Brazil is in the midst of one of the biggest corruption scandals in history. In the last three years, hundreds of businesspeople and politicians — including former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva — have been investigated and prosecuted for taking part in a massive bribery scheme involving state-owned companies. Although graft and influence peddling are not a new phenomenon in Brazil, bringing powerful individuals to justice certainly is.

Several reforms explain this transition to a more robust legal system. These include the introduction of plea bargaining in organized crime investigations; the creation of two public institutions to oversee the judiciary and the Public Ministry (the country’s top prosecutorial body), respectively; a competitive selection process based on merit for prosecutors and judges; and greater autonomy for the Federal Public Ministry and the Federal Police. A merit-based selection system for judicial appointments introduced in the 1988 constitution and greater access to public office by individuals with no previous political connections have also played a significant role in strengthening the country’s judicial institutions.

Brazil’s judiciary still has palpable problems, particularly its excessive cost and a bloated workload. In addition, judges enjoy certain prerogatives that are frequently abused. However, despite these shortcomings, the effectiveness of the judicial system has improved enormously since the 1990s, especially in fighting corruption.

Brazil’s recent experience holds lessons for other countries, especially in Latin America, where corruption, abuse of power, and impunity have been endemic features of public life.

INTRODUCTION

Do politicians get away with murder? In Brazil, they once did. In December 1963, Arnon de Mello — father of former president Fernando Collor de Mello — murdered a colleague on the floor of the Brazilian Senate.1 He was arrested, tried, found not guilty, and immediately released. Fifty years later, things have changed. Brazil’s Federal Police (PF) arrested the leader of the governing party’s bloc in the Senate, Sen. Delcidio do Amaral, after charging him with obstruction of justice.2 This was not an isolated case. Former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva (known as Lula), who is still one of the most powerful people in Brazil, was sentenced to almost 10 years in prison for money laundering.3 What changed?

In recent years, Brazil has transitioned to a more robust judiciary system dedicated to fighting corruption. The Federal Police, the Federal Public Ministry (MPF), and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (which is a separate division that handles cases with jurisdiction before the Supreme Court) have also transformed themselves into more effective institutions that promote equality before the law and prosecute powerful individuals when warranted.

This phenomenon is largely a product of Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash), an ongoing criminal investigation into institutionalized corruption. Launched in 2014, it has looked into wrongdoing by prominent politicians, businessmen, and state-controlled companies. The corruption brought to light by the investigation has received worldwide attention. The Associated Press called it “the biggest corruption scandal in the country’s history,”4 while Transparency International named it one of the most symbolic corruption cases in history.5

The operation started as an investigation of a small car wash gas station in the country’s capital. That investigation eventually led to the discovery of a huge network of bribery and corruption that involved many political actors of the ruling class in Brazil. From former presidents (such as Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Lula da Silva, and Dilma Rousseff) to leaders of the opposition and ruling parties in Congress (including the speaker of the House of Deputies and the president of the Senate), party chairmen, and even high court judges, the systemic web of corruption took Brazil into a frenzy of scandals that have come to light and are now under investigation and prosecution. Despite a history of negligence and overlooking criminal activities committed by politicians, the Brazilian legal system is now bringing people with money and political power to justice.

Operation Car Wash discovered an enormous network of corruption among Brazil’s leading construction companies and state-owned enterprises, specifically Petrobras (the national oil corporation), the Brazilian National Development Bank, and Eletrobras (a major electric public utilities company). Investigators unlocked a scheme of bribery in exchange for contracts that resulted in kickbacks ranging from 1 percent to 5 percent of every contract. So far, federal prosecutors are seeking to recover in court $12 billion from those implicated.6

The scandal gave rise to other investigations as well, such as the discovery of irregular campaign donations for leading candidates in Brazilian elections in the last few decades. The Superior Tribunal on Electoral Affairs of Brazil narrowly voted down a case that could have annulled the last presidential election and revoked the mandate of current president Michel Temer, on the grounds of undeclared donations to the campaign of impeached president Dilma Rousseff — who preceded Temer in office, and with whom Temer ran on the same ticket as her vice president. The runner-up in that race, Sen. Aecio Neves, is also implicated — allegedly having received money from the same companies that donated to Rousseff and Temer. All this has taken place while Brazil has suffered from its deepest economic crisis since the 1930s.

Six main factors made Operation Car Wash possible and successful:

- The plea bargain option;

- Merit-based selection for the judiciary introduced in the 1988 constitution;

- A strong system of incentives to choose qualified public servants;

- The 45th amendment to the constitution and the creation of the National Council of Justice and the National Council of the Public Ministry;

- Qualified Supreme Court appointments; and

- The autonomy of the Federal Police and Federal Public Ministry.

Those changes in the legal system in recent years have increasingly affected the incentives and behavior of both individuals and institutions.

FACTOR 1: THE PLEA BARGAIN OPTION

Although plea bargaining is a common courtroom practice in common law jurisdictions, it is rare in countries with civil law systems, in which judges play a greater role in the conduct, discovery, instruction, and deliberation stages of a trial.7 Until recently, the idea that the prosecution and the defense could sit and negotiate a sentencing deal was unheard of in Brazil.8 Today, the country has a more modest version of the plea bargain, called delação premiada — which literally translates to “awarded delation.”

Plea bargaining was first introduced into Brazil’s legal system in 1990 as a reaction to a series of heinous crimes, including rape, kidnapping, and murder.9 Numerous pieces of legislation in 1995,10 1998,11 2006,12 and 201113 expanded its reach. Most important, in 2013, the Congress passed the “Law against Organized Crime,” which outlines the procedure and criteria for its application. The act defined “organized crime” as criminal acts committed by four or more people. To make enforcement possible, the act established a results-based system of incentives to encourage people to provide information that can lead to the conviction of other criminal suspects.

For a plea deal to be valid, the information provided by the defendant must achieve one of the following: identify the other participants of the criminal organization and criminal offenses committed by them, disclose the hierarchical structure and division of tasks within the criminal organization, prevent criminal offenses arising from the activities of the criminal organization, recover total or partial gains from offenses committed by the criminal organization, and find the victim with his or her physical safety preserved.14

This set of requirements is designed to increase the system’s effectiveness. The benefits of collaboration to a defendant include the possibility of reducing a prison sentence by up to two-thirds, replacing the sentence with a deprivation of civil rights, or even having a pardon promptly granted if the collaboration is considered to be of major importance.15

Most, if not all, collaborations include disclosure of evidence, because witness accounts are not sufficient for a conviction.16 Evidence is required because individual testimony in Brazil is regarded as highly unreliable.17 Defendants and victims are not even required to testify truthfully before a judge, and other witnesses’ testimony is often deemed unreliable, so judges tend not to convict someone purely on the basis of witness testimony. Compared with the U.S. legal system, which emphasizes cross-examination and imposes penalties for perjury, Brazil’s system incentivizes testimonial falsehoods, which makes oral testimony unreliable.

Plea bargaining has helped transform the incentives for presenting testimony. Before plea bargaining was introduced, defendants could easily lie or obfuscate the truth because they faced no negative repercussions for doing so. Now, there are incentives not only to be truthful at trial, but also to effectively collaborate during the investigation phase, when evidence is gathered and presented before a judge. This change is the biggest in the system, and it made Operation Car Wash possible. Without plea bargains, many of the investigations undertaken during the operation would simply not have occurred. As of May 2017, 155 such agreements had reached a settlement.18

For example, a plea deal by former Petrobras director Paulo Roberto Costa revealed important information about the methods of a criminal operation.19 It also provided evidence that connected politicians to the scheme.20 As a result, Sen. Delcídio do Amaral was arrested after attempting to obstruct an investigation.21 However, the senator himself agreed to a plea deal: he provided information linking President Rousseff and former president Lula to corruption that resulted in legal charges.22

Operation Car Wash could never have gotten as far as it did without the incentives established by the system of plea bargaining.23 Most of the major scandals that have recently rocked Brazil were uncovered thanks to these agreements.

The plea bargain option represents an important step toward creating a more resourceful and time-efficient judiciary. It also presents a real prospect of improving a severely overloaded justice system. According to recent estimates, there are currently two pending lawsuits for each Brazilian24 — a major bottleneck that hinders the timeliness and effectiveness of judiciary.25 Additionally, the Federal Public Ministry estimates that Brazil recovered $225 million in corruption cases through collaboration agreements.26

The system of plea bargaining transformed the incentive structure within Brazil’s judicial system by influencing the actions of defendants during criminal lawsuits. Prior to the implementation of this instrument, defendants faced incentives not only to suppress relevant information, but also to obstruct justice. Today, incentives effectively encourage collaboration with the justice system, prevent impunity, and bring criminal suspects to trial regardless of social status.

FACTOR 2: A MERIT-BASED SELECTION SYSTEM AND GREATER ACCESS TO PUBLIC OFFICE

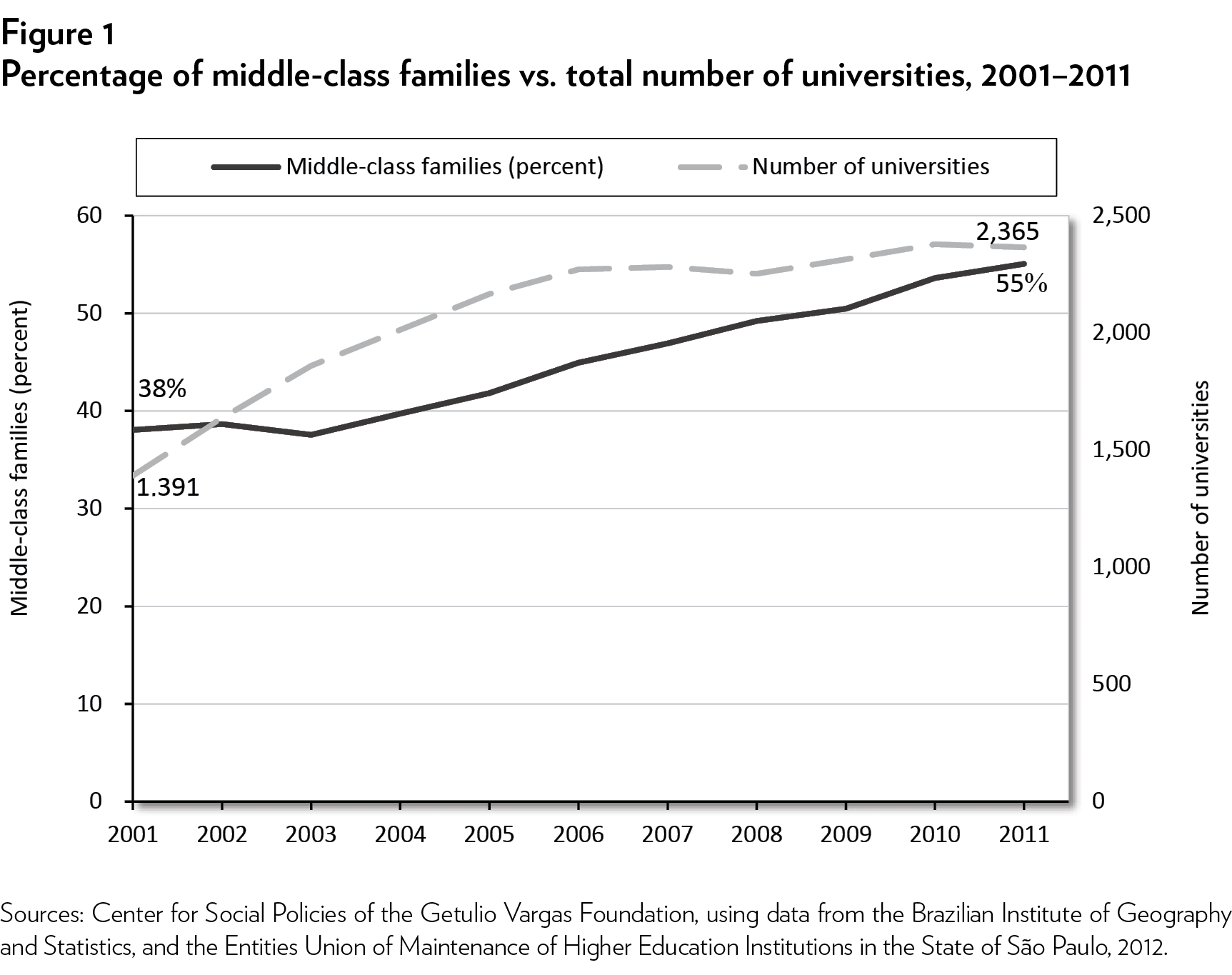

Historically, the exercise of power in Brazil has been associated with a traditional political establishment that was long considered to be out of touch with the majority of the people.27 However, new criteria set by the 1988 constitution significantly reduced reliance on political connections to gain access to public office in the judiciary. These changes were bolstered by the growing number of people pursuing careers in the legal profession, which in turn is a result of Brazil’s economic transformation since the early 1990s. The demographic group that has benefited the most from these developments is the middle class, which has expanded significantly in the past two decades, becoming the largest segment of the population in 2009.28 The middle class has grown from comprising approximately a third of the population to the majority — from 63 million people in 2005 to 103 million in 2011, which represents 55 percent of families in Brazil.

The growth of the middle class also increased the number of students attending university. With more people now able to afford a higher level of education, there are more students and hence more law students. As the middle class grows, so do higher education and the legal profession (see Figure 1).

After passing the bar exam, the path to becoming a judge or prosecutor begins with a mandatory three years of practicing law.29 After that, there are two distinct ways to obtain a permanent judicial post. The more common path, through which 80 percent of judges are chosen, involves a rigorous process of open, public, and objective selection. This method gives greater opportunities to members of the middle class with no previous political connections.

The other path, known as o quinto — which literally translates as “the fifth” because 20 percent of judges for higher courts are selected this way — can be heavily influenced by political connections.

This selection process is outlined in a constitutional clause, which instructs the Order of Attorneys of Brazil (the Brazilian bar association) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to each create a list with six nominees and submit it to the court with a vacant judicial seat.30 The court then creates a new list with three nominees drawn from the previous lists. The court’s list is then sent to the chief of the respective executive office — for instance, the governor for state judges — who will choose someone from that list to fill the position. Nominees on each list need major support from the institutions that put their names forward. In the last phase, when the chief of the executive office makes a choice, political influence plays an even stronger role. Hence, to earn this promotion, candidates must face tough political competition within the institution to which they belong and wield enough influence to be selected by the relevant executive officer.

However, since a greater number of candidates come from the first path, that process has significantly altered the Brazilian judicial system because it facilitates the hiring of judges and prosecutors who do not have strong political backgrounds. Moreover, the public selection process incorporates a system of incentives outlined by the Brazilian constitution.31 The process follows several constitutional principles of administrative law, including impartiality and equality.32

The prerequisites for the selection process are a law degree, passing the Brazilian bar exam followed by at least three years of practice, Brazilian citizenship, compliance with military and electoral obligations, and no criminal record. The process itself is set forth by public notice and is divided into a five-step process of elimination.33 The first two steps are tests used to evaluate a broad range of legal knowledge. The third step evaluates the candidate’s mental and physical condition and medical records. The fourth step is an oral exam. The fifth and final step consists of a point-scoring system based on credentials, publications, and other qualifications of the candidate. The procedure explicitly disregards the candidate’s political background and focuses instead on practical qualifications. Additionally, the system establishes different merit goals as incentives throughout that person’s career.

An approved candidate will be offered a position as a substitute judge in a small county, with the possibility of advancing to intermediate-sized counties and then, potentially, larger-sized counties. Ultimately, the judge may become a Justice of Appeal, known as a desembargador. (Supreme Court judges are selected according to different criteria, as explained later.)

The merit-based selection system established in the 1988 constitution has increasingly allowed ordinary people without political influence to reach top positions in the Brazilian judiciary. Once in office, the individuals selected can exercise their duties without fear or favor.

One relevant figure selected in this way is the young federal judge Sergio Moro, who is the leading face of Operation Car Wash. Only 45 years old, Moro has handled most of the initial cases that have resulted from this operation (that is, before the appeals process). The media usually describe him as tough, rigorous,

and technical.

FACTOR 3: A STRONG SYSTEM OF INCENTIVES TO CHOOSE QUALIFIED PUBLIC SERVANTS

The incentives to select well-qualified public servants, specifically those in powerful decisionmaking positions such as judges and prosecutors, have become more robust in the past two decades. This has both positive and negative impacts on many people’s decisions to pursue a career in public service.

A Highly Competitive Career Path

According to a report by the Brazilian bar association, Brazil has more law schools — more than 1,400 — than the rest of the world combined.34 The country has over 900,000 lawyers — and many more law graduates — often competing for top legal positions.35 The supply of candidates to become judges and prosecutors remains high because public law remains a very attractive career option for high school graduates. Nonetheless, increased law school enrollment does not necessarily create more lawyers. Over the past decade, the percentage of law graduates who passed the bar exam has fluctuated between 10 percent36 and 25 percent.37

The typical career goal for members of this large demographic is to be a judge or a prosecutor. Both professions have a legal right to the same salaries: an entry-level prosecutor must be paid the same as an entry-level judge. With 100 to 250 candidates seeking a single position, competition is stiff.38

Public Law Careers: High Salaries, Tenures, and Honors

Public law jobs are among the highest paid in Brazil. A judge, by the start of his or her career, earns a base annual salary of about $76,160. Compared with the average annual income in Brazil of around $7,200, this is a significant sum.39 The income of Brazilian judges is further increased by bonuses and various other perks, with total compensation sometimes reaching up to $226,000 a year.40 Unfortunately, bonuses are often awarded for dubious reasons. For example, judges receive around $13,200 a year for housing assistance, even though they already have among the highest salaries in the country.41

Tenure is another important benefit. After a probationary term of two years, tenure makes it extremely difficult to fire judges, a system which guarantees them stability and increasing salaries for most of their lives.

Negative Impacts

Tenure also generates bad incentives because it allows judges to behave improperly with impunity. Only in the most severe cases are tenured judges forced into compulsory retirement — with full pay for life. For instance, in the north of Brazil, a judge was caught sexually assaulting his female assistants in their workplace.42 As a result, he was forced to retire but will receive full payment of his salary for the rest of his life. Even at the end of his life, his payment will not stop: If his wife survives him, she will receive the money until her own death.

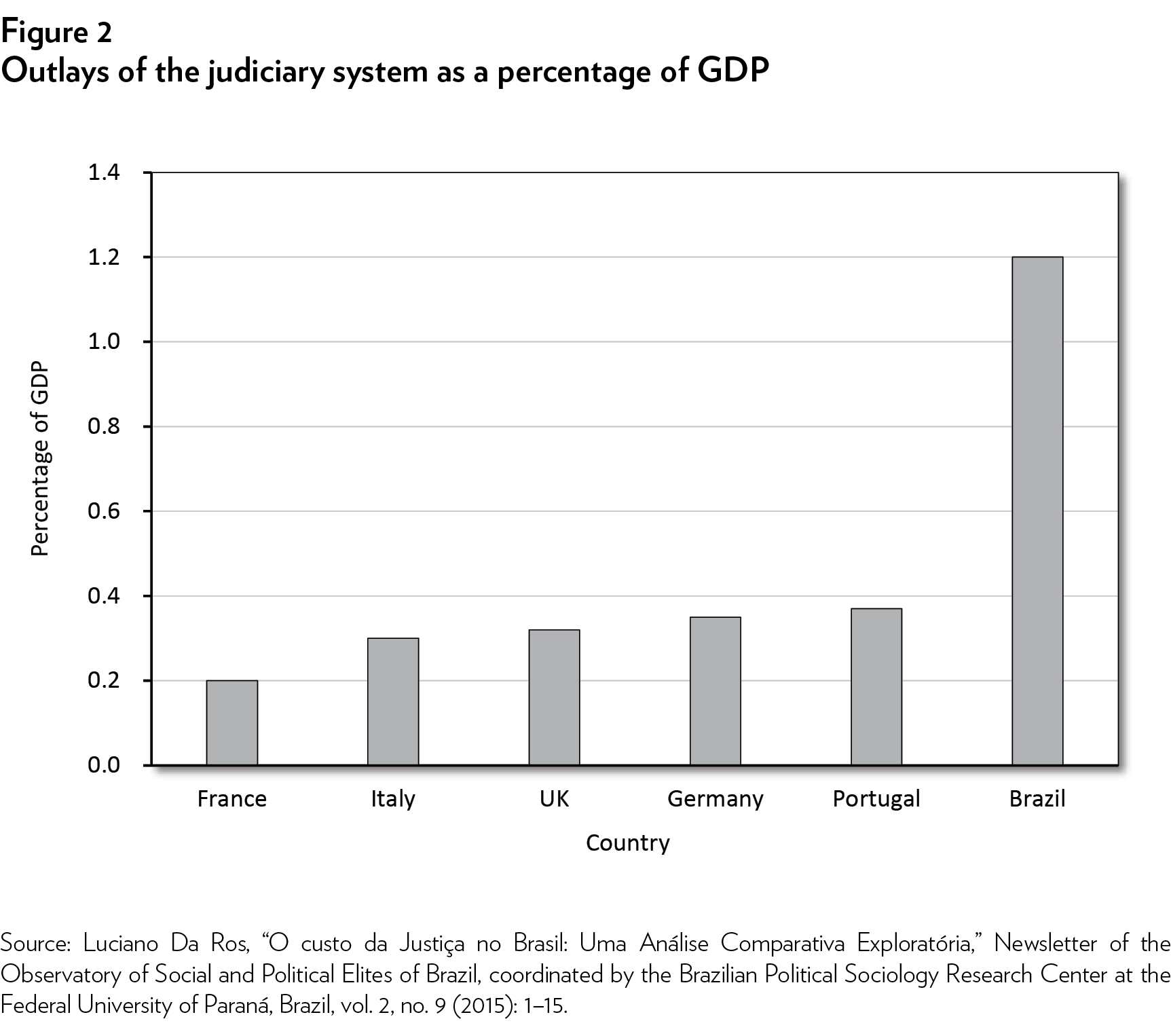

Given the high salaries and bonuses paid to judges and prosecutors, Brazil’s judiciary is very expensive. In 2014, the National Council of Justice estimated that the entire Brazilian judiciary cost approximately $30 billion, equivalent to 1.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).43 Personnel expenses represent 89.5 percent of the total cost.44 Western European countries such as France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and the United Kingdom spend no more than 0.4 percent of GDP on their respective justice systems (see Figure 2).45 The figure for the United States is approximately 0.13 percent of GDP.

Another bad incentive concerns fiscal policy, because Brazil’s judiciary is responsible for its own budget.46 The federal Supreme Court (STF) approves its own budget, and the presidents of state tribunals vote on state courts’ budgets. Thus, the judiciary may increase its budget if it considers it necessary, and the legislature merely ratifies it.47

Although very expensive and not always effective, Brazil’s newly improved judiciary still makes for an attractive career option, regardless of political connections.

FACTOR 4: THE 45TH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION AND INSTITUTIONAL OVERSIGHT

In 2004, the Brazilian Congress approved the 45th amendment to the 1988 constitution, which came to be known as the “Judicial Reform.”48 The amendment brought a series of changes to the judiciary’s functions, including stricter requirements on hearings before the Supreme Court, measures to turn the Court’s decisions into precedent (unusual in a civil law system), and the creation of two institutions charged with oversight: the National Council of Justice (CNJ) and the National Council of the Public Ministry (CNMP).

The CNJ’s mission is to protect the autonomy of the judiciary. Its goal is to enhance the effectiveness of the Brazilian judicial system, primarily through improved supervision, administrative controls, and transparency. To that end, it enforces the Statute of the Magistrates, a code of rules that sets duties and rights for every Brazilian judge, oversees the functioning of the judicial system, hears complaints, establishes disciplinary proceedings, and promotes measures to increase courts’ effectiveness.49 The CNMP is tasked with administrative, financial, and disciplinary supervision of the Public Ministry (MP), the country’s top prosecutorial body. The MP is divided between the Federal Public Ministry (MPF) and the state Public Ministries. Specifically, the CNMP has the authority to review the legality of MP staff actions, make administrative decisions, respond to complaints against MP staff, review disciplinary proceedings, and develop an annual report on the status of the MP.50

Both the CNJ and CNMP have strengthened the judiciary by incentivizing greater effectiveness, rigorously supervising the judiciary, and implementing independent oversight to combat internal corruption. The CNJ also publishes comprehensive reports on the efficiency of the judiciary, such as the Justice in Numbers Report, and sets goals for state courts, such as general timelines and quantitative deliverables for measuring effectiveness.51

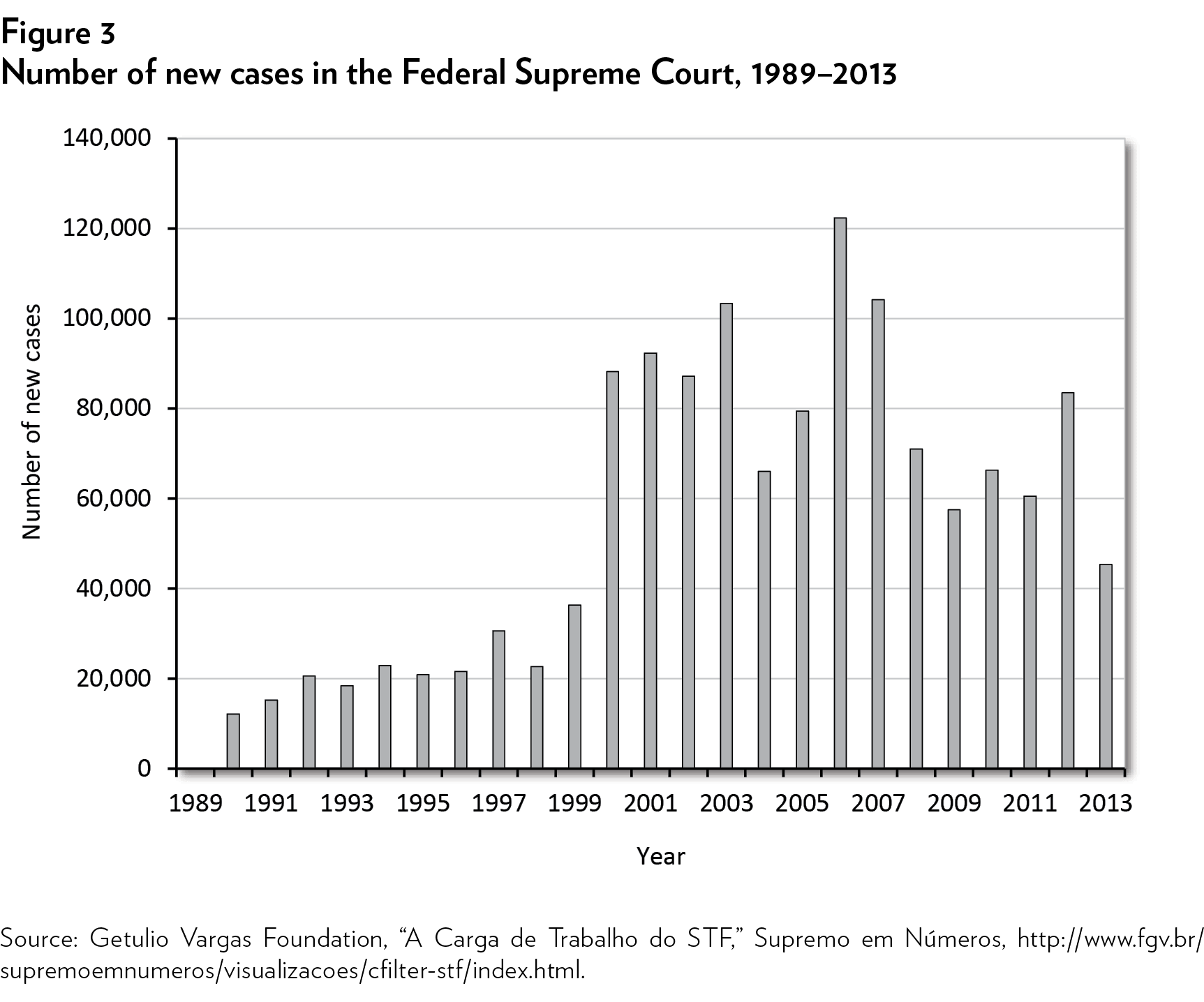

The CNJ has substantially helped the judiciary become more expeditious in its decisionmaking. For instance, the Brazilian Supreme Court is one of the busiest courts in the world, with as many as 100,000 new cases per year.52 However, the number of pending cases began to drop after the 45th amendment was ratified in 2006 (see Figure 3).53

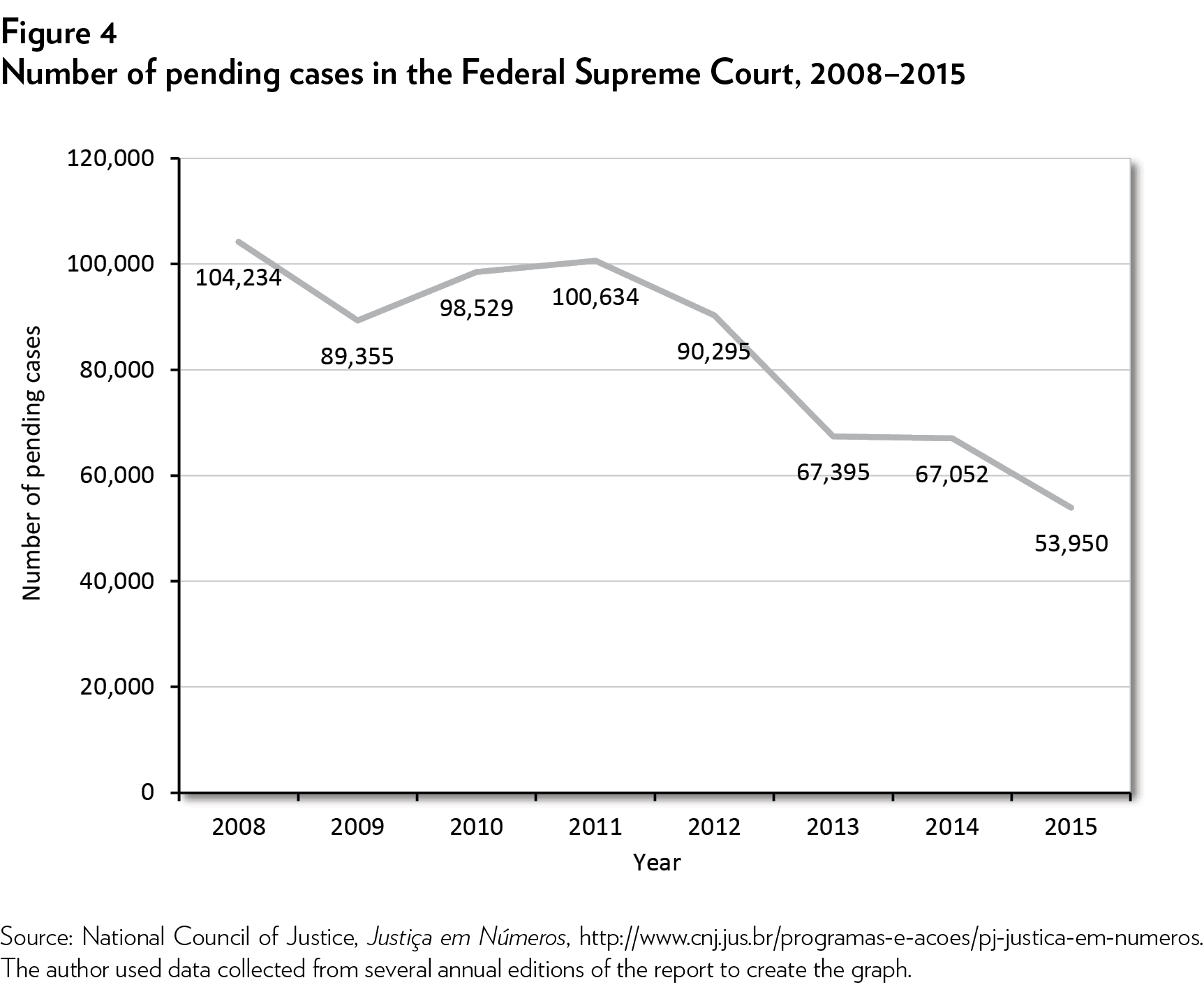

The initial sharp rise in litigation is partly due to the 1988 constitution, which empowered ordinary Brazilians to defend their rights before the judiciary. As a result, an overwhelming number of new cases reached the Supreme Court. While Brazil’s population grew by 30 percent over the ensuing 25 years, the number of cases grew by 27,000 percent during the same period.54 Although the number of cases is still high, the 45th amendment is widely credited with helping to significantly reduce the number of Supreme Court cases, as it made settlement before reaching the STF more likely.55 The number of cases before the STF with decisions pending continues to fall, reaching its lowest number in a decade in 2015, with only 53,950 cases undecided (see Figure 4).56

However, the CNJ’s corruption oversight remains weak. While it has become more effective, it still has a long way to go. Since its founding, the CNJ has filed 7,200 disciplinary complaints but resolved only 78.57 Worse, disciplining members of the judiciary remains extremely difficult, because the CNJ still maintains a close relationship with judges and remains hesitant to charge them. For example, Justice Nancy Andrighi, the head of the CNJ, has been criticized by her colleagues for a speech in which she came out strongly against nepotism and for opening an investigation of a fellow judge over charges of corruption.58 In another case, a small-county judge took two arbitrary measures — regarding the disruption of the WhatsApp mobile messaging app in Brazil and the arrest of Facebook’s vice president for Latin America — before the CNJ started investigating him.59

FACTOR 5: QUALIFIED SUPREME COURT APPOINTMENTS

The Brazilian Supreme Court is composed of 11 justices appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, in a process similar to that in the United States. The chief justice is selected by a vote by his or her colleagues for a term of two years. Unlike the judicial systems of many of its neighbors in South America, the appointment process has enabled the Brazilian Supreme Court to retain ideological stability throughout the past couple of decades, enforcing checks and balances instead of being subjected to changes in the political winds depending on which party is in power.

It is important to note that the Brazilian Workers’ Party, which held power from 2003 to 2016, has longstanding alliances with other Latin American left-wing parties. This ideological alignment proved advantageous when several of those allied parties held power around the same time, most notably Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, Nestor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernandez in Argentina, and Evo Morales in Bolivia. However, in those countries, violations of the rule of law became commonplace. In contrast, Brazil’s democratic institutions have proven remarkably resilient, even after Workers’ Party governments appointed nine justices to the Supreme Court. Of these nine justices, eight have extensive and accomplished legal careers (the exception being Justice Dias Toffoli, a former election lawyer for the Workers’ Party60 who had previously failed a judicial selection61).

The Supreme Court’s independence was evident in the 2005 corruption scandal known as the Mensalão, which translates roughly as “big monthly payment.”62 Despite special judicial privileges granted to senior public officials by the constitution, the STF convicted top political figures on corruption charges, including some with close links to former president Lula da Silva. Notably, the Workers’ Party had appointed many of the justices.63 The Court’s independence was also evident in the denial of several requests made by President Rousseff, Lula da Silva’s successor, to stop impeachment proceedings against her.64 Despite her protests, the process moved along and Rousseff was impeached in April 2016.65

It is worth noting that the STF is constitutionally protected against any interference from the executive or the legislature. For instance, the Supreme Court could nullify a constitutional amendment that alters its independence or prerogatives. Unlike many neighboring countries, Brazil has maintained a strong separation of powers between the judiciary and the other branches of government. Every administration following the 1988 constitution has respected that separation.

FACTOR 6: AUTONOMY OF THE FEDERAL POLICE AND FEDERAL PUBLIC MINISTRY

The autonomy and independence of the Federal Public Ministry is a recent accomplishment. The Public Ministry officially gained autonomy from the executive branch following implementation of the 1988 constitution — an important step for a country with a history of abusive behavior by the executive. Nonetheless, through the 1990s, Brazilian prosecutors general routinely refused to bring charges against senior officials of the executive branch. Today, by contrast, the MPF has earned praise for the significant degree of independence it has achieved.66 Although the president enjoys full discretion in appointing the prosecutor general, for more than a decade the president chose — from the list submitted by all federal prosecutors — the candidate who received the most votes from colleagues.67

The prosecutor general recently stated that laws against corruption and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions are the main factors behind the criminal investigations and indictments made by MPF.68 The convention sets standards and procedures to combat systemic bribery, especially in developing countries such as Brazil. In the same interview, the prosecutor general publicly responded to Lula da Silva’s complaint of ingratitude, stating that he owes nothing to the executive, thereby signaling the MPF’s independence.69

In October 2014, the Federal Police also gained greater independence from the Ministry of Justice, via executive order no. 657, informally known as the MP da Autonomia (Provisional Measure of Autonomy). This measure requires that the PF director must have served previously as a federal police officer, thus giving the institution greater independence to choose its own leadership.70 Police officers lobbied the presidency hard for this change.71

Investigation methods have also improved greatly. The MPF and PF have had several joint task forces throughout Brazil carrying out important investigations as part of Operation Car Wash, after the director of the PF said his agency would not lag behind the MPF in investigating the scandal.72 Those task forces have focused on coordinated crimes that could be linked together. The MPF and PF’s work has brought them international recognition and greater prestige.73

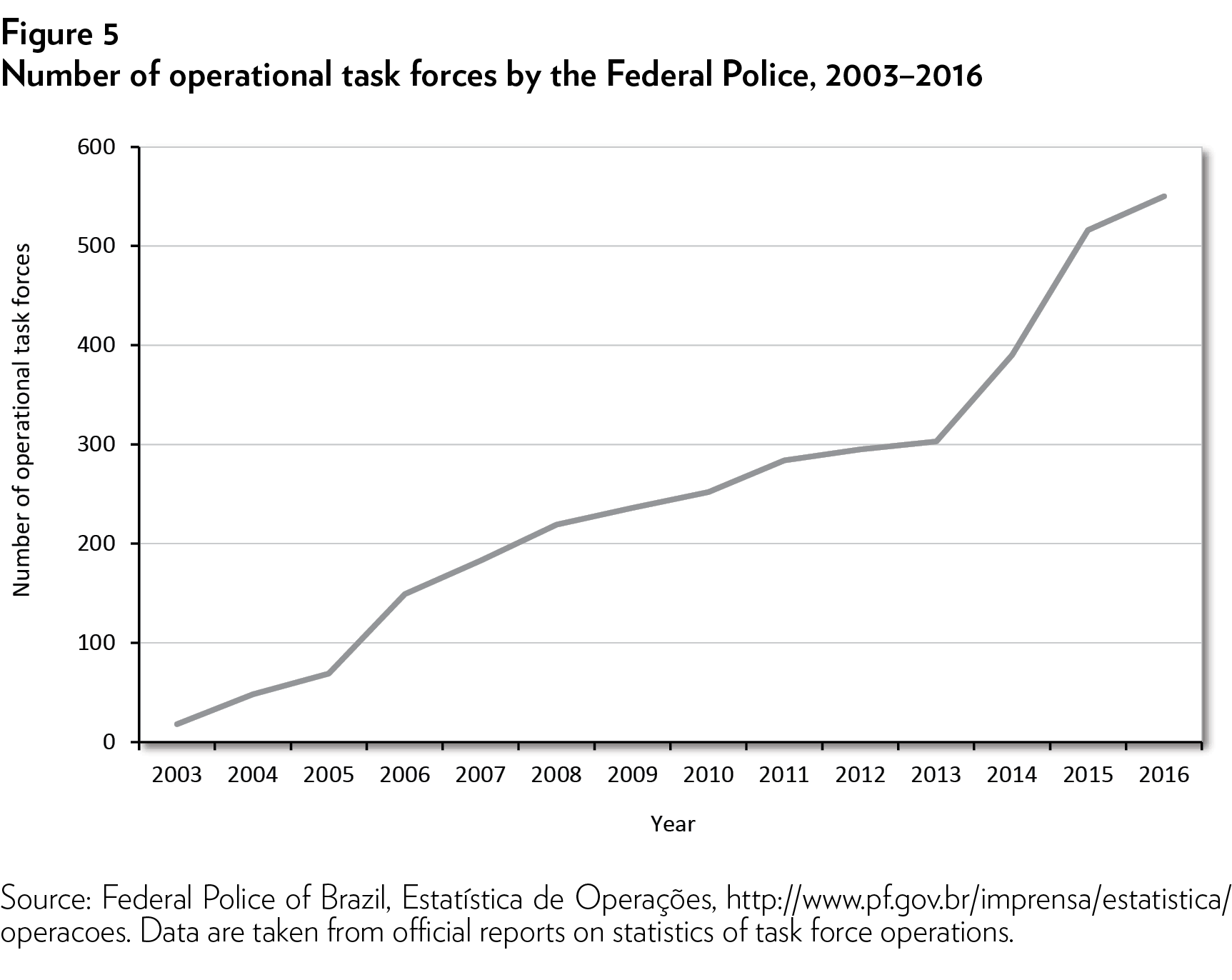

By dedicating people and resources to investigating related crimes instead of investigating them separately, the PF and the MPF were able to better focus their efforts and better utilize their personnel with the experience and technical expertise needed to go after criminal organizations. Although common in other countries, this type of investigation management is another recent development in Brazil, starting with 18 task forces in 2003 and growing to 550 by 2016 (see Figure 5).74

The management of resources has improved substantially, as the results achieved by the PF and MPF have bolstered the image and prestige of both institutions. The success of the task forces has provided an incentive for their operating procedure to become standard for corruption investigations.75

CONCLUSION

The judiciary in Brazil is far from perfect, but its effectiveness has improved enormously since the early 1990s. The legal, social, and institutional changes reviewed in this paper show how creating the right set of incentives can strengthen the judiciary of an emerging country, even one with a history of corruption and of politicians used to acting with impunity.

Brazil has developed a strong system of incentives to select qualified people who are able and willing to confront the political and business establishment, including in some of the biggest corruption cases in the country’s history. Other countries could learn from Brazil’s much improved process for selecting good judges and prosecutors, while avoiding some of the mistakes the country still needs to correct in the future.

NOTES

This paper was originally submitted for publication on April 1, 2017.

- “Arnon de Mello, Senator profile,” Senado da República, http://www25.senado.leg.br/web/senadores/senador/-/perfil/1479.

- “Injunction no. 4039,” Supremo Tribunal Federal, November 25, 2015, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/noticiaNoticiaStf/anexo/Acao_Cautelar_4039.pdf. As explained later in this paper, Sen. do Amaral entered a plea deal that exempted him from further prosecution in the case in which he was involved.

- Ernesto Londoño, “Ex-President of Brazil Sentenced to Nearly 10 Years in Prison for Corruption,” New York Times, July 12, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/12/world/americas/brazil-lula-da-silva-corruption.html.

- “Politicians Face Investigation in Brazil’s Biggest Ever Corruption Scandal,” Associated Press/Guardian, March 7, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/07/brazilian-court-approves-investigation-into-politicians-in-petrobras-scandal.

- “Transparency International to Pursue Social Sanctions on 9 Grand Corruption Cases,” Trans-parency International, February 10, 2016,

http://www.transparency.org/news/pressrelease/transparency_international_to_pursue_social_sanctions_on_9_grand_corruption. - “A Lava Jato em Números,” Ministério Público Federal da República Federativa do Brasil, http://lavajato.mpf.mp.br/atuacao-na-1a-instancia/resultados/a-lava-jato-em-numeros.

- Antoine Garapon and Ioannis Papapoulos, Julgar Nos Estados Unidos E Na França (Rio de

Janeiro: Lumen Juris, 2008). - It is important to note that plea bargaining does not fully exist in Brazil. It was proposed in the project for a new penal code in 2012, but a special commission excluded it, saying “it was not the moment yet.” “Projeto de Lei do Senado no. 236,” Special Commission for the New Penal Code, December 17, 2013, http://www.senado.leg.br/atividade/rotinas/materia/getPDF.asp?t=143412&tp=1.

- “Act no. 8072,” Presidência da República, July 25, 1990, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8072.htm.

- For accounting crimes, such as tax fraud and tax evasion, and crimes committed by a professional criminal organization.

- “Act no. 9613,” Presidência da República, March 3, 1998, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9613.htm.

- “Lei de Drogas Act no. 11343,” Presidência da República, August 23, 2006, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11343.htm.

- “Act no. 12.529,” Presidência da República, November 30, 2011, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/Lei/L12529.htm.

- Translated from the following: I - a identificação dos demais coautores e partícipes da organização criminosa e das infrações penais por eles praticadas; II - a revelação da estrutura hierárquica e da divisão de tarefas da organização criminosa; III - a prevenção de infrações penais decorrentes das atividades da organização criminosa; IV - a recuperação total ou parcial do produto ou do proveito das infrações penais praticadas pela organização criminosa; V - a localização de eventual vítima com a sua integridade física preservada. “Act no. 12.850,” Presidência da República, August 2, 2013, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2013/lei/l12850.htm.

- Ibid.

- Someone cannot be found guilty solely on oral evidence obtained through a plea deal. Other evidence must be presented for a defendant to receive a guilty verdict by a judge.

- See Bruno Cruz da Silva vs Ministério Público do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, 70068866466/CNJ: 0096840-09.2016.8.21.7000 (2016).

- “A Lava Jato em Números.”

- “Termo de Colaboração no. 1,” Polícia Federal 2014, http://media.folha.uol.com.br/poder/ 2015/03/11/termo-de-colaboracao-001.pdf.

- “Termo de Colaboração no. 11/12,” http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/fausto-macedo/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2016/01/dep-cervero-t.pdf.

- “Açao Cautelar 4039,” Supremo Tribunal Federal, November 25, 2015, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/noticiaNoticiaStf/anexo/Acao_Cautelar_4039.pdf.

- “Procedimiento Oculto e em Segredo de Justiça, PET 5952,” Ministério Público Federal, February 22, 2016, http://veja.abril.com.br/complemento/brasil/pdf/delacao-delcidio.pdf.

- “Colaboração premiada,” MPF Combate à Corrupção, http://lavajato.mpf.mp.br/atuacao-na-1a-instancia/investigacao/colaboracao-premiada.

- Maria Tereza Sadek, “Acesso à Justiça: um direito e seus obstáculos,” Revista USP 101 (2014): 55–66, http://www.revistas.usp.br/revusp/article/download/87814/90736.

- Conselho Nacional de Justiça, “Dados Estatísticos,” http://www.cnj.jus.br/programas-e-acoes/politica-nacional-de-priorizacao-do-1-grau-de-jurisdicao/dados-estatisticos-priorizacao; and Conselho Nacional de Justiça, “Justiça em Números,” http://www.cnj.jus.br/relatorio-justica-em-numeros/#p=justicaemnumeros.

- Deltan Dallagnol, “As luzes da delação premiada,” Época, July 4, 2015, http://epoca.globo.com/tempo/noticia/2015/07/luzes-da-delacao-premiada.html.

- Bruno Garschagen, Pare de Acreditar no Governo (Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2015).

- Statistics are from the Center for Social Policies of Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV), obtained by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, http://www.cps.fgv.br/cps/pesquisas/Politicas_sociais_alunos/2012/Site/11_1BES_Nova%20Classe_Media.pdf.

- “Resolução no. 1079/2015-COMAG,” Diário de Justiça do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, 2015, http://www.jusbrasil.com.br/diarios/DJRS/ 2015/06/08.

- Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, Article 94.

- Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, Article 37, sec. 2, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/ConstituicaoCompilado.htm.

- Supreme Court ruling: ADI 498, Rel. Min. Carlos Velloso (DJ de 9-8-1996) e ADI 208, Rel. Min. Moreira Alves (DJ de 19-12-2002).

- “Resolução no. 1079/2015-COMAG,” Diário de Justiça do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, 2015, http://www.jusbrasil.com.br/diarios/DJRS/ 2015/06/08.

- “Brasil, sozinho, tem mais faculdades de Direito que todos os países,” Order of Attorneys of Brazil (OAB), October 14, 2010, http://www.oab.org.br/noticia/20734/brasil-sozinho-tem-mais-faculdades-de-direito-que-todos-os-paises.

- OAB, “Quadro de Advogados,” http://www.oab.org.br/institucionalconselhofederal/quadroadvogados.

- “Exame de Ordem em Números,” 2014, http://fgvprojetos.fgv.br/sites/fgvprojetos.fgv.br/files/relatorio_2_edicao_final.pdf.

- OAB, “Desempenho no Exame de Ordem,” October 2014, http://www.oab.org.br/content/pdf/examedeordem/exame_de_ordem_desempenho_ies_campus.pdf.

- Tribunal de Justiça do Rio Grande do Sul, “Concurso de Juiz de Direito Substituto tem cerca de 100 candidatos por vaga,” February 20, 2009, http://tj-rs.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/833447/concurso-de-juiz-de-direito-substituto-tem-cerca-de-100-candidatos-por-vaga. Four thousand

candidates competed for 16 places. Tribunal

Regional Federal da 4ª Região, “Concurso Público

Sevidores,” 2017, http://www2.trf4.jus.br/trf4/controlador.php?acao=pagina_visualizar&id_pagina=125. - Wage data obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Trading Economics, “Brazil Real Average Monthly Income,” http://www.tradingeconomics.com/brazil/wages.

- Simon Romero, “Brazil, Where a Judge Made $361,500 in a Month, Fumes over Pay,” New York Times, February 10, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/11/world/americas/brazil-seethes-over-public-officials-super-salaries.html?_r=0.

- National Council of Justice (CNJ), Resolution 199, 2014, http://www.cnj.jus.br/images/imprensa/Resolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o_n__199-GP-2014.pdf.

- “Juiz do AM acusado de pedofilia pede aposentadoria,” Revista Consultor Jurídico, July 12, 2009, http://www.conjur.com.br/2009-jul-12/juiz-trabalho-acusado-pedofilia-aposentadoria-tj-am.

- 2014 is the most recent official estimate

available. - National Council of Justice (CNJ), Justiça em Números, 2015.

- European Judicial Systems, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), https://public.tableau.com/views/2010-2012-2014Data/Tables?:embed=y&:display_count=yes&:toolbar=no&:showVizHome=no.

- Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, Article 99, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/ConstituicaoCompilado.htm.

- The finances of the judiciary must conform with the annual budget presented by the executive branch and passed by the Congress. However, due to political favors, the executive and the legislative branches tend to be “generous” with the judiciary.

- This amendment also greatly expanded the jurisdiction of the Brazilian Labor Justice, a separate branch of the judiciary. The expansion is not related to the thesis presented in this paper.

- Conselho Nacional de Justiça, http://www.cnj.jus.br/sobre-o-cnj/quem-somos-visitas-e-contatos.

- Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público “Apresentação,” June 20, 2017, http://www.cnmp.mp.br/portal/institucional/o-cnmp/apresentacao.

- CNJ, Justiça em Números, 2015, http://www.cnj.jus.br/relatorio-justica-em-numeros/ #p=justicaemnumeros.

- “When Less Is More,” The Economist, May 21, 2009, http://www.economist.com/node/13707663.

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Supremo em Números, http://www.fgv.br/supremoemnumeros/.

- CNJ, Justiça em Números, 2014, http://www.cnj.jus.br/relatorio-justica-em-numeros/ #p=justicaemnumeros.

- Brazil, 45th Amendment, December 30, 2014, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc45.htm. This amendment established institutes that increased the binding force of decisions by the tribunals over lower-level jurisdictions. MG/LF, Repercussão geral e súmulas vinculantes diminuem o número de processos no STF, STF’s newsletter, October 4, 2008, http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoticiaDetalhe.asp?idConteudo=97176&caixaBusca=N.

- The eleven-justice Supreme Court is able to rule on thousands of cases every year because of its internal division of labor. Each justice has his or her own cabinet, which includes “auxiliary judges.” These are usually judges from state and federal courts picked by a justice to serve temporarily as his or her clerks on the Supreme Court. The auxiliary judges decide most of the cases on the basis of previous votes and opinions of their respective justice. Moreover, each case is assigned to an individual justice, called the rapporteur, who summarizes the case, casts the first vote, and makes recommendations to the rest of the Court. The other justices can follow the rapporteur’s recommendation or give a different decision. In over 95 percent of the cases, a majority of the court agrees with the rapporteur’s recommendation. See Damares Medina, “Como funciona o STF,” Damares Medina Advocacia, November 16, 2015, http://damaresmedina.com.br/como-funciona-o-stf; and Lilian Venturini, “Quem são e o que fazem os juízes auxiliares do Supremo,” Nexo, January 27, 2017, https://www.nexojornal.com.br/expresso/2017/01/25/Quem-s%C3%A3o-e-o-que-fazem-os-ju%C3%ADzes-auxiliares-do-Supremo.

- Débora Zampier, “Reforma constitucional que criou CNJ completa 10 anos,” Agência CNJ de Notícias, December 22, 2014, http://www.cnj.jus.br/noticias/cnj/62361-reforma-constitucional-que-criou-cnj-completa-10-anos.

- Severino Motta, “Se eleição fosse hoje, Nancy não se elegeria presidente do STJ,” Radar Online, April 29, 2016, http://veja.abril.com.br/blog/radar-on-line/judiciario/se-eleicao-fosse-hoje-nancy-nao-se-elegeria-presidente-do-stj/.

- “CNJ investiga se juiz que bloqueou WhatsApp cometeu abuso de autoridade,” Revista Consultor Jurídico, May 3, 2016, http://www.conjur.com.br/2016-mai-03/cnj-abre-investigacao-conduta-juiz-bloqueou-whatsapp?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=facebook.

- Dias Toffoli, curriculum vitae, May 11, 2016, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/sobreStfComposicaoComposicaoPlenariaApresentacao/anexo/cv_dias_toffoli_11maio2016.pdf.

- Rodrigo Haidar, “Toffoli, candidato ao STF, não passou em concurso para juiz,” Revista Consultor Jurídico, June 8, 2008, http://www.conjur.com.br/2008-jun-05/toffoli_candidato_stf_nao_passou_concurso_juiz.

- The Mensalão was the biggest scandal of the Lula da Silva administration. An investigation into the Brazilian Postal Service uncovered large monthly payments made by the executive to federal legislators to get them to vote in accordance with the wishes of the executive branch.

- “Criminal Case no. 470,” Supremo Tribunal Federal, 2012, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/noticianoticiastf/anexo/relatoriomensalao.pdf.

- Partido Comunista do Brasil vs. Câmara dos Deputados, “ADPF no. 378/2015,” Supremo Tribunal Federal, 2015, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/noticiaNoticiaStf/anexo/adpf378.pdf.

- Despite some claims to the contrary, Rousseff’s impeachment was not a coup. The impeachment process and the “responsibility” crimes for which a Brazilian president can be impeached are outlined in articles 85 and 86 of the constitution. One of those impeachable offenses is violation of the budgetary law. The independent Federal Accounts Court found that the Rousseff administration had broken the law by fiddling with the budget. In fairness, previous presidents had committed the same crime—although not to the same extent as Rousseff—without facing political consequences. Impeaching Rousseff was certainly a political decision, but the process was legally sound, as demonstrated by the Supreme Court’s finding of no fault in the way it was conducted. It is important to note that, at the time, eight of the eleven justices on the Supreme Court had been appointed by Rousseff and her Workers’ Party predecessor, Lula da Silva. See Diogo Costa and Magno Karl, “Dilma Rousseff’s Impeachment Wouldn’t Be a Coup,” Forbes, April 28, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2016/04/28/dilma-rousseffs-impeachment-wouldnt-be-a-coup/.

- Secretariat of Social Communication, Prosecutor General’s Office, Roberto Gurgel destaca independência, modernização e união do MP, MPF’s newsletter, August 15, 2011, http://noticias.pgr.mpf.mp.br/noticias/noticias-do-site/copy_of_geral/roberto-gurgel-destaca-independencia-modernizacao-e-uniao-do-ministerio-publico.

- Juliana Dal Piva, “A eleição de Janot foi uma resposta da classe,” Estadão, August 30, 2015, http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,a-eleicao-de-janot-foi-uma-resposta-da-classe,1753037. This tradition was recently broken by President Michel Temmer, who picked the candidate with the second most votes from the list submitted to him.

- Estadão Conteúdo, “’Isso é problema dele, não meu,’ afirma Janot sobre Lula ministro,” Zero Hora, March 16, 2016, http://zh.clicrbs.com.br/rs/noticias/noticia/2016/03/isso-e-problema-dele-nao-meu-afirma-janot-sobre-lula-ministro-5112913.html.

- Rede TV, “Janot responde à crítica de Lula dizendo que estudou para ser procurador,” March 18, 2016, http://www.redetv.uol.com.br/atardeesua/videos/ultimos-programas/janot-responde-a-critica-de-lula-dizendo-que-estudou-para-ser-procurador4.

- “Act no. 13.047,” Presidência da República, December 2, 2014, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2014/Lei/L13047.htm.

- Mario Coelho, “Dilma edita MP que agrada delegados da PF,” Congresso em Foco, October 14, 2014, http://congressoemfoco.uol.com.br/noticias/dilma-edita-mp-que-agrada-delegados-da-pf/.

- Jailton de Carvalho, “Polícia Federal cria força-tarefa para investigar parlamentares,” O Globo, March 6, 2016, http://oglobo.globo.com/brasil/policia-federal-cria-forca-tarefa-para-investigar-parlamentares-15521143.

- Receita Federal, “Brasil se destaca em operação

internacional coordenada pela Organização Mundial das Aduanas,” press release, December 17, 2015, http://idg.receita.fazenda.gov.br/noticias/ascom/2015/dezembro/brasil-se-destaca-em-operacao-internacional-coordenada-pela-organizacao-mundial-das-aduanas. - Policia Federal do Brasil, Estatística

de Operações, http://www.pf.gov.br/agencia/estatisticas. - The official task force dedicated to the Operation Car Wash within the PF ended its work in accordance with its schedule, officially shutting down on July 6, 2017. The focus now is inside the MPF, where the task force dedicated to the operation is still expanding, with an expected 200 percent increase in the prosecutors’ budget for 2018. See Rafael Moraes Moura, “MPF triplica orçamento da Lava Jato e aprova alta salarial de 16%,” Exame, July 25, 2017, http://exame.abril.com.br/brasil/conselho-do-mpf-amplia-orcamento-para-lava-jato-em-2018/.

About the Author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.