce the manager to exert effort and otherwise behave well, the manager’s expected gain from doing so must exceed the costs of exerting effort and refraining from misbehavior. What that means is that, so long as the spread between the manager’s reward for success and punishment for failure is sufficiently great, it does not matter what absolute level the bonus and punishment are set at, or what salary the manager receives in addition. The additional consideration of limited liability tends to militate for a solution in which the manager’s overall compensation cannot be negative, while a manager’s risk aversion makes it overall less expensive for shareholders to pay a significant portion of the manager’s compensation in salary.

The discretionary nature of what a firm’s compensation committee might count as a success or failure, and the efficiency of the manager compensation market, create two distinct problems for “clawback” proposals.

The mandatory clawback proposal would require, essentially, that a negative bonus or penalty be assessed against a manager such that the loss from a subsequent failure will cancel out the gains from a previous success. Clawbacks or their equivalents exist voluntarily in many settings, such as hedge funds and private equity (whose customary 20 percent incentive compensation, or “carry,” is subject to “highwater marks” for leading losses and clawbacks for subsequent losses) as well in the mortgage origination business (where mortgage purchasers retain the right to put back the mortgage to the originator in the case of early default or the discovery of fraud). In such cases, the parties have decided to impose clawbacks based on certain well-defined events (portfolio value declines and fraud/default, respectively), and this is perhaps why it makes sense in these cases.

As a general one-size-fits-all approach, however, things are not so clear. What defines success in an executive’s role? If we condition bonuses specifically upon a rise in stock price, this ignores the case where a company may do well simply to avoid losing any more money; for example, given a bleak outlook, a 1 percent decline may well be what defines success. If success and failure are hard to define such that regulators or legislators cannot do it, there is little to keep a compensation committee that chafes at pay mandates from defining success and failure in such a way that bonuses become again non-contingent, taking the teeth out of the mandatory clawback system.

The equivalence of clawback and non-clawback systems At the end of the day, a system of mandatory clawbacks — negative bonuses in the event of performance “reversal” — is likely to resemble a system of large bonuses for success and zero bonuses otherwise — i.e., a non-clawback bonus system. The reason is that under such a system, salary components of compensation will have to rise to make up for the potential of a negative bonus. If, in order to guarantee solvency to repay the negative bonus, the firm must hold part of an executive’s salary in trust until bonus-time, the end effect is exactly the same. It is thus possible that a mandatory clawback requirement will have no effect at all.

For example, consider an executive who receives both a salary and a performance-based bonus in two years. Suppose that the executive has two choices in the first year: costly effort or no effort plus fake performance, which is subsequently reversed in the second year. In the second year, the executive simply rides things out. Suppose further that the market wage for an effort-exerting executive is $10 per year, and that the executive’s cost of effort is $3.99. As it turns out, we can formulate any number of efficient compensation schemes.

Consider first a non-clawback system. The firm could pay the executive a base salary of $6 and a bonus of $4 in each year, the latter contingent upon good results. If the executive behaves himself — meaning he exerts effort — he would receive $10 in each years 1 and 2. In contrast, a cheating executive would receive $10 in year 1 and $6 in year 2. At the start of year 1, then, knowing this, what would the executive choose to do? He would exert effort in order to receive $10 in each year, since his net payoff ($20 less the $3.99 cost of effort) is a penny greater than his net payoff from cheating ($16). No clawback structure is needed to deter cheating; rather, the likelihood of foregoing a sufficiently large bonus in the future is all that is required.

Alternatively, the firm could impose a clawback structure: the executive receives a salary of $8 in each year, along with a $2 bonus for good performance and a –$2 penalty for a reversal of good performance. As before, a cheating executive would receive $10 in year 1 and $6 in year 2, while the non-cheating executive receives a total of $20. Again, good behavior is ex ante preferable.

What this example shows is that there is not necessarily any difference between properly constructed clawback and non-clawback compensation systems. Executives who will stay with the firm are dependent upon the payment of future salary and bonuses; reversible cheating will hence come out of his future compensation. Further, one can show that clawbacks are no panacea: suppose the executive receives $9 salary with a $1 bonus subject to clawback. In such a case, the executive will choose to cheat: he would make $10 in year 1 and $8 in year 2, and since by construction a differential of $4 is required to ensure good behavior, cheating is an equilibrium outcome. Hence, a clawback system is not necessarily efficient, as it still requires the firm to properly assess the incentives to cheat in structuring bonuses and is unlikely to be better than a properly constructed non-clawback system.

Are there conditions under which the clawback system is preferable? Potentially, yes: if executives who cheat plan on leaving the firm, then a clawback held in trust can deter such cheating. Suppose that an executive, after claiming his bonus in year 1, leaves the firm for another. In the non-clawback case, the manager receives his $10 plus whatever his second firm will pay him. In the clawback case, the executive’s bonus pay is held in trust and may be divested upon the discovery of cheating.

What this means, then, is that in cases where executives depart their current firms, additional safeguards (i.e., some deferral of compensation) are wise. As is well-recognized (e.g., Todd Henderson and Spindler 2005), executives who may leave their current firms face final-period problems where trust is difficult to guarantee. In such specific cases, some form of protection is advisable, and if taxpayers may be the ones on the hook for firm failure, then such regulation may be desirable. Outside of such a limited context, however, it is unlikely that mandating such constraints will do much that is useful.

Conclusion

There are undoubtedly benefits to various forms of long-term compensation: deferred compensation can limit excessive risk-taking and the possibility of divesting can deter opportunistic actions that may not be discovered until later. However, this article shows that some of the mandated reforms may not be all that much different than present-day practices and that, to the extent that these reforms do create substantive differences, they are not necessarily preferable.

Readings

- “Corporate Heroin: A Defense of Perks, Executive Loans, and Conspicuous Consumption,” by M. Todd Henderson and James C. Spindler. Georgetown Law Journal, Vol. 93 (2005).

- “How to Fix Bankers’ Pay,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk. Daedalus, Vol. 139 (2010).

- “How to Pay a Banker,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk. Project Syndicate, 2010.

- “Paying for Long Term Performance,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Jesse Fried. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 158 (2010).

- “Reforming Executive Compensation: Focusing and Committing to the Long-Term,” by Sanjai Bhagat and Roberta Romano. Yale Journal on Regulation, Vol. 26 (2009).

- “Regulating Bankers’ Pay,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Holger Spamann. Georgetown Law Journal, Vol. 98, No. 2 (2010).

- “Taming the Stock Option Game,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Jesse Fried. Project Syndicate, 2009.

- “Why Bankers’ Pay Is the Government’s Business,” by Lucian A. Bebchuk. Economist.com, 2010.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.