1. “History of Progress,” HumanProgress.org, accessed April 11, 2023; Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Human Development and the Path to Freedom (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022); Prados de la Escosura, “Augmented Human Development in the Age of Globalization,” The Economic History Review 74, no. 4 (2021): 946–75; and Lant Pritchett, “Development Happened. Did Aid Help?,” Oxford Blavatnik School of Government and LSE, March 10, 2022.

2. Fabian T. Pfeffer and Nora Waitkus, “The Wealth Inequality of Nations,” American Sociological Review 86, no. 4 (2021): 567–602; Marianne Nordli Hansen and Maren Toft, “Wealth Accumulation and Opportunity Hoarding: Class-Origin Wealth Gaps over a Quarter of a Century in a Scandinavian Country,” American Sociological Review 86, no. 4 (2021): 603–38; and Jan Schulz, Daniel M. Mayerhoffer, and Anna Gebhard, “A Network-Based Explanation of Inequality Perceptions,” Social Networks 70 (2022): 306–24.

3. Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Viking Books, 2018), p. 97.

4. See Google Books Ngram viewer, accessed April 11, 2023.

5. Jan Schulz, Daniel M. Mayerhoffer, and Anna Gebhard, “A Network-Based Explanation of Inequality Perceptions,” Social Networks 70 (2022): 306–24; and Hans Rosling, Factfulness (Paris: Flammarion, 2019).

6. Soondong Hong, Heejoon Han, and Chang Sik Kim, “World Distribution of Income for 1970–2010: Dramatic Reduction in World Income Inequality during the 2000s,” Empirical Economics 59, no. 2 (2020): 765–98; and Branko Milanovic, “Global Income Inequality by the Numbers: In History and Now—an Overview,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 6259, November 1, 2012.

7. Vincent Geloso and Phillip Magness, “The Great Overestimation: Tax Data and Inequality Measurements in the United States, 1913–1943,” Economic Inquiry 58, no. 2 (2020): 834–55; Vincent J. Geloso, Phillip Magness, John Moore, and Philip Schlosser, “How Pronounced Is the U‑Curve? Revisiting Income Inequality in the United States, 1917–60,” Economic Journal 132, no. 647 (2022): 2366–91; Gerald Auten and David Splinter, “Top 1 Percent Income Shares: Comparing Estimates Using Tax Data,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109 (2019): 307–11; Jeff Larrimore, Richard Valentine Burkhauser, Gerald Auten, and Philip Armour, “Recent Trends in US Income Distributions in Tax Record Data Using More Comprehensive Measures of Income Including Real Accrued Capital Gains,” Journal of Political Economy 129, no. 5 (2021): 1319–60; George Mechling, Stephen Miller, and Ron Konecny, “Do Piketty and Saez Misstate Income Inequality? Critiquing the Critiques,” Review of Political Economy 29, no. 1 (2017): 30–46; and Vincent Geloso and Peter Lindert, “Relative Costs of Living, for Richer and Poorer, 1688–1914,” Cliometrica 14, no. 3 (2020): 417–42.

8. Amartya Sen, The Standard of Living (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Amartya Sen, “Markets and Freedoms: Achievements and Limitations of the Market Mechanism in Promoting Individual Freedoms,” Oxford Economic Papers (1993): 519–41; and Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001).

9. Peter Thomas Bauer, From Subsistence to Exchange and Other Essays (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), pp. 30–31.

10. Nicholas Eberstadt, “Longevity, Education, and the Huge New Worldwide Increases in Equality,” in Anti-Piketty: Capital for the 21st Century, ed. Jean-Philippe Delsol, Nicolas Lecaussin, and Emmanuel Martin (Washington: Cato Institute, 2017).

11. Sam Peltzman, “Mortality Inequality,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23, no. 4 (2009): 175–90; and Benjamin Ho and Sita Nataraj Slavov, “An Alternative Perspective on Health Inequality,” Economics Bulletin 32, no. 4 (2012): 3182–96.

12. Andrew Dabalen, Ambar Narayan, Jaime Saavedra-Chanduvi, and Alejandro Hoyos Suarez, Do African Children Have an Equal Chance?: A Human Opportunity Report for Sub-Saharan Africa (Washington: World Bank Group, 2015), p. 28; and Giovanni Andrea Cornia, ed., Inequality, Growth, and Poverty in an Era of Liberalization and Globalization (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004).

13. Clio-Infra Project, “Educational Inequality Gini Coefficient,” https://clio-infra.eu/Indicators/EducationalInequalityGiniCoefficient.html.

14. Benaabdelaali Wail, Said Hanchane, and Abdelhak Kamal, “A New Data Set of Educational Inequality in the World, 1950–2010: Gini Index of Education by Age Group,” SSRN Electronic Journal (2011); and Benaabdelaali Wail, Said Hanchane, and Abdelhak Kamal, “Chapter 13 Educational Inequality in the World, 1950–2010: Estimates from a New Dataset,” in Inequality, Mobility and Segregation: Essays in Honor of Jacques Silber, ed. John A. Bishop and Rafael Salas (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing, 2012).

15. Lauri Peterson, “The Measurement of Non-economic Inequality in Well-Being Indices,” Social Indicators Research 119 (2014), 581–98; and “Human Development Index (HDI),” United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports, accessed April 11, 2023.

16. Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Human Development and the Path to Freedom (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

17. Nicholas Crafts, “The Human Development Index, 1870–1999: Some Revised Estimates,” European Review of Economic History 6, no. 3 (2002): 395–405.

18. Azim F. Shariff, Dylan Wiwad, and Lara Beth Aknin, “Income Mobility Breeds Tolerance for Income Inequality: Cross-National and Experimental Evidence,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 11, no. 3 (2016): 373–80; Christina Starmans, Mark Sheskin, and Paul Bloom, “Why People Prefer Unequal Societies,” Nature Human Behaviour 1, no. 4 (2017): 1–7; Nick Cowen and Vincent Geloso, “Capital, Ideology, and the Liberal Order,” Analyse & Kritik 43, no. 2 (2021): 413–35; and Mikayla Novak, Inequality: an Entangled Political Economy Perspective (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

19. Jonathan Kelley and Mariah D. R. Evans, “Societal Inequality and Individual Subjective Well-Being: Results from 68 Societies and over 200,000 Individuals, 1981–2008,” Social Science Research 62 (2017): 1–23; and Krzysztof Zagorski, Jonathan Kelley, and Mariah D. R. Evans, “Economic Development and Happiness: Evidence from 32 Nations,” Polish Sociological Review 169 (2010): 3–19.

20. Alberto Alesina, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch, “Inequality and Happiness: Are Europeans and Americans Different?,” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9–10 (2004): 2009–42.

21. Finis Welch, “In Defense of Inequality,” American Economic Review 89, no. 2 (1999): 2.

22. Vadim Kufenko and Vincent Geloso, “Who Are the Champions? Inequality, Economic Freedom and the Olympics,” Journal of Institutional Economics 17, no. 3 (2021): 411–27; Christian Bjørnskov, Axel Dreher, Justina A.V. Fischer, Jan Schnellenbach, and Kai Gehring, “Inequality and Happiness: When Perceived Social Mobility and Economic Reality Do Not Match,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 91 (2013): 75–92; Christian Bjørnskov, “Growth, Inequality, and Economic Freedom: Evidence from the US States,” Contemporary Economic Policy 35, no. 3 (2017): 518–31; Daniel L. Bennett and Boris Nikolaev, “Economic Freedom & Happiness Inequality: Friends or Foes?,” Contemporary Economic Policy 35, no. 2 (2017): 373–91; and Vincent Geloso and James Dean, “Economic Freedom Improves Income Mobility: Evidence from Canadian Provinces,” Journal of Institutional Economics 1, no. 20 (2021): 1982–2018.

23. Robert C. Allen, “Absolute Poverty: When Necessity Displaces Desire,” American Economic Review 107, no. 12 (2017): 3690–721.

24. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “psychic income,” accessed April 11, 2023.

25. Alberto Alesina, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch, “Inequality and Happiness: Are Europeans and Americans Different?,” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9–10 (2004): 2009–2042; Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, “Happiness Inequality in the United States,” The Journal of Legal Studies 37, no. S2 (2008): S33–S79; Andrew E. Clark, Sarah Flèche, and Claudia Senik, “The Great Happiness Moderation: Well-Being Inequality during Episodes of Income Growth,” Happiness and Economic Growth: Lessons from Developing Countries (2014): 32–139; and Andrew E. Clark, Sarah Flèche, and Claudia Senik, “Economic Growth Evens Out Happiness: Evidence from Six Surveys,” Review of Income and Wealth 62, no. 3 (2016): 405–19.

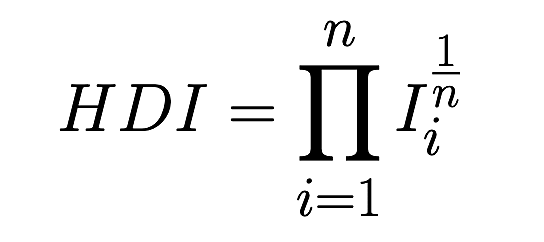

26. “Human Development Index (HDI),” United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports, accessed April 11, 2023.

27. Some series had to be spliced together. Contact the authors for the data supplementary files for a case-by-case documentation of our choices.

28. Some databases report countries differently. For example, some countries are reported in some databases as they are today even when they were formerly part of a larger polity (e.g., countries in the former Yugoslavia); others report only the larger polity until it split. To ensure consistency, when polities split or disappeared, we manually adjusted the values. This is most evident with the case of the USSR. Many of the satellites of the USSR reported no values in 1990 because they were part of the USSR unit in the data. As such, when the USSR dissolved, new polities had their own observations to report. Thus, as long as they were part of the USSR, we assigned these countries the USSR value. For example, take the food supply estimates for Kazakhstan and Belarus. Both countries are assigned the USSR values in 1990 and 1991 and their own values once they became separate entities.

29. “Life Expectancy at Birth, Total (years),” World Bank; “Mortality Rate, Infant (per 1,000 live births),” World Bank; “Food Supply (kcal per capita per day), ( –2013)” and “Food Supply (Kcal per capita per day), (2010– ),” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; “Death Rate from Air Pollution,” Our World in Data; Robert J. Barro and Jong-Wha Lee, “Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset,” Barro-Lee website, last updated September 2021; Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Sanden, “Maddison Style Estimates of the Evolution of the World Economy. A New 2020 Update,” Maddison Project Database, Version 2020, last modified May 22, 2022; note that the eighth component, “political freedom: democracy versus autocracy over time, scale 0 to 40,” is rescaled from the Polity5 Database, Center for Systemic Peace.

30. Infant mortality is inversely related to human progress—lower levels are better. This means that we had to transform the infant mortality rate into an infant survival rate.

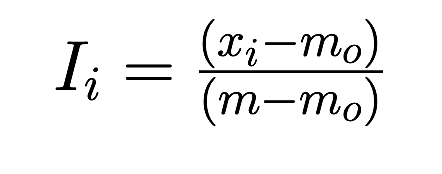

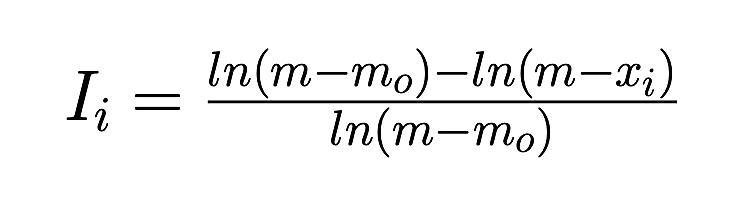

31. Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Human Development and the Path to Freedom (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022), p. 14.

32. Roderick Floud, Robert William Fogel, Bernard Harris, and Sok Chul Hong, The Changing Body: Health, Nutrition, and Human Development in the Western World since 1700 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 43.

33. We rescaled by adding 10 (which eliminates negative values) and scaling by 2 to avoid counting countries at 9 on the Polity5 as equally democratic as countries with a value of 10. By virtue of the properties of natural logs, countries with 10 cannot be computed (as it gives zero for the log, which cannot be defined). As such, countries with a 10 were given 1 on the index.

34. MLD is also referred to as generalized entropy of degree zero. See Frank Alan Cowell, “Generalized Entropy and the Measurement of Distributional Change,” European Economic Review 13, no. 1 (1980): 147–59. Note: Both measures were computed using the Stata package ineqdec0. See Stephen P. Jenkins, “INEQDEC0: Stata Module to Calculate Inequality Indices with Decomposition by Subgroup,” Boston College Department of Economics, 1999.

35. See Frank Alan Cowell and Emmanuel Flachaire, “Inequality Measures and the Median: Why Inequality Increased More Than We Thought,” Seventh Meeting of the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ), New York City, 2017.

36. “Data Downloads,” Human Development Reports, United Nations Development Programme.

37. Vincent Geloso, “Statogenic Climate Change? Julian Simon and Institutions,” Review of Austrian Economics 35 (2022): 1–16; Pierre Desrochers, Vincent Geloso, and Joanna Szurmak, “Care to Wager Again? An Appraisal of Paul Ehrlich’s Counterbet Offer to Julian Simon, Part 2: Critical Analysis,” Social Science Quarterly 102, no. 2 (2021): 808–29; and Leigh Raymond, “Economic Growth as Environmental Policy? Reconsidering the Environmental Kuznets Curve,” Journal of Public Policy 24, no. 3 (2004): 327–48.

38. “Child Mortality Rate, 2019,” Our World in Data, accessed April 11, 2023.

39. A mathematical example is useful here. Imagine a country with initial values of 0.4 on three different I that improves to 0.6 in only one of them. The equation would say that the HDI is 0.4579 after the improvement of 0.2 in that single indicator. However, if the improvement is split equally across all components (0.2/3), the resulting HDI is 0.4667.

40. It should be noted that variables that improve as their values fall require an additional transformation. For example, if the mortality rate is expressed per 1,000 persons, we transform it by subtracting the rate per 1,000 from 1,000. This essentially becomes a survival rate, which is easier to interpret in the logic of the HDI and HPI.

41. Nanak Kakwani, “Performance in Living Standards: An International Comparison,” Journal of Development Economics 41, no. 2 (1993): 307–36.