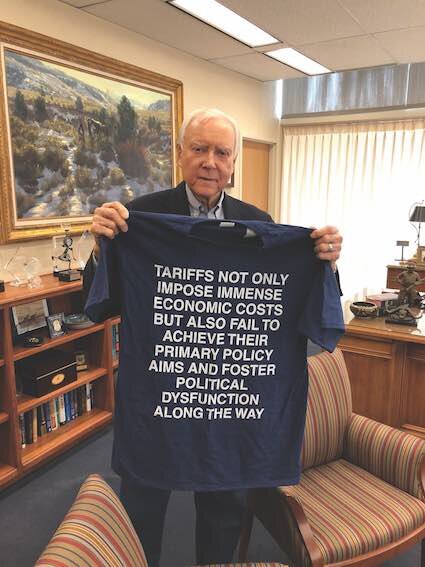

What began as a pro–free trade Twitter quip from Cato trade policy analyst Scott Lincicome turned into a viral T‑shirt that has been purchased over 700 times — including by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R‑UT), who displayed it proudly in a photo that appeared in a tweet from Hatch and on Meet the Press. (See page 1).

In a photo tweeted by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R‑UT) and later featured on Meet the Press, the senator holds up a T‑shirt inspired by Cato trade policy analyst Scott Lincicome. Over 700 of these shirts have been sold since a pro–free trade Twitter quip from Lincicome went viral.

It all started when Lincicome spotted a T‑shirt worn by a woman at a Trump rally, which read “Tariff hikes will be GREAT.” Over the past several months, the Trump administration has imposed massive tariffs on steel and aluminum, as well as on hundreds of Chinese electronics, aerospace products, and machinery. Dismayed by these developments, and by the T‑shirt’s blithe economic ignorance, Lincicome made a mock-up of his own version of the shirt, reading, “Tariffs not only impose immense economic costs but also fail to achieve their primary policy aims and foster political dysfunction along the way.” Amused by the verbose — but accurate — rebuttal, other Twitter users began spreading it as a hashtag: #TNOIIECBAFTATPPAAFPDATW. As the joke and hashtag picked up steam, a fellow trade enthusiast began selling real-life versions of Lincicome’s T‑shirts on Amazon, and has since sold over 700, with proceeds benefiting the Foundation for Economic Education.

Whether Cato’s scholars are inspiring viral Twitter hashtags or delving into serious research on how proposed trade deals would impact the economy, the confusion and myths that now abound surrounding trade policy make the expert advocacy of Cato’s Herbert A. Stiefel Center for Trade Policy Studies more necessary than ever. The center’s experts have been at the forefront of the policy debate in recent months, advocating for free trade in regular appearances in major newspapers such as the Washington Post and the New York Times and on networks including the BBC, NPR, NBC, Fox, and CNN.

As Daniel Ikenson, the director of the center, told NBC, Trump’s latest trade measures are “likely to raise production costs for U.S. businesses, diminish U.S. productivity, squeeze real household incomes, reduce the revenues of U.S. farmers and other export-dependent industries targeted by Chinese retaliation, exacerbate tensions with China and other countries adversely affected by the restrictions, and hasten the demise of the rules-based trading system.” While President Trump has claimed that trade wars are “good, and easy to win,” this is refuted by centuries of American history, as Lincicome detailed in his 2017 Cato Policy Analysis, “Doomed to Repeat It: The Long History of America’s Protectionist Failures.” Lincicome told Politico that “Going back 100 years and even dating to the Civil War, you look at the academic analysis of protectionism and the results are pretty much uniformly the same. You have far more costs than benefits and those costs are borne not just by consumers but by American companies and farmers and exporters.”

With new concerning trade policies emerging from this administration at a rapid pace in recent months, Cato scholars’ quick analysis is an invaluable resource for the media and the public: a February Washington Post article praised Lincicome’s “epic tweetstorm last week documenting the myriad ways the 2018 Economic Report of the President subverts Trump’s trade rhetoric.” The article went on to cite the many passages that, as Lincicome noted, offer a “stunning rebuke” of the president’s own erroneous beliefs on trade — such as “Historically, international trade as a whole has on net increased American productivity, standards of living, and American economic growth.”

It’s hardly surprising that even a White House economic report would make these statements — free trade is one of the rare political areas where there is, in fact, a strong academic consensus across ideologies. As Fareed Zakaria noted on his CNN show, “Trump’s tariffs are opposed by a remarkable array of scholars across the political spectrum, from the conservative Heritage Foundation, to the libertarian Cato Institute, to the center-left Brookings Institution, to the left-wing Center for Economic and Policy Research.” It’s time that politicians acknowledge what scholars already know: free trade is good for everyone.