EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

State governments have been in an expansionary phase in recent years. Even though U.S. economic growth since the last recession has been sluggish, general fund revenues of state governments have grown 33 percent since 2010. Some of the nation’s governors have used the growing revenues to expand spending programs, while others have pursued tax cuts and tax reforms.

That is the backdrop to this year’s 13th biennial fiscal report card on the governors, which examines state budget actions since 2014. It uses statistical data to grade the governors on their taxing and spending records—governors who have cut taxes and spending the most receive the highest grades, while those who have increased taxes and spending the most receive the lowest grades.

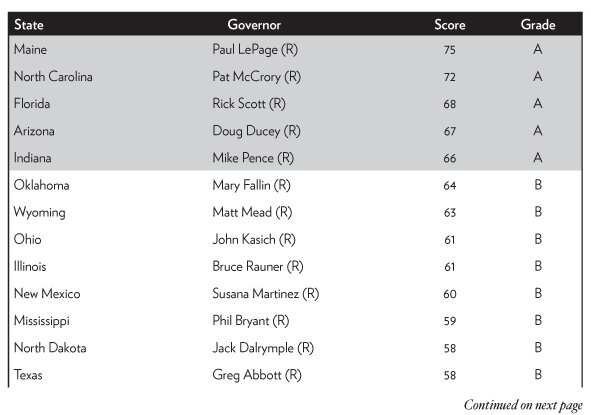

Five governors were awarded an “A” on this report: Paul LePage of Maine, Pat McCrory of North Carolina, Rick Scott of Florida, Doug Ducey of Arizona, and Mike Pence of Indiana. Ten governors were awarded an “F”: Robert Bentley of Alabama, Peter Shumlin of Vermont, Jerry Brown of California, David Ige of Hawaii, Dan Malloy of Connecticut, Dennis Daugaard of South Dakota, Brian Sandoval of Nevada, Kate Brown of Oregon, Jay Inslee of Washington, and Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania.

With the growing revenues of recent years, most states have balanced their short-term budgets without major problems, but many states face large challenges ahead. Medicaid costs are rising, and federal aid for this huge health program will likely be reduced in coming years. At the same time, many states have high levels of unfunded liabilities in their pension and retiree health plans. Those factors will create pressure for states to raise taxes. Yet global economic competition demands that states improve their investment climates by cutting tax rates, particularly on businesses, entrepreneurs, and skilled workers.

This report discusses fiscal policy trends and examines the tax and spending actions of each governor in detail. The hope is that the report encourages more state policymakers to follow the fiscal approaches of the top-scoring governors.

Introduction

Governors play a key role in state fiscal policy. They propose budgets, recommend tax changes, and sign or veto tax and spending bills. When the economy is growing, governors can use rising revenues to expand programs or they can return extra revenues to citizens through tax cuts. When the economy is stagnant, governors can raise taxes to close budget gaps or they can trim spending.

This report grades governors on their fiscal policies from a limited-government perspective. Governors receiving an A are those who have cut taxes and spending the most, while governors receiving an F raised taxes and spending the most. The grading mechanism is based on seven variables, including two spending variables, one revenue variable, and four tax-rate variables. The same methodology was used on Cato's 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014 fiscal report cards.

The results are data-driven. They account for tax and spending actions that affect short-term budgets in the states. But they do not account for longer-term or structural changes that governors may make, such as reforms to state pension plans. Thus the results provide one measure of how fiscally conservative each governor is, but they do not reflect all the fiscal actions that governors make.

Tax and spending data for the report come from the National Association of State Budget Officers, the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Tax Foundation, the budget agencies of the states, and news articles in State Tax Notes and other sources. The data cover the period January 2014 through August 2016, which was a time of budget expansion in most states.1 The report covers 47 governors. It excludes the governors of Kentucky and Louisiana because of their short time in office, and it excludes Alaska's governor because of peculiarities in that state's budget.

The following section discusses the highest-scoring governors, and it reviews some recent policy trends. The section after that looks at the outlook for state budgets, with a focus on the longer-term burdens of debt and underfunded retirement plans. Appendix A discusses the report card methodology. Appendix B provides summaries of the fiscal records of the 47 governors included in this report.

Main Results

Table 1 presents the overall grades for the governors. Scores ranging from 0 to 100 were calculated for each governor based on seven tax and spending variables. Scores closer to 100 indicate governors who favored smaller-government policies. The numerical scores were converted to the letter grades A to F.

Table 1. Overall Grades for the Governors

Highest-Scoring Governors

The highest-scoring governors are those who supported the most spending restraint and tax cuts. Here are the five governors who received grades of A:

-

Paul LePage of Maine has been a staunch fiscal conservative. He has held down spending growth, and state government employment has fallen 9 percent since he took office. LePage has been a persistent tax cutter. In 2011 he approved large income tax cuts, which reduced the top individual rate and simplified tax brackets. In 2015 he vetoed a tax-cut plan passed by the legislature partly because the cut was not large enough. The legislature overrode him, and Maine enjoyed another income tax reduction. In 2016 LePage pushed for more reforms, including estate tax repeal and further income tax rate cuts.

-

Pat McCrory of North Carolina came into office promising major tax reforms, and he has delivered. In 2013 he signed legislation to replace individual income tax rates of 6.0, 7.0, and 7.75 percent with a single rate of 5.8 percent. That rate was later reduced to 5.75 percent. The law also increased standard deductions, repealed the estate tax, and cut the corporate tax rate from 6.9 to 4.0 percent, with a scheduled fall to 3.0 percent next year. In 2015 McCrory approved a further individual income tax cut from 5.75 to 5.5 percent. McCrory has matched his tax cuts with spending restraint. The general fund budget will be just 8 percent higher in 2017 than it was when the governor took office in 2013.

-

Rick Scott of Florida says that he wants to make Florida the best state for business in the nation, and tax cuts are a key part of his strategy. In 2012 Scott raised the exemption level for the corporate income tax, which eliminated the burden for thousands of small businesses. In 2014 he signed into law a $400 million cut to vehicle fees. In 2015 Scott approved a cut to the state's tax on communication services and reductions in sales taxes and business taxes. In 2016 he approved the elimination of sales taxes on manufacturing equipment, which is an important pro-investment reform. Scott also scored well on spending, and he has trimmed state government employment by 4 percent.

-

Doug Ducey of Arizona was the head of Cold Stone Creamery, and he has brought his business approach to the governor's office. He has overseen lean budgets, with general fund spending on track to rise just 2 percent between 2015 and 2017. He approved major pension reforms, including trimming benefit costs and giving new state employees the option of a defined contribution plan. Ducey has approved substantial tax cuts, including ending sales taxes on some business purchases, reducing insurance premium taxes, increasing depreciation deductions, and indexing Arizona's income tax brackets for inflation.

-

Mike Pence of Indiana has been a champion tax cutter and fairly frugal on spending. In 2013 he signed into law a cut to Indiana's flat individual income tax rate from 3.4 percent to 3.23 percent. He also approved a repeal of Indiana's inheritance tax. In 2014 he cut the corporate income tax rate, which has fallen from 7.5 percent to 6.25 percent since 2014, and is scheduled to fall to 4.9 percent in coming years. Pence also reduced property taxes on business equipment to spur increased capital spending. Indiana's ranking on the Tax Foundation's business competitiveness index has risen to eighth-highest in the nation.

Comparing Republicans and Democrats

Supporters of smaller government lament that politicians of both major parties tax and spend too much. While that is true, Cato report cards have found that Republican governors are more fiscally conservative, on average, than Democratic governors. In the 2008 report, Republican and Democratic governors had average scores of 55 and 46, respectively. In the 2010 report, they had average scores of 55 and 47. In the 2012 report, they had average scores of 57 and 43. In the 2014 report, they had average scores of 57 and 42.

That pattern continues in the 2016 report card. This time, Republican and Democratic governors had average scores of 54 and 43, respectively. And, on average, Republicans received higher scores than Democrats on both spending and taxes.

Three of the 10 F grades on this report went to Republicans, but none of the five A grades went to Democrats. When states develop budget gaps, Democratic governors often pursue tax increases to regain budget balance, while Republicans tend to pursue spending restraint. And when the economy is growing and state coffers are full, Democrats increase spending, while Republicans tend to both increase spending and pursue tax cuts.

Fiscal Policy Trends

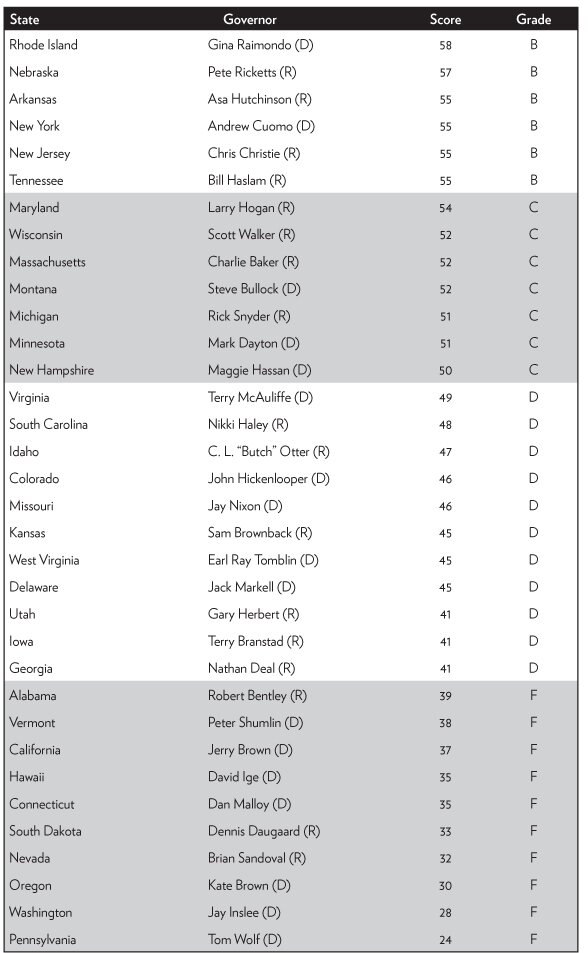

Figure 1 shows state general fund spending since 2000, based on data from the National Association of State Budget Officers.2 Spending soared between 2002 and 2008, and then it fell during the recession as states trimmed their budgets.3 Spending has bounced back strongly in recent years, growing 4.1 percent in 2013, 4.6 percent in 2014, 4.1 percent in 2015, 5.6 percent in 2016, and a projected 2.5 percent in 2017.

Figure 1. State General Fund Spending

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, "Fiscal Survey of the States," Spring 2016. Fiscal years.

A key driver of state spending growth is Medicaid. This giant program pays for health care and long-term care for 67 million people with moderate incomes.4 The program is funded jointly by federal and state taxpayers. It is the largest component of state budgets, accounting for 26 percent of total spending.5

Medicaid has grown rapidly for years, and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) expanded it even more.6 For states that implement the ACA's expanded Medicaid coverage, the federal government is paying 100 percent of the costs of through 2016, and then a declining share after that. As the federal cost share declines, state budgets will be put under more stress. But aside from the federal portion of Medicaid, the state-funded portion of the program is also growing quickly and stressing budgets. State-funded Medicaid spending grew 6.0 percent in 2015 and an estimated 8.3 percent in 2016.7

On the revenue side of state budgets, policymakers have been enacting a mix of tax cuts and tax increases. Overall, the states enacted a modest net tax cut in 2014 and 2015, but they swung to a net tax increase in 2016.8 Cigarette tax increases have been common, with a dozen states enacting them since 2014.9 Gasoline tax increases have also been common, with about half the states enacting them since 2013.10

There is also a trend toward reductions in individual and corporate income tax rates. There have been substantial rate cuts in Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, and Oklahoma in recent years. In some states, the revenues from income tax cuts have been partly offset with revenue increases from higher retail sales taxes.

These income tax reforms are good news, and they should help spur growth by making states more attractive for investment. However, there is also bad news regarding state efforts to attract investment, which is the proliferation of narrow tax breaks and subsidies for particular companies and industries. The classic example of such "corporate welfare" is the film production tax credits that most states now offer.

The 2014 Cato governors report card discussed why narrow business tax breaks and subsidies are bad policy, and research for this 2016 report confirmed that such breaks are rampant. Consider Nevada's recent tax policy. Governor Brian Sandoval imposed a huge $600 million per year tax increase on businesses, including higher license fees, an increase in the state's Modified Business Tax, and the imposition of a new Commerce Tax. At the same time, Sandoval has been eagerly handing out narrow tax breaks to Tesla, Amazon, data center companies, and other favored businesses. So Nevada's tax policy entails large increases for all businesses, but special breaks for companies favored by the politicians. That is a prescription for corruption, not long-term economic growth.

Longer-Term Outlook

This report card focuses on the short-term taxing and spending decisions of the governors. But a full assessment of a governor's performance should also examine his or her policies affecting long-term fiscal health. This section looks at state debt levels, unfunded pension obligations, and unfunded retirement health obligations, and ranks the states based on those fiscal measures.

State and Local Debt

State and local governments are major investors in infrastructure, including highways, bridges, and schools and other facilities. A portion of this investment is financed by long-term borrowing, or the issuance of state and local bonds. The interest and principal on government bonds is paid back over time from either taxes or user fees. State and local governments have been issuing debt for infrastructure since at least 1818, when New York floated bonds to finance the Erie Canal.

However, debt is not the only way to fund infrastructure. Indeed, most state infrastructure investment is financed on a pay-as-you-go basis.11 That approach entails governments looking ahead and planning to construct needed facilities over time with an allocated portion of annual tax revenues.

Pay-as-you-go financing is generally preferable to debt financing. The Erie Canal was a big success, and it is thought to have generated positive economic returns. But that success spurred many other states at the time to borrow heavily and spend lavishly on their own, more dubious, canal schemes. State politicians in the mid-19th century overestimated the demand for canals and underestimated the construction costs. It turned out that the Erie Canal was a uniquely high-return route, while most state-sponsored canals in the 19th century were money-losing failures.12

The failures of many debt-backed state projects in the 19th century led to sweeping budget reforms. Nineteen states imposed constitutional limits on state debt issuance between 1840 and 1855.13 Further constitutional limits on state and local debt were passed in the 1870s. The limits took numerous forms, including requiring voter approval of debt issuance, limiting overall quantities of debt, and limiting the purposes for which state debt can be issued.

Today, all state governments operate within statutory and/or state constitutional limits on debt. Limits make sense because politicians have an incentive to issue debt in excess: debt-financed investment is not constrained by the unpopular need to raise current taxes, as it is for pay-as-you-go investment. Political incentives to deficit-spend can create severe economic damage if debt reaches high levels, as we have seen recently in Greece, Puerto Rico, Detroit, and other jurisdictions.

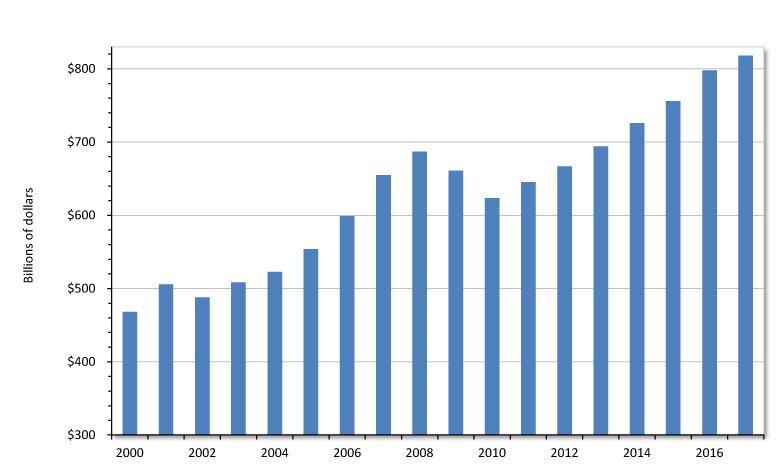

U.S. state and local government debt totaled $3 trillion in 2016.14 Table 2 shows that state and local debt per capita varies widely by state.15 The most indebted states by this measure are New York, Massachusetts, Alaska, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

Governments in some states, such as Idaho and Wyoming, issue very little debt. They finance most of their capital expenditures on a pay-as-you-go basis. These states have per capita debt loads only one-quarter as large as the highly indebted states, and thus governments in these states are imposing much lower costs on future taxpayers.

California's budget this year discusses how the state is painting itself into a corner with debt: "Budget challenges over the past decade resulted in a greater reliance on debt financing, rather than pay-as-you-go spending. . . . The increasing reliance on borrowing to pay for infrastructure has meant that roughly one out of every two dollars spent on infrastructure investments goes to pay interest costs, rather than construction costs. . . . Annual expenditures on debt service have steadily grown from $2.9 billion in 2000-01 to $7.7 billion in 2015-16."16 To politicians, debt might seem like an easy way to fund infrastructure, but the servicing costs eventually eat away at current budgets.

Debt financing costs more than pay-as-you-go financing because of the interest payments, but also because governments pay substantial fees to the municipal bond industry. State and local borrowing creates an overhead cost in the form of thousands of high-paid experts in underwriting, trading, advising, bond insurance, and related activities. A study by economist Marc Joffe found that fees average about 1 percent of the principal value of municipal bonds.17 Since municipal bond issuance has averaged about $350 billion a year recently, fees are about $3.5 billion a year. That is taxpayer money that is not going toward building highways or schools.

A further cost of borrowing is the risk of corruption. The municipal bond industry has suffered from many scandals related to political influence. If you Google "municipal bond market" and "pay-to-play," you will find story after story about bond underwriters using bribes and campaign contributions to win bond business from state and local officials.

Debt financing also makes government budgeting less transparent. Capital budgets that rely on debt are difficult for citizens to understand, especially given the myriad and complex ways that governments borrow these days. Also, citizens have less appreciation for the costs of new government projects if they do not feel the bite of current taxes to pay for them.

Perhaps the most important reason to worry about state debt is that other large fiscal burdens are looming over the states. Medicaid costs are growing rapidly, as noted. And retirement plans for government employees have large unfunded liabilities, as discussed next.

Table 2. State and Local Government Debt and Unfunded Pension and OPEB Liabilities (Dollars Per Capita, Ranked Highest to Lowest)

Sources: Author's calculations based on data from U.S. Bureau of the Census, "State Government Finances," www.census.gov/govs/state; Joshua D. Rauh, "Hidden Debt, Hidden Deficits," Hoover Institution, April 2016; and Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Caroline V. Crawford, "How Big a Burden Are State and Local OPEB Benefits?" Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, March 2016. The pension data from Rauh are the stated or official figures.

Pension Plans and Retiree Health Costs

The largest component of state and local government spending is compensation for 16 million employees.18 Total wages and benefits for state and local workers was $1.4 trillion in 2015, which accounted for 53 percent of all state and local spending.19

State and local workers typically receive more generous benefit packages than do private-sector workers. On average, retirement benefits for state and local workers cost $4.80 per hour, compared to $1.23 per hour for private-sector workers. Insurance benefits (mainly health insurance) for state and local workers cost $5.43 per hour, compared to $2.59 per hour for the private sector.20 Most state and local workers receive retirement health benefits, whereas most private-sector workers do not.

The costs of government pension and retirement health benefits are expected to rise rapidly in coming years. Governments have promised their workers generous retirement benefits, but most states have not put enough money aside to pay for them. As a consequence, state and local governments will either have to cut benefits in coming years or impose higher taxes.

Let's look at pensions first. Most state and local governments provide their workers with defined-benefit (DB) pensions. Governments pre-fund their DB plans, building up assets to pay future benefits when they come due. Unfortunately, governments have overpromised benefits and underfunded their plans, creating large funding gaps. Total benefits paid by the nation's more than 500 state and local pension plans are $260 billion a year and rising.21

In a recent study, Stanford University's Joshua Rauh found that state and local pension assets in 2014 were $3.6 trillion, liabilities were $4.8 trillion, and thus unfunded liabilities were $1.2 trillion.22 State and local pension plans have only enough assets to pay 75 percent of accrued benefits.

A study by Alicia Munnell and Jean-Pierre Aubry found similar results.23 They found that the average funding level of pension plans grew during the 1990s, peaked at more than 100 percent in 2000, and then fell to just 74 percent today. That average is quite low, and there are many plans with dangerously low funding. The State of Illinois, Illinois Teachers, and Illinois Universities systems, for example, all had funding levels of 43 percent or less. For the State of Illinois, pension spending soared from $1.1 billion in 2000 to $7.7 billion in 2015, which was a substantial share of the state's $35 billion general fund budget that year.24 Major reforms are needed in such plans to reduce spending and bring liabilities in line with assets.

Pension shortfalls are actually larger than these figures indicate. Those are the officially reported figures, but financial experts think that the discount rates used to report pension liabilities are too high. Higher discount rates reduce reported liabilities and create an overly optimistic picture of pension plan health.

In his study, Rauh recalculated pension plan funding using a 2.7 percent discount rate, rather than the official average rate of 7.4 percent. His recalculated unfunded liability jumps from $1.2 trillion to $3.4 trillion. Similarly, Munnell and Aubry found that their unfunded pension liabilities jumped to $4.1 trillion if plans are estimated using a 4 percent discount rate.25 Under that assumption, the funding level of state and local pension plans averages just 45 percent.

Which states have the most underfunded pensions? Table 2 ranks the states on unfunded state and local pension liabilities per capita using the stated or official figures from Rauh. The level of pension liabilities varies widely. The highest liabilities are in New Jersey, Illinois, Alaska, Kentucky, and Connecticut. Note that using Rauh's recalculated figures at the lower discount rate, the unfunded liabilities are two or more times higher for most states.

Greater media focus on pension plans in recent years has prompted many state and local governments to trim their unfunded liabilities. But a pension report from Pew Charitable Trusts found that still only about half of the states are contributing the full "actuarial required contributions" to their plans, with the result that "pension debt is continuing to increase in many states."26

A good reform would be for states to scrap their defined-benefit (DB) pension plans for new hires, and instead offer them defined-contribution (DC) plans. Defined-contribution plans reduce risks for taxpayers and are the dominant type of retirement plan in the private sector. Alaska and Michigan have adopted DC plans for new employees, and a number of states have moved to systems that are hybrids of DB and DC.

In addition to pension liabilities, there is another type of liability that looms over state budgets: other post-employment benefits (OPEB). The main component of OPEB is retirement health care coverage, which includes benefits for early retirees before Medicare kicks in at age 65 and supplemental benefits after Medicare kicks in. California, for example, pays 100 percent of retirement medical costs for state workers after they have put in just 20 years of service.27 Very few private companies offer such generous benefits.

Total annual OPEB benefits nationwide are about $18 billion, and the costs are rising quickly as health costs grow and the number of retirees increases. In California, the share of the state's general fund budget spent on retiree health costs nearly tripled from 0.6 percent in 2001 to 1.6 percent by 2016.28

Unlike pension benefits, most state and local governments have not pre-funded OPEB at all. Annual benefits are simply paid from the general fund budget. A few states have started to prefund OPEB, but for the nation as a whole, the funding ratio — assets-to-liabilities — of state and local OPEB plans is less than 10 percent.29

Fortunately, this imprudent approach to financing OPEB has started to change. An accounting rule change in 2007 required governments to calculate and disclose unfunded OPEB obligations.30 Governments must now account for OPEB as they do their pensions, which is by estimating the future stream of promised benefits, discounting to the present value, and comparing those liabilities to plan assets.

How large are OPEB liabilities? A 2016 study by Alicia Munnell and coauthors estimated that unfunded state and local OPEB liabilities were $862 billion in 2013.31 Pew put the number at $627 billion, but the figure calculated by Munnell and coauthors captures a broader universe of plans.32 These figures are the costs of unfunded benefits that have been already accrued. But without reforms, OPEB liabilities will continue to rise as workers accrue more retiree benefits every year.

Table 2 shows that unfunded OPEB liabilities vary widely by state. The largest liabilities are in Alaska, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Hawaii. OPEB liabilities also vary dramatically across local governments. When Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, people pointed to the city's $3 billion in unfunded pension liabilities, but finance expert Robert Pozen noted that it also had $6 billion of unfunded OPEB, which compounded the city's fiscal woes.33

To fix OPEB funding gaps, states are beginning to trim retirement health benefits. They can do so by increasing the age of eligibility, reducing the types of benefits provided, or increasing deductibles and copays for plan members. State and local governments have substantial legal flexibility in cutting health benefits for current workers and retirees, but less so with pension benefits.

Some local governments, and at least one state (Idaho), have ended retiree health benefits for new employees. Since the 2007 accounting change, the share of state and local government workers receiving retirement health benefits has fallen to about 70 percent.34 In the private sector, just 28 percent of medium and large businesses offer their retirees such benefits.35

In sum, state governments should reduce their retirement benefits to lighten the load on future taxpayers. Unfunded benefits are not just a problem for the future; they cause problems right now because credit rating agencies assign lower scores to states that have high debt and unfunded liabilities. Standard and Poor's says that they "differentiate states' credit quality by the status of their long-term liability profile."36 Lower credit ratings mean higher borrowing costs. So governors should make it a high priority to reduce their states' debt, pension, and OPEB liabilities.

Appendix A: Report Card Methodology

This study computes a fiscal policy grade for each governor based on his or her success at restraining taxes and spending since 2014, or since 2015 for governors entering office that year. The spending data used in the study come from the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), and in some cases, the budget documents of individual states. The data on proposed and enacted tax cuts come from NASBO, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and news articles in State Tax Notes and other sources.37 Tax-rate data come from the Tax Foundation, but is updated by the author for recent changes.38

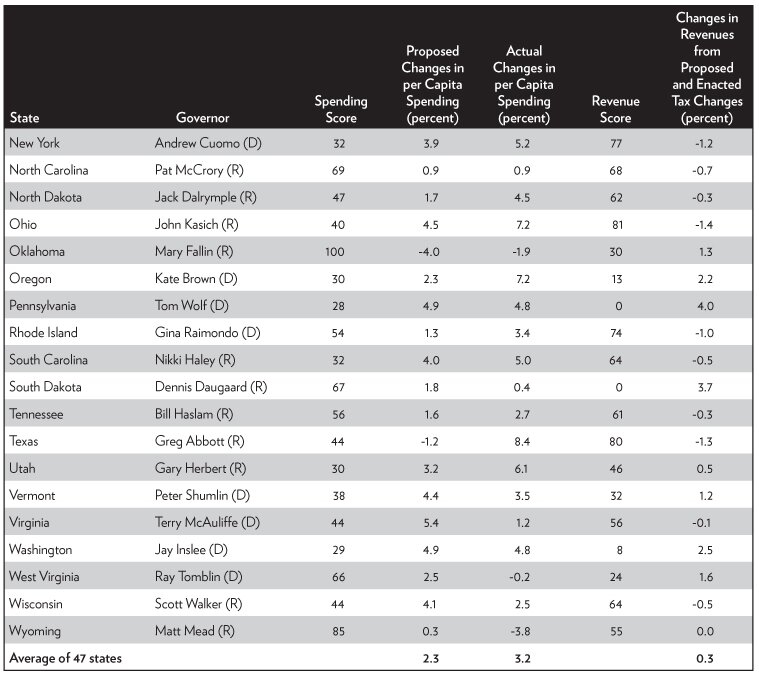

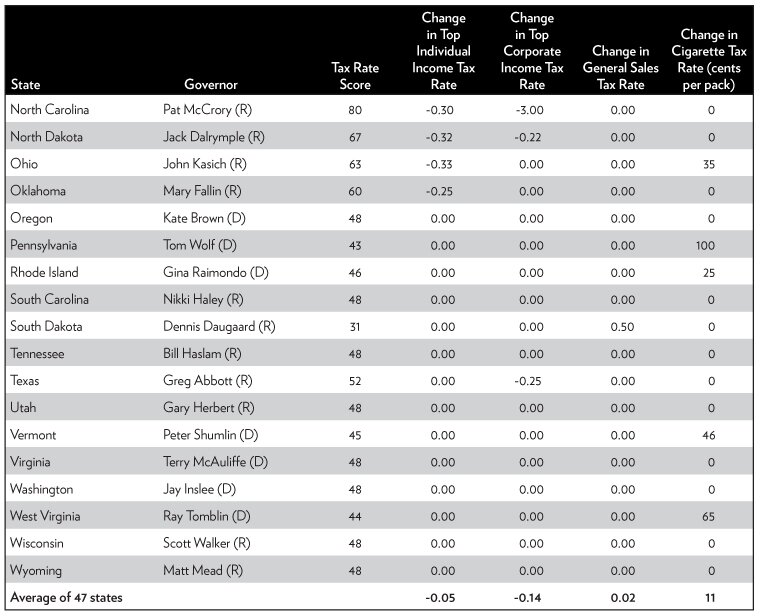

This year's report uses the same methodology as the 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014 Cato report cards. The report focuses on short-term taxing and spending actions to judge whether the governors take a small-government or big-government approach to policy. Each governor's performance is measured using seven variables: two for spending, one for revenue, and four for tax rates. The overall score is calculated as the average score of these three categories. Tables A.1 and A.2 summarize the governors' scores.

Spending Variables

-

Average annual percent change in per capita general fund spending proposed by the governor.

-

Average annual percent change in actual per capita general fund spending.

Revenue Variable

-

Average annual dollar value of proposed, enacted, and vetoed tax changes. This variable is measured by the reported estimates of the annual dollar effects of tax changes as a percentage of a state's total tax revenues. This is an important variable, and it is compiled from many news articles, budget documents, and reports.39

Tax Rate Variables

-

Change in the top personal income tax rate approved by the governor.

-

Change in the top corporate income tax rate approved by the governor.

-

Change in the general sales tax rate approved by the governor.

-

Change in the cigarette tax rate approved by the governor.

The two spending variables are measured on a per capita basis to adjust for state populations growing at different rates. Also, the spending variables are only for general fund budgets, which are the budgets that governors have the most control over. Variable 1 is measured through fiscal 2017, while variable 2 is measured through fiscal 2016. Variables 3 through 7 cover changes during the period of January 2014 to August 2016, or January 2015 to August 2016 for governors entering office in 2015.40

For each variable, the results are standardized, with the worst scores near 0 and the best scores near 100. The score for each of the three categories — spending, revenue, and tax rates — is the average score of the variables within the category. One exception is that the cigarette tax rate variable is quarter-weighted because that tax is a smaller source of state revenue than income and sales taxes. The average of the scores for the three categories produces the overall grade for each governor.

Measurement Caveats

This report uses publicly available data to measure the fiscal performance of the governors. There are, however, some unavoidable problems in such grading. For one thing, the report card cannot fully isolate the policy effects of the governors from the fiscal decisions of state legislatures. Governors and legislatures both influence tax and spending outcomes, and if a legislature is controlled by a different party, a governor's control may be diminished. To help isolate the performance of governors, variables 1 and 3 measure the effects of each governor's proposed, but not necessarily enacted, recommendations.

Another factor to consider is that the states grant governors differing amounts of authority over budget processes. For example, most governors are empowered with a line-item veto to trim spending, but some governors do not have that power. Another example is that the supermajority voting requirement to override a veto varies among the states. Such factors give governors different levels of budget control that are not accounted for in this study.

Nonetheless, the results presented here should be a good reflection of each governor's fiscal approach. Governors receiving an A have focused on reducing tax burdens and restraining spending. Governors receiving an F have put government expansion ahead of the public's need to keep its hard-earned money. In the middle are many governors who gyrate between different fiscal approaches from one year to the next.

Table A.1 Spending and Revenue Changes

Table A.2 Tax Rate Changes

Note: These are the tax rate changes since 2014 that were approved by the governors. It excludes the expiration of prior temporary changes. The changes are the actual changes in the rates. For example, Andrew Cuomo cut New York's corporate tax rate from 7.1 to 6.5 percent, so the table shows -0.60.

Appendix B: Fiscal Policy Notes on the Governors

Below are highlights of the fiscal records of the 47 governors covered in this report. The discussion is based on the tax and spending data used for grading the governors, as well as other information that sheds light on each governor's fiscal approach.41 Note that the grades are calculated based on each governor's record since 2014, or since 2015 if that was the governor's first year in office.

Alabama

Robert Bentley, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: F; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Robert Bentley dropped from a B in the last report card to an F in this one due to his support of major tax increases. In his first few years in office, Bentley generally opposed tax increases, but in 2015 he made a U-turn. He proposed a tax increase of more than $500 million a year, including increases on businesses, cigarettes, automobile sales, automobile rentals, and other items.

The governor's plan was opposed by the legislature, but after months of wrangling they reached a compromise on a $100 million tax package. Bentley signed into law a cigarette tax increase of 25 cents per pack, and higher taxes and fees on nursing facilities, prescriptions, and the insurance industry. In 2016 Bentley supported a gasoline tax increase, but that legislation did not pass.

On spending, Governor Bentley scored lower than average among the governors. He proposed substantial general fund budget increases the past two years.

Arizona

Doug Ducey, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: A; Took Office: January 2015

Doug Ducey has a background in business and finance, and he was CEO of Cold Stone Creamery. As governor, he has overseen lean budgets, with general fund spending on track to rise just 2 percent between 2015 and 2017. In 2016 Ducey approved major pension reforms, which included trimming benefit costs and giving new hires the option of a defined contribution plan.

Governor Ducey has signed into law individual and business tax cuts. He approved legislation ending sales taxes on some business purchases, reducing insurance premium taxes, increasing depreciation deductions, and indexing Arizona's income tax brackets for inflation. Ducey has also been supportive of the corporate tax rate cut passed by the prior governor, which is being phased in over time. The corporate tax rate is falling from 7 percent in 2013 to 4.9 percent in 2017.

Arkansas

Asa Hutchinson, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2015

Former U.S. Representative and federal official Asa Hutchinson entered the Arkansas governor's office in January 2015. Hutchinson campaigned on a middle-class tax cut, and he delivered soon after taking office. He signed into law a cut to tax rates for households with incomes of less than $75,000, providing savings of about $90 million a year.42 The governor said, "Arkansas has been an island of high taxation for too long, and I'm pleased that we are doing something about that."43 Enjoying substantial budget surpluses in 2016, Hutchinson has promised further tax cuts. On spending, Hutchison scored a bit better than average among the governors.

California

Jerry Brown, Democrat; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: F; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Jerry Brown was graded as the worst governor in America on the 2014 Cato report card. Brown is not the lowest-scoring governor this time, but he is assigned another F based on his support of large tax and spending increases.

California's general fund budget increased 13 percent in 2015 and 2.7 percent in 2016, and it is set to increase more than 5 percent in 2017. The state has been on a hiring spree, with state government employment rising 7 percent over the past three years.44

Perhaps Brown's most wasteful spending project is on the state's high-speed rail system, which has a huge cost but will do little to reduce congestion. The projected cost of the project has doubled from $33 billion to $68 billion. An investigation in 2016 discovered that taxpayers will be on the hook not only for the project's capital costs, but also its operating costs.45 State officials had been promising that passenger ticket revenues would cover operating costs, but it is clear now that will not happen.

On taxes, Brown has pushed a transportation plan to raise $3 billion a year from higher gasoline and diesel taxes and a $65 per vehicle annual fee. Luckily for California motorists, the plan has not passed, although the legislature did approve a small vehicle registration fee increase in 2016.

Californians have been spared major tax increases the past couple of years because money has poured into state coffers from growth in Silicon Valley and other regions in the state. However, the next recession will cause the California budget to descend into crisis, as it has during past recessions. That occurs because California tax revenues are highly dependent on high earners and capital gains. As the stock market faltered earlier this year, for example, state revenue projections were slashed by $2 billion.46 If the California economy slumps, the budget will not be able to support the extra spending that Brown has added in recent years.

Brown recognizes these problems. In 2016 he noted of the state's tax system: "We are taxing the highest income earners, and as you know, 1 percent of the richest people pay almost half the income tax. . . . That's fair, but it also creates this volatility. So in order to manage this budget, it's like riding a tiger."47 Brown has favored building up the state's rainy-day fund, but he has not supported reforms to reduce revenue volatility, such as moving toward a more stable consumption-based tax system.

This November, voters will decide on various ballot measures on taxes. One measure would raise $1 billion a year from a cigarette tax hike of $2 per pack. Another measure would extend higher income tax rates on households earning more than $250,000 a year. And yet another measure will ask voters to legalize recreational marijuana. There would be a 15 percent excise tax on retail sales and a separate cultivation tax, which would together raise about $1 billion a year.48

Colorado

John Hickenlooper, Democrat; Legislature: Divided

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2011

General fund spending has ballooned under Governor John Hickenlooper, rising 48 percent between 2011 and 2016. State government employment has soared 22 percent since Hickenlooper took office.49

Hickenlooper pushed for a large individual income tax increase on the ballot in 2013, which would have replaced Colorado's flat-rate 4.63 percent tax with a two-rate structure of 5.0 and 5.9 percent. That increase was rejected by voters, 65 to 35 percent.50 The governor has not pushed for major tax increases since then, but with a growing economy, revenues have poured into state government.

The state has a new source of revenue: marijuana. After citizens legalized the drug for recreational use on a 2012 ballot, Colorado has become "the first state in history to generate more annual marijuana tax revenue than alcohol tax revenue. . . . The state collected $69.9 million from marijuana-specific taxes in fiscal 2015 and just under $41.8 million from alcohol specific taxes in the same period."51

While not pushing major tax increases in recent years, Hickenlooper has opposed taxpayer interests by seeking to undermine the state constitution's Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR). TABOR requires voter approval of tax increases and requires the government to refund excess taxes above an annual revenue cap. Revenues have been exceeding the cap recently, which is "prompting Gov. John Hickenlooper (D) and Democrats in the legislature to look for ways around the law."52

Connecticut

Dan Malloy, Democrat; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: F; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Dan Malloy received poor grades on prior Cato report cards due mainly to his enormous tax increases. In 2011 Governor Malloy raised taxes by $1.8 billion annually, which increased total annual state tax collections by 14 percent.

Malloy received an F on this report for his continued support of large tax increases. In 2015 he signed legislation increasing taxes more than $900 million annually. He increased the top individual income tax rate from 6.7 percent to 6.99 percent, and he extended a corporate income tax surcharge of 20 percent. He increased the cigarette tax by 50 cents per pack and broadened the bases of the sales tax and income tax. He also increased health provider taxes and other taxes and fees.

Despite all the tax increases, Connecticut still faced a large budget gap in 2016 because spending keeps rising and growth is sluggish. Connecticut's economy has lagged the national economy, and the state's fiscal future is very troubled. It has some of the highest debt and unfunded retirement liabilities of any state on a per capita basis, as discussed above.

While neighboring New York has cut business taxes in recent years, Connecticut has raised them. In 2016 General Electric made headlines by moving its headquarters from Connecticut to Massachusetts. In 2015 GE head Jeffrey Immelt sent a letter to his employees saying that the company was looking to relocate "to another state with a more pro-business environment."53 GE announced in 2016 that it was moving to Boston, after being headquartered in Connecticut for more than 40 years.

Delaware

Jack Markell, Democrat; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2009

Former businessman Jack Markell is completing his second term as Delaware governor. He has scored fairly poorly on past Cato report cards. He signed into law large "temporary" tax increases in 2009, and then pushed to extend them in 2013. The top individual income tax rate was increased from 5.95 percent to 6.6 percent, where it remains today. In 2014 Markell signed into law a substantial increase in the corporate franchise tax, and he proposed a 10 cent per gallon gas tax increase and a new tax on water service. In 2015 he approved increases in various motor vehicle fees. In 2016 Markell approved modest business tax reductions.

Florida

Rick Scott, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: A; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Rick Scott received an A on Cato's 2012 report, and he receives an A on this report for restraining spending and continuing to push for tax cuts. Scott often says that his goal is to make Florida the best state for business in the nation, and tax cuts are a key part of his strategy.

In 2012 Scott raised the exemption level for the corporate income tax, eliminating the burden for thousands of small businesses. In 2013 he approved a temporary elimination of sales taxes on manufacturing equipment. In 2014 he signed into law a $400 million cut to vehicle fees and proposed a further increase in the corporate tax exemption level.

In 2015 Scott approved a large cut to the state's tax on communication services and modest reductions in sales and business taxes. In 2016 he proposed more than $900 million in tax relief, including a cut to the sales tax on commercial rents and a full exemption for manufacturers and retailers from the corporate income tax.54 The legislature did not approve those two proposals, but it did pass Scott's plan to permanently eliminate sales taxes on manufacturing equipment, which is a solid pro-growth reform.

Governor Scott scored well on spending in this report. He has proposed low-growth general fund budgets the past three years. State government employment has been cut 4 percent under Scott.55

Georgia

Nathan Deal, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Nathan Deal earned a D due to his poor performance on both spending and taxes. Georgia's general fund budget grew 27 percent between 2011 and 2016, and Deal proposed a substantial increase for 2017.

With regard to taxes, Deal supported a ballot measure in 2012 to increase sales taxes, but voters shot that plan down by a large margin.56 In 2015 Deal signed into law a large increase in gasoline taxes, hotel taxes, and other levies to raise more than $600 million a year. In general, Deal has favored raising broad-based taxes and shown little interest in major tax reform. Meanwhile, he has pushed narrow breaks for favored industries and companies, such as tax credits for the film industry and an exemption for major sports team tickets from the sales tax.

Hawaii

David Ige, Democrat; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: F; Took Office: January 2015

Before being elected governor, David Ige was a state legislator and also an engineer and manager in the telecommunications industry. Ige defeated incumbent Hawaii governor Neil Abercrombie in the Democratic primary in 2014. Abercrombie had received poor grades on Cato reports, and Ige pointed to his tax hikes as one of the causes of his political demise.57

Ige let expire temporary income tax increases put in place by Abercrombie, but he proposed increases in gasoline taxes and vehicle registration fees in 2016. However, it was the governor's excessive spending that pushed down his grade on this report. General fund spending rose 7 percent in 2016, and Ige proposed to increase it 12 percent in 2017.

Idaho

C. L. "Butch" Otter, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2007

Former congressman Butch Otter is in his third term as Idaho governor. He has a moderately pro-growth record on taxes, but a poor record on spending.

In 2012 he signed legislation cutting the corporate tax rate from 7.6 to 7.4 percent and the top individual income tax from 7.8 to 7.4 percent. In 2015 he proposed cutting income tax rates further, to 6.9 percent, over five years. He also proposed ending property taxes on business equipment, which would have been a pro-growth reform. However, Otter did not push these cuts very hard, and they did not get passed.

In 2015 the governor approved a 7 cent per gallon increase in the gasoline tax. In 2016 Otter said that he was against tax cuts that were being considered by the legislature because they would jeopardize his spending priorities.58

Otter scores poorly on spending in this report. The general fund budget increased 5.6 percent in 2015 and 4.6 percent in 2016. He proposed a 7.3 percent increase for 2017.

Illinois

Bruce Rauner, Republican; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2015

Businessman Bruce Rauner took office as Illinois governor in January 2015 eager to fix his state's severe fiscal problems. Unfortunately, Rauner and the state legislature have been at loggerheads, and so budgeting has mainly ground to a halt the past two years.

The good news for Illinois is that Rauner replaced Pat Quinn, a repeated F governor on Cato reports. It is also good news that large personal and corporate income tax increases passed under Quinn have expired as scheduled. Furthermore, the budget standoff has meant that state general fund spending has been flat since 2014.

The bad news is that Illinois has not tackled its serious fiscal problems, including large structural deficits and unfunded pension obligations. Quinn's temporary tax increases had raised about $6 billion a year for the state, which the government quickly became dependent on as spending rose. When the extra tax revenue disappeared in 2015, large deficits reappeared.

In 2015 Rauner proposed a state budget that partly closed the gap between spending and revenues, and the legislature responded with an even more unbalanced budget. Rauner vetoed the legislature's budget, and the state was in a stalemate until June 2016, when a compromise deal was finally signed.

Rauner had said that he would not agree to higher taxes unless the legislature agreed to some of his Turnaround Agenda, which includes worker compensation reform and lawsuit reform. In a 2016 address, Rauner said, "I won't support new revenue unless we have major structural reforms to grow more jobs and get more value for taxpayers. . . . I'm insisting we attack the root causes of our dismal economic performance."59 In the end, a deal was struck that did not include Rauner's reforms, but it also did not give the legislature the extra taxes and spending that it wanted.60

During the budget standoff, the state built up IOUs to businesses providing services to the government. That fits with the state's pattern of pushing its costs to the future. Table 2, above, showed that Illinois is near the top of the 50 states in terms of per capita debt, unfunded pensions, and unfunded OPEB. These problems have been building for years — the underfunding of state pensions, for example, has roots two decades old.61 Rising pension spending is exacerbating budget gaps — pension spending soared from $1.1 billion in 2000 to $7.7 billion in 2015, which is a large share of the $35 billion Illinois general fund budget.62

Governor Rauner is trying to put the state on a more business-like posture, but he is receiving little help from the legislature. In his 2016 State of the State speech, he argued that Quinn's large tax increases hurt the state's economic growth, and he noted that the state's credit rating was downgraded five times during the high-tax Quinn years.63

Indiana

Mike Pence, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: A; Took Office: January 2013

Governor Mike Pence has been a champion tax cutter and fairly frugal on spending. In 2013 he signed into law a cut to Indiana's flat individual income tax rate from 3.4 percent to 3.23 percent. He also approved a repeal of Indiana's inheritance tax.

In 2014 he cut the corporate income tax rate, adding to the reductions made by prior governor Mitch Daniels. The rate has fallen from 7.5 percent to 6.25 percent since 2014 and is scheduled to fall to 4.9 percent by 2021.64 Pence also targeted property taxes on business equipment for reform, and in 2014 he signed off on a plan to allow local governments to cut these anti-investment levies. These and other changes have helped Indiana increase its ranking among the states on the Tax Foundation's competitiveness index to 8th-highest this year.65

At the same time, Pence has restrained state spending growth. The general fund budget increased 2.6 percent in 2015 and 1.1 percent in 2016. It is set to grow 3.0 percent in 2017. Under Pence, Indiana has maintained the top credit rating from the three main credit rating agencies.

Iowa

Terry Branstad, Republican; Legislature: Divided

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2011

Terry Branstad was governor of Iowa for 16 years between 1983 and 1999, and he returned to the governorship in 2011. His main pro-growth fiscal reform was a large property tax cut in 2013. The reform created a growth cap for agriculture and residential assessments, reduced assessment levels for commercial and industrial property, and cut property taxes for small businesses.

In recent years, Branstad has cut some taxes and increased others. He cut sales taxes on inputs to manufacturing and approved other modest business tax breaks. He also created a system of income tax rebates for years with budget surpluses. However, Branstad also approved a 10 cent per gallon gas tax increase, which raised more than $200 million annually.

On spending, Branstad has performed poorly. He came into office promising to cut the size of state government by 15 percent, but instead general fund spending has soared. Spending has increased 11 percent in the past two years, and has increased 34 percent since he took office in 2011.

Kansas

Sam Brownback, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Sam Brownback signed into law major income tax reforms his first few years in office. In 2012 he replaced individual tax rates of 3.5, 6.25, and 6.45 percent with rates of 3.0 and 4.9 percent. The reform increased standard deductions and eliminated special-interest breaks. In 2013 Brownback cut income tax rates further, while reducing income tax deductions and raising the sales tax rate from 5.7 to 6.15 percent.66

Brownback's tax cuts have become controversial. The problem is that the governor and legislature did not fully match the reduced revenues with reduced spending, which created chronic budget gaps. The fairly slow-growing economy in Kansas has not helped matters.

The governor has taken steps to reduce budget gaps. In 2015 he raised the sales tax rate from 6.15 percent to 6.5 percent, increased the cigarette tax by 50 cents per pack, and reduced deductions under the individual income tax.67 The 2015 package raised about $300 million a year.

Those large tax increases pushed down Brownback's grade on this report, but his relatively frugal spending kept his grade out of the basement. Kansas general fund spending increased less than 10 percent between 2011 and 2016, and is expected to increase just 1 percent in 2017.68

Brownback's reforms do not illustrate that state tax cuts are a bad idea, as some pundits have suggested. In most states in most years, government revenues grow as the economy grows. Well-designed reforms, phased in over time, let taxpayers keep some of that growth dividend, and that can be achieved within a balanced-budget framework if spending is trimmed. Brownback's basic reform idea — to cut income tax rates in exchange for sales tax increases — should strengthen the Kansas economy over the long term since sales taxes are less harmful than income taxes.

The challenge for tax-cutting states is to ensure that policymakers fully match tax cuts with spending cuts. Both strengthen the economy, and both are needed to meet state balanced-budget requirements. Brownback has worked to close budget gaps, and in 2016 he proposed various savings options, including across-the-board spending cuts.

Maine

Paul LePage, Republican; Legislature: Divided

Grade: A; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Paul LePage has been a staunch fiscal conservative. He has held down general fund spending in recent years, and he has cut state government employment 9 percent since he took office.69 LePage has signed into law cost-cutting reforms to welfare and health programs, and he has decried the negative effects of big government: "Big, expensive welfare programs riddled with fraud and abuse threaten our future. Too many Mainers are dependent on government. Government dependency has not — and never will — create prosperity."70

LePage has been a persistent tax cutter. In 2011 he approved large income tax cuts, which reduced the top individual rate, simplified tax brackets, and reduced taxes on low-income households. He also increased the estate tax exemption, cut business taxes, and halted automatic annual increases in the gas tax.

In 2013 LePage vetoed the legislature's budget because it contained tax increases, including an increase in the sales tax rate from 5.0 to 5.5 percent. However, his veto was overridden by the legislature.

In 2015 the Maine budget process broke down. LePage proposed a plan to reduce the top individual income tax rate from 7.95 to 5.75 percent, reduce the top corporate tax rate from 8.93 to 6.75 percent, eliminate narrow tax breaks, repeal the estate tax, and raise sales taxes.71

When the legislature rejected the plan, LePage said that he would veto any bills sponsored by Democrats. In the end, the legislature passed a budget that included substantial tax cuts over the veto of LePage, who wanted larger cuts. The plan cut the top personal income tax rate from 7.95 to 7.15 percent, reduced taxes for low-income households, increased the estate tax exemption, and made the prior sales tax rate increase permanent.

In 2016 LePage pushed for more tax cuts. In his State of the State address, he proposed reducing the individual income tax rate to 4 percent over time and repealing the estate tax. Over the years, he has also called for abolishing the state income tax altogether.

While LePage is a strong fiscal conservative, his political combativeness sometimes gets the better of him. In 2016 he even challenged one legislator to an old-fashioned duel, although he later apologized. Surely, the governor would better accomplish his fiscal policy goals by putting aside his anger and trying to work cooperatively with state lawmakers.

On the November ballot, Maine voters will face two questions affecting taxes. Question 1 would legalize marijuana and impose on it a sales tax of 10 percent. Question 2 would impose higher income taxes on households earning more than $200,000 a year. LePage opposes both ballot initiatives.

Maryland

Larry Hogan, Republican; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2015

Larry Hogan won an upset victory in November 2014 in this Democratic-leaning state. Governor Hogan has gained a high favorability rating in polls, and he has nudged Democrats in the legislature toward spending restraint and tax relief. In one popular move, he repealed the "rain tax," which was a new stormwater fee enacted by the prior governor. Another popular move by Hogan has been to use his executive authority to cut highway tolls and fees for many state services.

In 2016 Hogan proposed a package of tax cuts for families and businesses. The plan would have reduced taxes on seniors and low-income families, and also reduced business fees. Furthermore, it would have cut taxes on manufacturers, but in a complex way. New manufacturing firms in some regions would be exempt from the income tax for 10 years, and employees of those firms would also get tax breaks. The legislature did not pass the plan, and such micromanagement of tax relief is misguided. Hogan should instead focus on cutting taxes broadly by dropping Maryland's 8.25 percent corporate income tax rate.

Massachusetts

Charlie Baker, Republican; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2015

After a career in the health care industry and state government, Charlie Baker was elected Massachusetts governor in November 2014. The governor is viewed as being socially moderate and fiscally conservative, and he is enjoying high popularity ratings.

In running for office, Baker said that he would not raise taxes, and he has stuck to that promise so far. The state income tax rate dropped slightly in 2015 and 2016 after budget targets were met, and the governor was supportive of those reductions.

The Massachusetts constitution requires that the state income tax be levied at a flat rate, currently 5.1 percent. But the legislature has been talking about amending the constitution and imposing a "millionaire tax." Baker opposes that idea, and the public likely supports him. Residents of Massachusetts have voted against imposing a graduated income tax five times since 1960.72

A 2014 ballot measure repealed automatic increases in the state's gas tax. In supporting that change, Baker said, "I'm not talking taxes, period. Not talking taxes, because as far as I'm concerned we have a long way to go here to demonstrate to the public, to each other and to everybody else that this is a grade-A super-functioning [highway department] machine that's doing all the things it should be doing."73

The spending side of the budget is where Baker's grade is pulled down a bit. The general fund budget rose 6.1 percent in 2016.

This November, Massachusetts will vote on a ballot question to legalize recreational marijuana, and to impose the state sales tax plus a 3.75 percent excise tax on the product. Governor Baker opposes the initiative.

Michigan

Rick Snyder, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2011

After a successful business career, Rick Snyder came into office eager to solve Michigan's deep-seated economic problems. The governor has pursued important reforms, such as restructuring Detroit's finances and signing into law right-to-work legislation. He repealed the damaging Michigan Business Tax and replaced it with a less harmful corporate income tax. In 2014 he pushed through a large reduction in property taxes on business equipment, which should help spur capital investment. The cut was approved by Michigan voters in August 2014.

In 2015 he signed into law a mechanism that will automatically decrease state income taxes whenever general fund revenue growth exceeds inflation by a certain percentage. Unfortunately, the mechanism does not kick in until 2023.

Snyder's grade was pulled down by his tax increases to fund transportation. In 2015 he increased gasoline taxes from 19 to 26.3 cents per gallon and vehicle fees by 20 percent. Those hikes will cost taxpayers about $600 million a year. Snyder and the legislature pushed through the package despite Michigan voters having rejected by an 80-20 margin a sales and gas tax increase for transportation on a May 2015 referendum (Proposal 1). That "rejection was the most one-sided loss ever for a proposed amendment to the state constitution of 1963."74 Yet later in 2015, Snyder and the legislature hiked taxes for transportation anyway.

Minnesota

Mark Dayton, Democrat; Legislature: Divided

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Mark Dayton has rebounded from his prior Cato grade of "F." His poor grade had stemmed from large tax hikes, including raising the top individual income tax rate and raising cigarette taxes. The cigarette tax rate is now indexed and rises automatically every year. In 2014 Dayton reversed course and signed into law tax cuts totaling about $500 million a year, including reductions to income taxes, estate taxes, and sales taxes on business purchases.

But during 2015 and 2016, Dayton proposed various options to raise about $400 million a year from increases in gasoline taxes and vehicle registration fees. Those proposed increases did not pass the legislature.

With a substantial budget surplus developing in 2016, Republicans in the legislature proposed major tax cuts. One reform would have substantially reduced property taxes on business equipment. It seemed as if Dayton might reach some compromise with the legislature on a package of cuts, but the bill that passed the legislature included a drafting error and Dayton refused to sign it.

Mississippi

Phil Bryant, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2012

Until this year, Governor Phil Bryant had been a modest tax cutter. He had trimmed some business taxes and repealed motor vehicle inspection fees. But in 2016 he signed into law major tax cuts for businesses and individuals that were initiated by the legislature. The most important reform was phasing out over 10 years the corporate franchise tax, which is imposed on businesses in addition to the state's corporate income tax.75 This reform was a priority of the Senate Finance Committee chairman, who said that the franchise tax "puts us at an economic disadvantage [and] . . . is really an outdated form of tax."76 Governor Bryant was hesitant to cut the franchise tax, but in the end he did sign this important reform.

The 2016 tax package included other reductions. It cut taxes for self-employed individuals and cut the bottom individual income tax rate from 3 percent to zero, which provided across-the-board savings. Bryant had wanted to swap income tax cuts for a gas tax increase, but the legislature did not go along with the gas tax idea.

Missouri

Jay Nixon, Democrat; Legislature: Republican

Grade: D; Took Office: January 2009

Governor Jay Nixon has battled the legislature over taxes for years. In 2013 the legislature passed an $800 million tax cut that would have reduced corporate and individual income tax rates. Nixon vetoed the bill, and the legislature was unable to override. In 2014 the legislature tried again and passed a bill over Nixon's veto. The package of tax cuts reduced the top individual income tax rate from 6.0 to 5.5 percent, and it provided a 25 percent deduction for business income on individual returns. The cuts are to be phased in beginning in 2017. However, they are contingent on state revenue targets being met, and they had not been met as of mid-2016.

Montana

Steve Bullock, Democrat; Legislature: Republican

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2013

Governor Steve Bullock scored well on spending in this report. But his grade was pulled down by his repeated vetoes of tax reform plans passed by the legislature. One plan he vetoed in 2015 would have trimmed the corporate tax rate, reduced the number of individual income tax brackets, raised the standard deduction and personal exemption, and scrapped narrow breaks in the code to simplify the system.

Bullock has approved at least one substantial reform, which was a 2013 law that reduced property taxes on business equipment. Bullock's Republican challenger for the governorship in 2016 is calling for further reductions in property taxes on business equipment, as well as individual income tax cuts.

Nebraska

Pete Ricketts, Republican; Legislature: Nonpartisan

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2015

Pete Ricketts is an entrepreneur and former executive with TD Ameritrade. He is a conservative who favors tax reductions and spending restraint.

In 2015 Governor Ricketts vetoed a 6 cent per gallon gas tax increase, arguing that the state should solve its infrastructure challenges without tax hikes. The legislature overrode him to enact the increase.

In running for governor, Ricketts campaigned on property tax reduction, and he signed into law relief for homeowners, businesses, and farms in the form of state credits for local taxes. In 2015 the legislature considered various proposals for major income tax reform. Governor Rickets is favorably disposed toward such reforms, but no plan has passed the legislature yet.

Nevada

Brian Sandoval, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: F; Took Office: January 2011

Brian Sandoval came into office promising no tax increases. But Governor Sandoval made a U-turn in 2015 and signed into law the largest package of tax increases in Nevada's history at more than $600 million per year. The package included a $1 per pack cigarette tax increase, extension of a prior sales tax hike, an increase in business license fees, a new excise tax on transportation companies, and an increase in the rate of Nevada's existing business tax, the Modified Business Tax (MBT).

However, the worst part of the package was the imposition of a whole new business tax in Nevada, the Commerce Tax.77 This tax is imposed on the gross receipts of all Nevada businesses that have revenues of more than $4 million a year. The new tax has numerous deductions and 27 different rates based on the industry, and it interacts with the MBT.

The Commerce Tax is complex, distortionary, and hidden from the general public. As a gross receipts tax, it will hit economic output across industries unevenly, and it will likely spur more lobbying as industries complain that their tax burdens are higher than other industries. Imposing the tax was a major policy blunder.

The Commerce Tax was imposed to increase funding for education. But Sandoval and the legislature had been directly rebuked by the public in 2014 for their effort to impose a new tax for education. In a November 2014 ballot, Nevada voters overwhelming rejected by a 79-21 margin the adoption of a new franchise tax to fund education.

Meanwhile, in recent years Sandoval and the legislature have been handing out narrow tax breaks to electric car companies, data centers, and other favored businesses. In 2014, for example, Sandoval approved a deal to provide $1.25 billion in special tax breaks and subsidies over 20 years to car firm Tesla. So Nevada's tax policy entails large increases for all businesses, but narrow breaks for the lucky few.

This November, Nevada voters will weigh in on a ballot question, Question 2, to legalize recreational marijuana and impose the state sales tax and a 15 percent excise tax on the product. Governor Sandoval opposes legalization.

New Hampshire

Maggie Hassan, Democrat; Legislature: Republican

Grade: C; Took Office: January 2013

Governor Maggie Hassan received a middling grade on this report, as she did on the 2014 report. She performed below average on spending, highlighted by a 7 percent increase in the general fund budget in 2016. On taxes, Hassan has signed into law a mix of increases and cuts. In 2013 she proposed a cigarette tax increase of 30 cents a pack, and the legislature agreed to 10 cents. In 2014 she approved a gasoline tax increase of 4.2 cents per gallon.

In 2015 Hassan reversed course and cut taxes after she initially resisted. She approved small rate cuts to the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax, and she increased the research tax credit. Those changes were a compromise with the legislature after the governor's veto of an initial tax-cut package. The compromise plan includes a second round of tax cuts in 2019 if state revenues hit specified targets.

In 2016 Hassan signed bills increasing business depreciation deductions and repealing a tax that had been imposed on stock offerings.

New Jersey

Chris Christie, Republican; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2010

New Jersey has struggled with a sluggish economy, budget gaps, and a large unfunded retirement obligation for state workers. In 2016 the state had to deal with a budget gap when revenue projections were reduced by $1 billion. The state treasurer argued that revenues are volatile because they depend heavily on the incomes of high earners: "Our progressive tax code makes us far too reliant upon extraordinary sources of income from our highest income earners."78 To reduce volatility and spur economic growth, the state should move away from income taxes and toward sales taxes in its revenue base.

Governor Chris Christie has tried to reduce income taxes. He signed into law substantial business tax cuts in 2011, and he has proposed across-the-board individual income tax cuts. He has repeatedly vetoed income tax hikes passed by the legislature, insisting that "income taxes being raised in any way, shape or form will not happen while I'm governor — under no circumstances."79

In 2016 he said raising taxes would be "insanity" and called for lower taxes to "stop people from leaving New Jersey."80 The New York Times profiled one New Jersey billionaire who moved to Florida in 2016 and single-handedly appears to have cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars in lost tax revenues.81 In his 2016 State of the State address, Christie called for elimination of the state's estate tax: "Our tax structure incentivizes people to move to other states as they age, and when they do they take their businesses and capital with them."82

Christie and the legislature struggled for months this year to agree on a deal to raise the gasoline tax 23 cents per gallon in return for cutting the estate tax and possibly the sales tax. As of August, Christie, the House, and the Senate could not come to an agreement.

Christie scored quite well on spending in this report, with below average increases in the general fund budget in recent years. State government employment has been cut 5 percent since Christie took office.83

Major fiscal problems loom for New Jersey. The state has one of the lowest credit ratings, partly as a result of its large unfunded retirement obligations. Reflecting on a negative assessment from Standard and Poor's in 2016, Bloomberg noted, "New Jersey's mounting tab from its employee retirement plans are squeezing its finances because years of failing to set aside enough to cover promised benefits have caused the annually required contributions to soar."84 To Christie's credit, he established a blue ribbon commission to propose reforms to the state's retirement systems.85 Unfortunately, the reforms have not been enacted.

New Mexico

Susana Martinez, Republican; Legislature: Divided

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Susana Martinez scored above average on spending and taxes in this report. Her proposed budget increases have been modest, although the legislature has usually spent more. On taxes, Martinez has pursued reforms to make New Mexico more economically competitive. In 2012 she signed a bill reducing gross receipts taxes on inputs to construction and manufacturing. But her biggest tax policy success was in 2013, when she pushed through a cut to the corporate income tax rate from 7.6 to 5.9 percent, phased in over five years.

New York

Andrew Cuomo, Democrat; Legislature: Democratic

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2011

Governor Andrew Cuomo received a grade of B on the 2014 Cato report, and he repeats his B this time around for his impressive tax cutting.

In 2014 Cuomo signed into law a package of tax reforms for businesses. The package cut the corporate income tax rate from 7.1 percent to 6.5 percent, reduced the corporate tax rate on qualified manufacturers from 5.9 percent to zero, ended a separate bank tax system, ended a surcharge on utility customers, and reduced the property tax burden on manufacturers.86

In 2016 Cuomo approved substantial individual income tax cuts in a compromise with Senate Republicans. The cuts will be phased in between 2018 and 2025, at which time they are expected to be saving taxpayers about $4 billion annually. The cuts will reduce statutory income tax rates on taxpayers with incomes below $300,000 a year. The deal did not include tax hikes on high earners, which Democrats in the legislature were promoting.

However, New York's spending is rising briskly. The general fund budget increased more than 8 percent in 2016 and is expected to increase more than 5 percent in 2017.87 Spending has been buoyed by an inflow of cash from legal settlements that the state has extracted from financial institutions. In 2015 and 2016, the state received more than $8 billion in settlements from 20 major companies.88 Cuomo's plan is to spend the money — mainly on capital projects — rather than using it to pay down the state's debt load, which is projected to continue rising.89

North Carolina

Pat McCrory, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: A; Took Office: January 2013

Governor Pat McCrory came into office promising major tax reforms and he has delivered. In 2013 he signed legislation to replace individual income tax rates of 6.0, 7.0, and 7.75 percent with a single rate of 5.8 percent. That rate was then reduced to 5.75 percent. The reform also eliminated the personal exemption and expanded the standard deduction. The 2013 law also cut the corporate income tax rate from 6.9 to 4.0 percent today, with a scheduled fall to 3.0 percent in 2017. The estate tax was repealed, and the sales tax base was expanded to cover more services.

In 2015 McCrory approved a further cut in the individual income tax rate from 5.75 to 5.5 percent, combined with an increase in the standard deduction. The 2015 law partly offset the revenue loss from income tax reductions with a broadening of the sales tax base. In 2016 McCrory approved another increase in the standard deduction.

McCrory has a good record on spending. The general fund budget will be just 8 percent higher in 2017 than it was when he took office in 2013. North Carolina retains the highest ratings on its debt from all three major credit-rating agencies.

North Dakota

Jack Dalrymple, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: B; Took Office: December 2010

North Dakota's boom from energy production has turned into a bust, as the price of oil has plunged since 2014. The strong economy had created a government revenue gusher fueled by rising severance taxes on oil production. Governor Jack Dalrymple and the legislature increased state spending substantially during the boom years.

But now that the economy is stagnant and tax revenues are falling, North Dakota policymakers are retrenching. Dalrymple has ordered broad-based cuts, and one-time appropriations have fallen substantially in the current two-year budget compared to the last one. Also, during the boom years, policymakers transferred substantial revenues into budget reserve funds, and those funds are now helping the state weather the downturn.

Dalrymple has signed into law numerous tax cuts. In 2013 he cut the top individual income tax rate from 3.99 to 3.22 percent and the top corporate tax rate from 5.15 to 4.53 percent. In 2015 he cut the individual rate further to 2.9 percent and the corporate rate to 4.31 percent. Despite the large budget gap this year, Dalrymple has resisted the urge to raise taxes.

Ohio

John Kasich, Republican; Legislature: Republican

Grade: B; Took Office: January 2011

John Kasich has been one of the best tax-cutting governors of recent years. In 2013 he approved a plan that cut individual income tax rates by 10 percent, with the top rate falling from 5.93 to 5.33 percent. The plan also exempted a portion of small business income from taxation. To partly offset the revenue loss, the plan broadened the sales tax base and raised the sales tax rate from 5.5 to 5.75 percent. In 2014 the income tax rate reductions were accelerated and personal exemptions were increased.

In 2015 Kasich signed further income tax rate cuts into law. Individual rates were slashed across the board, with the top rate dropping to 5.0 percent. The 2015 legislation also expanded the small business exemption. Taxpayers can now exempt the first $250,000 of business income, with business income over that amount taxed at just 3 percent.

The revenue losses from the 2015 tax cuts were partly offset by a cigarette tax increase from $1.25 to $1.60 per pack. In his 2016 State of the State address, Kasich promised further tax reforms next year.