One of America’s foundational constitutional guarantees is that the justice system does its work in public. Under the Sixth Amendment, secret trials are forbidden, and under the First Amendment, we are all free to criticize the government’s conduct in enforcing its laws. If the state wants to punish somebody, it must lay out its case in full view of public scrutiny and subject to public rebuttal. This requirement is crucial not just to prevent individual injustices but also to allow self-governing people to observe what is being done in their name. Organizing intellectual and political opposition to government abuses is difficult at best if the victims are forcibly silenced.

Yet that is precisely what the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and other regulatory agencies have been doing as a matter of routine policy. The SEC is using the settlement of civil enforcement actions, often in parallel with criminal charges by the Department of Justice, to permanently silence those it accuses of illicit conduct. Under this requirement, those who accept settlements — as happens in 98 percent of cases — are required to agree that they will never make "any public statement denying, directly or indirectly, any allegation in the SEC's complaint or creating the impression that the complaint is without factual basis." In effect, this amounts to a lifetime gag order that makes it impossible for those targeted for enforcement by these agencies to speak out and tell their side of the story.

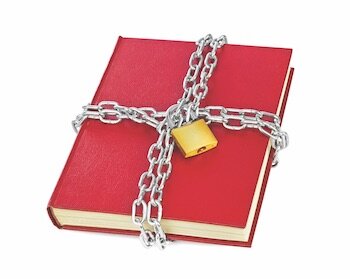

Clark Neily, Cato's vice president for criminal justice, was approached by just such a defendant, who believes he was unjustly targeted by the SEC. This defendant believes his case was an abuse of prosecutorial discretion and an example of misconduct on the part of the SEC. Like most people in his situation, he accepted the settlement under threat of the ruinous litigation costs that would entail from mounting a defense in court. This defendant, whose identity is known to Cato, has written a book about his experiences. Cato's criminal justice scholars found his story compelling and would like to publish his book but cannot without the government renewing its case against him.

With representation from the — merry band of litigators — at the Institute for Justice, Cato is filing suit against the SEC to vindicate Cato's own First Amendment rights and to challenge the constitutionality of these lifetime gag orders. In an era where the First Amendment is often tested by new contexts and novel technologies, Cato v. SEC seeks to vindicate a core protection that would be perfectly recognizable to James Madison: the right to publish a book that the government doesn't like.