The European Union (EU) is a culmination of a long process of economic and political integration among European states. The EU started as a free trade area and a customs union. Over time, it has become a supranational entity that resembles a federal state and is governed by a byzantine bureaucracy in Brussels. The EU claims to have brought about prosperity and stability in Europe, but those claims are increasingly at odds with reality. Europe is becoming worryingly unstable and is falling behind other regions in terms of economic growth. The EU model, which is marked by overregulation and centralization, seems increasingly out of place in today’s world. What European countries need in the coming decades is openness, rather than regional protectionism, and flexibility, rather than overregulation from Brussels. Above all, what European governments need to do is to reconnect with their increasingly restless electorates, rather than ignore the latter for the sake of the unwanted goal of a European superstate.

Introduction

What is the European Union, and what has it accomplished? This is how the EU answers those questions: “The EU is unlike anything else—it isn’t a government, an association of states, or an international organization. Rather, the 28 Member States have relinquished part of their sovereignty to EU institutions, with many decisions made at the European level. The European Union has delivered more than 60 years of peace, stability, and prosperity in Europe, helped raise our citizens’ living standards, launched a single European currency (the euro), and is progressively building a single Europe-wide free market for goods, services, people, and capital” (my emphasis).1

This self-congratulatory assessment of the EU’s achievements is deeply problematic. Consider peace and stability. The EU’s narrative ignores, for example, the roles played by Germany’s unconditional surrender, Anglo-American occupation of West Germany, the rise of the communist threat in the East, and the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—all of which preceded the creation of the first and extremely tentative pan-European institutions. It also ignores the EU’s failure to deal with the Yugoslav crisis in the early 1990s, which was eventually “resolved” by the application of American military strength. Moreover, many Europeans see the EU as responsible for the growing instability in Europe. As will be explained in greater detail below, they see monetary policy as a source of friction between nation states, with the relatively well-off Germany and Austria on one side, and the failing Greece and stagnating Italy on the other side. The same is true of the EU’s failure to come up with an effective response to the recent wave of immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa, thus pitting the generally welcoming German government against the unwelcoming governments in Central and Eastern Europe.

Consider, also, prosperity. The role of the Marshall Plan in stimulating economic growth is, at best, controversial, but omitting it altogether from the EU’s narrative of Europe’s post-war recovery is self-serving.2 Similarly, Western European economies began to recover, as was to be expected, when the war ended and long before the birth of the first and extremely weak pan-European institutions. In fact, Western European economies experienced their most rapid expansion a decade before the first intra-European barriers to trade started to come down. That is not to say that intra-European trade liberalization was not beneficial. It was, beginning in the 1960s. In the meantime, Western Europe benefited from domestic reforms, such as Ludwig Erhard’s liberalization of the West German economy in 1948, and the global reduction of tariffs under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which started in 1947. The official EU narrative tends to omit all of the above inconvenient facts.

That is not to deny the strong desire for peace and prosperity among European peoples and their leadership after World War II. Rather, it will be argued that the EU institutions were, for the most part, ineffectual, and have increasingly become liabilities. As the example of Switzerland shows, there is no a priori reason to think that a looser cooperation between European states is incompatible with peace and prosperity.

Brief History of the European Integration Process

The humble origins of the EU date back to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, which aimed to create a “common” market for coal and steel among its member states. The Treaty of Rome, signed in 1957, took economic integration a step further. The European Economic Community (EEC) created a common market and a customs union for the six original EU members: Belgium, France, Holland, Italy, Luxembourg, and West Germany. In return for partial liberalization of the movement of goods, services, people, and capital, the EEC members agreed to a French demand for central planning in agriculture, known as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).3 The CAP included price controls and production quotas that will be discussed, at greater length, below.

Over time, the EEC became synonymous with Western Europe’s post-war prosperity. While the two were partially coterminous, the former did not cause the latter. Research shows that the post-war boom in Western Europe was a result of reconstruction and internal economic reforms.4 Moreover, the positive effects of the reduction in intra-European tariffs under the EEC cannot be divorced from the positive effects of the reduction in global tariffs under the GATT. The two were happening at the same time. Still, even a generous interpretation of the role of the EEC on growth in Western Europe after 1958 must accept that, by that time the EEC was established, Western Europe was already well on its way to prosperity.

As an example, take West Germany. The West German post-war recovery started in 1948, when Ludwig Erhard reformed the currency and removed the Nazi price and wage controls, which had been kept in place by the victorious allies. The EEC came into effect in 1958 and intra-European tariffs on trade were not fully eliminated until 1968—two decades after the beginning of the West German miracle.5 The EU and its precursors could not have been responsible for returning West Germany to growth or for its economic expansion during the 1950s.

Whatever the salutary effects of the EEC actually were, they did not last. By the mid- to late 1970s, West German Wirtschaftswunder, French trente glorieuses, and Italy’s il miracolo economico came to an end as stagflation set in. Far for being credited with Europe’s post-war prosperity, the EEC was considered a disappointment. It did not, contrary to popular opinion, upend protectionist policies among European nations and bring about higher growth.6 The Dooge Report of 1985 called for a fresh start. Under the Single European Act (SEA) of 1986, the national veto was replaced with qualified majority voting and European institutions were tasked with turning the common market into a truly free “single market.”7

The Single European Act of 1986 turned out to be a double-edged sword. The European Commission successfully broke down many internal barriers to trade. As a consequence, trade in goods is now largely free. The EU has also liberalized the movement of capital, and the Schengen Agreement, which was incorporated into the EU law by the Amsterdam Treaty of 1999, greatly liberalized the movement of people. When it comes to services, however, protectionism continues to reign. In the early 2000s, Frits Bolkestein, who was the EU Commissioner for the Internal Market, proposed the so-called Bolkestein directive, which would have greatly liberalized trade in services in the EU. His initiative failed.8 That is particularly disappointing, considering that services account for a majority of economic output in all EU economies.

The European institutions also used their new powers to overregulate economic activity. This process gathered speed after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, which transformed the EEC into the EU. Hundreds of thousands of directives and regulations—dealing with everything from the labor market to the electric power consumption of toasters—poured and keep pouring out of Brussels.9 Today, many EU countries, including its richest and most competitive members such as Great Britain and Germany, regularly complain about decrees from Brussels.10 Thus, while Brussels managed to break down many economic barriers within the EU, it also made the EU less competitive vis-á-vis the rest of the world.11

From a humble free-trade area and a customs union among six Western European countries, the EU has grown into a supranational entity that governs many aspects of the daily lives of 508 million people spread across 28 European countries. While lacking sovereign power, the EU has its own flag, anthem, currency, president (five of them, actually), and a diplomatic service. Today, the EU is trying to grasp new powers, while, paradoxically, it is also facing mounting opposition and a growing probability of collapse. How did the EU get here?

Mounting Failures

There is an overwhelming consensus among economists that free trade stimulates economic growth.12 In fact, no country has ever become rich in isolation. Unfortunately, trade liberalization in Western Europe was a slow and uneven process. The actual benefits of intra-European trade liberalization are difficult to estimate, because intra-European trade liberalization was taking place alongside global trade liberalization.13 That process had begun, at the insistence of the United States, in 1947—eleven years before the creation of the EEC.

Over time, intra-EU trade relative to trade with the rest of the world has grown less, not more, important to European prosperity. The costs of communications, financial transfers, and transportation have been greatly reduced since World War II, making global trade increasingly lucrative. Trade between the United States and the EU, for example, continues to grow, even though there is no free-trade agreement between the two.14 Similarly, British exports to the EU are growing at a slower pace than British exports to non-EU countries.15

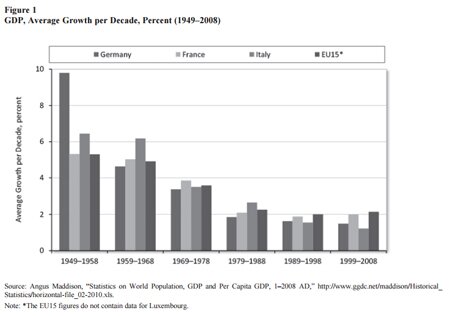

Moreover, the economic benefits of intra-European trade have been undermined by overregulation. As centralization of decisionmaking in Brussels increased, Western European growth has declined (see Figure 1). Today, much of Europe is not growing at all. Some of Europe’s woes have nothing to do with the EU and are connected to changing demographics—low birth rates and an aging population. Yet Europe has also suffered from a number of self-inflicted wounds that go beyond overregulation.

The CAP, for example, has resulted in mountains of butter and lakes of milk. Those were later destroyed or dumped in Third World markets, where they undermined local producers.16 Accompanying the CAP was the Common Fisheries Policy that, instead of preserving Europe’s fish stocks through a quota system, nearly wiped them out. One Dutch study found that to maintain their quotas fishermen tipped “two to four tons of dead fish” overboard for every ton of fish headed for consumption.17

The Structural and Cohesion Funds (SCF), a system of transfer payments that used money from taxpayers in rich countries to try to spur growth and employment in Europe’s underdeveloped south, became a legendary boondoggle of financial misallocation and corruption.18 The European Court of Auditors has refused to sign off on the EU budget for 20 years in a row—citing irregularities.19

The euro was supposed to have led to increased growth, lower unemployment, and greater competitiveness and prosperity. According to “50 leading economists” who were brought together by the pro-EU Centre for European Reform, “there was a broad consensus that the euro had been a disappointment: the currency union’s economic performance was very poor, and rather than bringing EU member-states together and fostering a closer sense of unity and common identity, the euro had divided countries and eroded confidence in the EU.”20

In retrospect, it should be clear that the Eurozone was poorly designed. Its members have committed themselves to maintaining manageable levels of debt (capped at a maximum of 60 percent of GDP) and deficits (capped at a maximum of 3 percent per year). What the Eurozone lacked was a credible enforcement mechanism. Indeed, some of the biggest Eurozone members, including France and Germany, broke their debt and deficit commitments shortly after the launch of the common currency. Other countries followed suit.

Worse still, Eurozone membership has allowed some of Europe’s worst-managed economies to massively expand their debt by taking advantage of historically low interest rates. The markets lent money to Southern Europe, expecting that if problems arose they would be bailed out. The markets were correct. Thus, when the southern economies crashed, their creditors—chiefly European banks—were bailed out at a massive cost to the European taxpayer. As ever, a problem that was created by deeper integration has led to calls for “more Europe” and the establishment of a “fiscal union.”21

In recent years, another serious problem has emerged: the mismanagement of mass immigration from Africa and the Middle East. While immigration can be a force for good, European countries have been generally unsuccessful at integrating foreigners. Much of that failure has to do with government policies, such as extensive welfare provisions and labor-market restrictions that keep immigrants out of the workforce, and some have to do with a particularly European understanding of nationhood, which is based on ethnicity, not citizenship. Rightly or wrongly, the failure of Europe’s immigration policy, which has allowed for a large influx of foreigners whom Brussels is now trying to forcefully “redistribute” among the member states, has succeeded in awakening an epic level of resentment.22

The euro bailout and the mishandling of the immigration crisis have elucidated one of the least appreciated, but one of the most consequential negative aspects of European integration: the assault on the rule of law.

Clearly, Article 125 of the Lisbon Treaty states that each EU member state is responsible for its own debts. It is inconceivable that the Eurozone would ever have been born without that vital stipulation, which was necessary to assuage the concerns of the German electorate. Moreover, Article 123 prohibits the European Central Bank from buying sovereign bonds in primary markets and sovereign bonds in secondary markets—if the latter is done for fiscal, as opposed to monetary, reasons. Brussels and Frankfurt have ignored both stipulations in order to keep Greece in the Eurozone.23

Similarly, the Dublin Regulation specifies that asylum applications by those who seek protection in the EU under terms of the Geneva Convention must be examined and processed at the point of entry, which is to say by the first EU member state that they have arrived in.24 Greece, and to a lesser extent Italy, have failed to fulfill their obligations and allowed hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of asylum-seekers to migrate to other EU states, including Germany. The German government, in turn, has unilaterally decided to welcome these migrants only to then demand that they be proportionately distributed among other EU countries.

Putting the humanitarian question aside, even the EU member states which never received asylum-seekers, and which had no say in “letting” them into the EU at large, are now being forced to accommodate them.25 The member states have responded to the EU threats by breaking with their Schengen Area commitments and erecting barriers to keep the immigrants out—thus exacerbating the assault on the rule of law in Europe.

Democratic Deficit

In today’s political discourse, democracy is often understood as majoritarian decisionmaking. That view of democracy is problematic, for, as history shows, majorities, too, can be tyrannical. Majoritarian rule, therefore, needs to be constrained by separation of powers, checks and balances, and constitutional guarantees.

But the term “democracy” has another important meaning—the ability of the electorate to choose and replace the government through free and fair elections. The choice, however, needs to be a meaningful one. What is the point of being able to choose between two or more candidates if none of them can effect specific policy changes? What is the point of having a vote if the real decisionmakers are unelected, unknown, and unaccountable? Those are the questions that are at the root of the EU’s problem with the “democratic deficit.”

Over the years, EU member states have ceded a large number of policy areas, or “competences,” to the byzantine bureaucracy in Brussels. Some have been ceded completely, in which case elected public officials at the national level have no choice but to implement decisions made in Brussels. Some have been ceded partially, in which case elected public officials at the national level are limited in their ability to influence decisions made in Brussels. In both cases, the voters’ ability to effect changes of policy through their elected representatives and to hold those representatives responsible in free and fair elections is rendered meaningless.

The problem of the democratic deficit is compounded by two inconvenient facts. First, the nation-state remains the basic building block of international relations, including European. The national identities of European states have been evolving separately, and often in competition with one another, for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years. The Greeks were first unified by the Argead dynasty in the 4th century BCE. A relative newcomer, England, was first unified a thousand years ago and developed a set of unique institutions, such as parliamentary sovereignty, which does not exist on the continent.

Second, a pan-European demos does not exist. For a vast majority of European peoples, being a “European” remains a geographical, not a political, distinction. Thus, while European travelers to the United States may say that they are from Europe, in Europe they almost always refer to themselves as being from Britain, France, Germany, or whatever country they are from. That is likely to continue, because most people’s identities are not formed by attachment to abstract principles such as liberty, equality, and fraternity, but by cultural, religious, historical, and linguistic ties.26

Bearing those points in mind, it is crucial to realize that the EU is undemocratic not by accident, but by design. The proponents of “an ever closer union” understand that there is no public support for anything resembling the United States of Europe. Jean-Claude Juncker, the current President of the EU Commission, summed up the decisionmaking process in Brussels thusly: “We decide on something, leave it lying around and wait and see what happens. If no one kicks up a fuss, because most people don’t understand what has been decided, we continue step by step until there is no turning back.”27 When the French and the Dutch rebelled and voted against the EU Constitution in their 2005 referenda, they were ignored—and the EU Constitution, relabeled as the Lisbon Treaty, was adopted nevertheless.

Is it any surprise, therefore, that while the EU Commission and the EU Parliament grew in power and importance, the European peoples’ interest and participation in EU institutions have steadily declined? When the first election for the European Parliament was held in 1979, for example, 62 percent of eligible voters cast their vote. In every subsequent election, voter turnout has declined. It reached a nadir, 42.61 percent, in 2014.28

Rise of Populist Parties

Unwittingly, the EU has become a driving force behind the rise of populist parties in Europe. These parties come from across the political spectrum—from the far left to the far right. Often they have nothing in common except for their opposition to further European integration and a desire, at the very minimum, to repatriate some of the EU powers back to nation states. They are present in all EU countries and hold, remarkably, one-third of all seats in the European Parliament.

While some of these parties are more respectable than others, the EU often paints them with the same brush. Thus, people who happen to believe that the EU is a threat to liberal values, such as democratic accountability, are often treated with as much disdain as people who happen to believe in authoritarianism.

Consider the former vice president of the EU Commission, Margot Wallström. While visiting the Czech city of Terezin, which used to be a site of a Nazi concentration camp during World War II, Wallström linked the rejection of the EU Constitution to the return of the Holocaust. She said, “They [opponents of the EU Constitution] want the European Union to go back to the old purely intergovernmental way of doing things. I say those people should come to Terezin and see where that old road leads.”29

So, what are the reasons for the rise of populism in Europe? First, many Europeans, but especially the citizens of well-functioning democracies such as Denmark, Holland, and Great Britain, resent the democratic deficit. They feel that far too many decisions impacting their lives are being made in Brussels by people who are unelected, unknown, and unaccountable. This feeling is not as strong in the East, where democratic accountability is recent and deeply imperfect, but it is growing in countries such as the Czech Republic and Hungary.

Second, many Europeans see the EU as having failed in some of its core competences, including monetary and immigration policies. The Westerners do not wish to continue subsidizing the inefficient south, while the Easterners reject immigration from Africa and the Middle East. Calls for solidarity between European countries are resented and, increasingly, rejected.30 In the absence of a pan-European demos, citizens of Germany cannot understand why they should pay to bail out the Greeks, and citizens of Hungary cannot understand why they should take in some of the non-EU immigrants who have arrived in Germany.

Third, many Europeans feel a general sense of malaise and decline.31 To be fair, the blame for Europe’s woes does not rest with the EU alone. The national governments are also to blame. A growing number of Europeans are frustrated by the failure of the EU establishment and of the mainstream political parties at home to address low economic growth, high unemployment, mass immigration, and rising debt. By voting for populist parties, they are lashing out against the “establishment.”

Is EU Reform Possible?

The piecemeal amalgamation of 28 distinct cultures, polities, economies, and histories had proceeded apace in spite of a growing resentment among the European peoples.32 That process of unification may well have continued, unimpeded by popular sentiments, had the EU lived up to its own rhetoric and delivered prosperity and stability to the European continent. Regrettably, it has failed to deliver either.

Many thoughtful commentators have recognized the need for EU reforms. Many believe that such reform should include at least some repatriation of EU powers back to the nation states. Unfortunately, past experience with EU reform does not augur well for the future.

In 2000, for example, the Lisbon Agenda committed the EU to becoming “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion” by 2010.33 Nothing was done to reverse decades of EU overregulation and the Swedish Presidency of the EU declared the Lisbon Agenda a failure in 2009.34

The Lisbon Agenda was replaced by a reform program called Europe 2020. According to the EU Commission itself, “The [2008] crisis has wiped out years of economic and social progress and exposed structural weaknesses in Europe's economy. In the meantime, the world is moving fast and long-term challenges—globalization, pressure on resources, ageing—intensify.”35 Astonishingly, the document does not mention deregulation at all and the only reference to global competitiveness is in the context of the EU support for “the development of a strong and sustainable industrial base.”36 This is a thin gruel indeed!

In fact, the EU has shown itself incapable of serious reform even when faced with possible disintegration. Prime Minister David Cameron’s desire to “fundamentally change” Great Britain’s relationship with the EU has met with stubborn refusal in Brussels to consider anything but cosmetic modifications to existing treaties.37 For example, Cameron asked for national parliaments to have the ability to block legislation originating in Brussels. What he got instead was a promise that if more than 50 percent of EU parliaments raise concerns over an EU proposal, the EU Commission will reconsider it. This “red card” process is immensely difficult to implement and, probably, legally unenforceable.38 Considering that the EU has refused to reform with the British referendum on EU membership hanging, so to speak, over its head, what’s the likelihood that the EU will reform once the danger of Brexit has passed?

The real problem for those who wish to see EU reforms is that the EU establishment has a strong incentive to centralize decisionmaking in Brussels rather than decentralize. Quite aside from the ideological commitment of the EU bureaucrats to the creation of a United States of Europe, which they may or may not believe in, centralization of power is in their interest. It increases their power and resources.

Yet, a blueprint for reform is available, for there is a European country that has not experienced international conflict since 1815 or civil strife since 1848; a country that trades freely with the EU, but also with the rest of the world; a country that is richer than all EU countries, except for Luxemburg; and a country that maintains a world-beating degree of domestic harmony and democratic accountability; a country that is not a part of the EU’s political or economic integration process, but which deals with the EU at an intergovernmental level via a series of bilateral treaties. That country is Switzerland.

European Union’s Greatest Achievement?

It is often claimed that the EU expansion into ex-communist countries was one of its greatest accomplishments. As one author notes, “the prospect of European integration created pressure to reform Eastern European economies and strengthen the rule of law.”39

That is partially true. In Slovakia, for example, the prospect of the EU membership certainly played a part in defeating an authoritarian and protectionist government and replacing it with one committed to democratic and economic reforms.40 In the economically free Estonia, on the other hand, EU membership meant reimposition of tariffs and a consequent partial decline in economic freedom.41

Still, there is no denying that all ex-communist members of the EU enjoy a higher degree of political freedom than non-EU ex-communist countries, such as Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Ukraine, let alone the politically unfree Belarus.42 Electoral shenanigans are rare and governments come and go in accordance with the will of the people. That is, after all, why they were admitted into the EU in the first place.

But, when it comes to the creation of “liberal democracy,” the picture is, at best, mixed. In general, the rule of law has improved and corruption declined in ex-communist countries during the EU accession talks. Unfortunately, these salutary trends have stalled since the ex-communist countries entered the EU.43 Indeed, some evidence suggests that disbursement of Structural and Cohesion funds has exacerbated ex-communist countries’ problem with corruption.44

Last, but not least, consider the impact of EU regulations on ex-communist countries. Productivity across the EU differs widely. In 2015, for example, GDP per capita in Luxembourg, the EU’s richest state, was 14.9 times higher than that in Bulgaria, the EU’s poorest state. In contrast, GDP per capita in North Dakota, which is America’s richest state, is only slightly more than 2.1 times higher than that in Mississippi, America’s poorest state.45

By definition, regulations emanating from Brussels must be applied equally throughout the EU. Unavoidably, regulations that add to the cost of production have a more deleterious effect on less productive ex-communist countries than on more productive Western European nations. Eastern countries are growing increasingly resentful of regulations, which are often made to enhance the already high standards that exist in the West and which are often meant to protect the interests of Western producers.

Conclusion

I started my career as a believer in the European integration process. Central Europe, where I was born, was impoverished by communism, and membership of the EU seemed like a solution to many economic and political problems in ex-communist countries. Over time, I started to see the costs as well as the benefits of the EU. It was only much later that I came to believe that the costs of EU membership far outweigh its benefits. While this was a gradual process, one event greatly helped to convince me that the EU has become pernicious and must be stopped. That event was the EU’s handling of the French and Dutch referenda on the EU Constitution in 2005.

After the people of France and Holland rejected the EU Constitution in their respective referenda, the EU establishment relabeled it as the Lisbon Treaty and adopted it nonetheless. This act of supreme arrogance convinced me that the EU establishment held the people of Europe in utter contempt and that it would stop at nothing in order to pursue its agenda of an “ever closer union.” It showed me that the EU bureaucrats see themselves as a class of wise experts who know how society ought to be organized. The memories of my childhood behind the Iron Curtain flooded back. And that brings me to my final point: does an “enlightened” class of technocrats have a right to make people free or happy or, simply, better off?

As I have explained, the EU is not only failing to address Europe’s problems, it exacerbates them. Moreover, it seems to be unable and unwilling to reform. With every electoral cycle, “establishment” parties committed to further European integration are growing weaker and anti-EU parties are getting closer to power. The EU has been very successful in plodding along, but its rearguard action cannot succeed indefinitely. At some point, one of the EU’s 28 member states will elect an anti-EU government. I fear that the longer the EU establishment ignores its opponents, the more belligerent the latter will become.

As such, a negotiated parting of ways between the EU and countries that feel they can do better on their own makes more sense. Of course, there is no guarantee that all of the former EU members will make the right choices. I can imagine Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Great Britain becoming a global free-trade superpower. But, I can also imagine President Marine Le Pen’s France hunkering down behind a wall of protective tariffs. That said, I would rather see individual nation states make wrong choices than to force them to remain in the EU, thus increasing resentment and risking greater disruption down the line.

The EU has become a large pressure cooker with no safety valve. Large parts of Europe suffer from low growth, high unemployment, rising deficits, and stratospheric debts. To make matters worse, tensions between the people of Europe are increasing. Some feel that they are being forced to adopt policies they do not like, while others feel that they have to unfairly subsidize people with whom they have nothing in common. The EU could turn down the heat by repatriating many of its competences back to the nation states. That, alas, is not in its nature. The EU risks imploding in an uncontrolled way and if that happens, everyone will lose.

Notes

1. Delegation of the European Union to the United States, “What is the European Union?” http://www.euintheus.org/who-we-are/what-is-the-european-union/.

2. Doug Bandow, “A Look Behind the Marshall Plan Mythology,” Investor’s Business Daily, June 3, 1997, http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/look-behind-marshall-plan-mythology.

3. John Gillingham, European Integration, 1950–2003: Superstate or New Market Economy? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 197.

4. Richard Reichel, “Germany’s Postwar Growth: Miracle or Reconstruction Boom,” Cato Journal 21, no. 3 (Winter 2002): 427–42.

5. “The Abolition of Customs Barriers to Trade in the EU,” Europedia, http://www.europedia.moussis.eu/books/Book_2/3/5/1/1/?all=1.

6. Natalie Chen and Dennis Novy, “Barriers to Trade Within the European Union,” University of Warwick, https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/eri/bulletin/2008-09-3/chen-novy/.

7. “The European Single Market,” EU Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/index_en.htm.

8. “‘Bolkestein Directive’ to Stay, but Will be Watered Down,” Euractiv, March 23, 2005, http://www.euractiv.com/section/innovation-industry/news/bolkestein-directive-to-stay-but-will-be-watered-down/.

9. Matthew Holehouse, “EU to Launch Kettle and Toaster Crackdown after Brexit Vote,” Daily Telegraph (London), May 11, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/05/10/eu-to-launch-kettle-and-toaster-crackdown-after-brexit-vote2/.

10. Szu Ping Chan, “Germany Pleads with UK to Remain in EU to Fight Red Tape,” Daily Telegraph (London), July 4, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11718554/Germany-pleas-with-UK-to-remain-in-EU-to-fight-red-tape.html.

11. Lisa Urquhart, “Regulations Will 'Make Europe Less Competitive',” Financial Times (London), November 18, 2005, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8954808c-57d7-11da-8866-00000e25118c.html.

12. Gregory Mankiw, “Economists Actually Agree on This: The Wisdom of Free Trade,” New York Times, April 24, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/26/upshot/economists-actually-agree-on-this-point-the-wisdom-of-free-trade.html.

13. World Trade Organization, The Text of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (Geneva: WTO, 1986), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/gatt47.pdf.

14. Jayson Beckman, “U.S. Beef Exports to the EU Grow Despite Trade Barriers,” United States Department of Agriculture, April 6, 2015, http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2015-april/us-beef-exports-to-the-eu-grow-despite-trade-barriers.

15. Peter Spence, “The EU's Dwindling Importance to UK Trade in Three Charts,” Daily Telegraph (London), June 26, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11700443/The-EUs-dwindling-importance-to-UK-trade-in-three-charts.html.

16. Oxfam International, Dumping on the World: How EU Sugar Policies Hurt Poor Countries,” Oxfam Briefing Paper no. 61 (March 2004), https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/bp61_sugar_dumping_0.pdf.

17. F. A. van Beek, “Discarding in the Dutch Beam Trawl Fishery,” International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (1998), Flanders Marine Institute, www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/138419.pdf.

18. Dalibor Rohac, “How the European Union Corrupted Eastern Europe,” National Review, March 26, 2014, http://www.nationalreview.com/agenda/378798/how-european-union-corrupted-eastern-europe-dalibor-rohac.

19. Benjamin Fox, “Auditors Refuse to Sign Off EU Spending For 20th Year in a Row,” EU Observer (Brussels), November 6, 2014, https://euobserver.com/news/126405.

20. Simon Tilford, John Springford, and Christian Odendahl, “Has the Euro Been a Failure?” Centre for European Reform, January 11, 2016, https://www.cer.org.uk/publications/archive/report/2016/has-euro-been-failure.

21. Justin Huggler, “French Economy Minister Calls for Full Fiscal Union in Eurozone,” Daily Telegraph (London), August 31, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11835614/French-economy-minister-calls-for-full-fiscal-union-in-eurozone.html.

22. Voice of America, “Anti-Migrant Protesters Rally in Several Major European Cities,” VOA, February 6, 2016, http://www.voanews.com/content/anti-migrant-protesters-rally-european-cities/3179948.html.

23. “Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,” Eurlex, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT.

24. “Country Responsible for Asylum Application (Dublin),” EU Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/asylum/examination-of-applicants/index_en.htm.

25. Matthew Holehouse, “EU to Fine Countries 'Hundreds of Millions of Pounds' for Refusing to Take Refugees,” Daily Telegraph (London), May 3, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/05/03/eu-to-fine-countries-that-refuse-refugee-quota/.

26. European Commission, “European Citizenship,” Standard Eurobarometer no. 77 (Spring 2012), http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb77/eb77_citizen_en.pdf.

27. Bruno Waterfield, “Jean-Claude Juncker Profile: 'When it Becomes Serious, You Have to Lie',” Daily Telegraph (London), November 12, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/eu/10874230/Jean-Claude-Juncker-profile-When-it-becomes-serious-you-have-to-lie.html.

28. “Results of the 2014 European Elections,” EU Parliament, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/elections2014-results/en/turnout.html.

29. Raphael Minder, “Commissioner under Fire Over 'Nazi' Speech,” Financial Times (London), May 13, 2005, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/11f37e2e-c34b-11d9-abf1-00000e2511c8.html

30. Marian L. Tupy and Richard Sulik, “The Limits of European Solidarity,” Wall Street Journal, February 15, 2012, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204795304577222833332928436.

31. Tony Barber, “The Decline of Europe Is a Global Concern,” Financial Times (London), December 21, 2015, https://next.ft.com/content/ddfd47e8-a404-11e5-873f-68411a84f346.

32. Lionel Beehner, “European Union: The French and Dutch Referendums,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 1, 2005, http://www.cfr.org/france/european-union-french-dutch-referendums/p8148.

33. European Parliament, “Lisbon European Council 23 and 24 March 2000: Presidency Conclusions,” http://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_en.htm.

34. “Sweden Admits Lisbon Agenda ‘Failure’,” June 3, 2009, Euractiv, http://www.euractiv.com/section/eu-priorities-2020/news/sweden-admits-lisbon-agenda-failure/.

35. European Commission, “Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth,” March 3, 2010, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020:FIN:EN:PDF.

36. Ibid.

37. British Broadcasting Corporation, “EU Talks: Cameron Says UK Will Get New Deal in 2016,” December 18, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-35135049.

38. Mark Wallace, “The Gap between What Cameron Asked For and What He Got,” Conservative Home, February 3, 2016, http://www.conservativehome.com/thetorydiary/2016/02/the-gap-between-what-cameron-asked-for-and-what-he-got.html.

39. Dalibor Rohac, “I Used to be Eurosceptic. Here’s Why I Changed My Mind,” American Enterprise Institute, March 30, 2016, https://www.aei.org/publication/i-used-to-be-euroskeptic-heres-why-i-changed-my-mind/.

40. European Parliament, “Slovakia and the Enlargement of the European Union,” Briefing no. 13 (2000), http://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/briefings/13a2_en.htm.

41. Marian L. Tupy, “At What Cost EU Membership?” Wall Street Journal, April 29, 2012, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303916904577373773633684722.

42. Freedom House, “Freedom in the World 2016,” https://www.freedomhouse.org/report-types/freedom-world.

43. World Bank, “The Worldwide Governance Indicators,” http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home.

44. Rohac, “How the European Union Corrupted Eastern Europe.”

45. World Bank, “GDP per capita, PPP (current international $),” http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD.