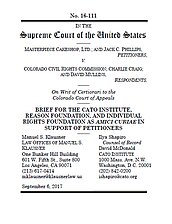

Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

While same-sex couples ought to be able to get marriage licenses—if the state is involved in marriage at all—a commitment to equality under the law can’t justify the restriction of private parties’ constitutionally protected rights like freedom of speech or association. Masterpiece Cakeshop, a bakery in Lakewood, Colorado, declined to bake a cake for the wedding of Charlie Craig and David Mullins. Jack Phillips, the shop’s owner, considers himself to be both an artist and a committed Christian whose faith permeates his art. Consistent with that faith, he will not create cakes marking events or ideas that violate his beliefs, such as cakes celebrating Halloween, incorporating hateful or vulgar messages, or celebrating any marriage that he believes is contrary to biblical teaching. While he refused to make the wedding cake, he did offer to make the couple any other cake they might like. Craig and Mullins responded by filing a charge of sexual orientation discrimination with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which found that Jack violated the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act and rejected his First Amendment defenses, saying that baking and decorating custom wedding cakes does not constitute artistic expression. The Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. Cato has filed an amicus brief supporting Masterpiece Cakeshop and urging the Court to vindicate Americans’ right not to speak. Although making cakes may not initially appear to be speech to some, it is a form of artistic expression and therefore constitutionally protected. There are numerous culinary schools throughout the world that teach students how to express themselves through their work; couples routinely spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars for the perfect cake designed specifically for them. Indeed, the Supreme Court has long recognized that the First Amendment protects artistic as well as verbal expression, and that protection should likewise extend to this sort of baking—even if it’s not ideological and even if done to make money. The Court declared nearly 75 years ago that “[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” W.Va. Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). And the Court ruled in Wooley v. Maynard—the 1977 “Live Free or Die” license-plate case out of New Hampshire—that forcing people to speak is just as unconstitutional as preventing or censoring speech. The First Amendment “includes both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all” and the Supreme Court has never held that the compelled-speech doctrine is only applicable when an individual is forced to serve as a courier for the message of another (as in Wooley). Instead, the justices have said repeatedly that what the First Amendment protects is a “freedom of the individual mind,” which the government violates whenever it tells a person what she must or must not say. Forcing a baker to create a unique piece of art violates that freedom of mind. Moreover, unlike true cases of public accommodation—the travelers’ inns at common law or the state-segregated restaurants in the Jim Crow South—there are abundant opportunities to choose other bakeries in the same area. Finally, granting First Amendment protection to bakers would not mean that public-accommodation laws could provide no protection to same-sex couples. The Free Speech Clause protects expression, which should include the custom design, baking, and decorating of wedding cakes, as well as photography and floristry, but not businesses like caterers, hotels, and limousine companies, who aren’t creating artistic expression. Those sorts of businesses may have other rights and legal defenses available, constitutional or statutory, but that’s a different matter.