Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

A bump stock is firearm accessory that allows the user to fire a semi-automatic gun more quickly by harnessing its recoil. After the tragic 2017 mass killing in Las Vegas, it was reported that the shooter used guns equipped with bump stocks to carry out his crime, leading to a backlash against the devices. Despite considerable bipartisan support in Congress for passing a bill banning bump stocks, President Trump told members of Congress not to address the issue. Instead, the president directed his administration to ban bump stocks by reinterpreting existing laws that ban fully automatic guns. Thus, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms reinterpreted the word “machinegun” to include bump-stock devices, despite a longstanding determination under both the Bush and Obama administrations that bump stocks did not fit within the legal meaning of “machinegun.”

As a result, possession of a bump stock is now a crime, even though Congress has never passed a law criminalizing the devices. Before the ban was enacted, members of the president’s own administration had expressed concerns about this approach, saying that only Congress has the power to ban bump stocks.

Several lawsuits were filed against the rule. In Guedes v. BATF, the D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of the government. Instead of analyzing whether the administration was correct in determining that the term “machinegun” includes bump stocks, however, the court simply deferred to the administration’s interpretation. This was an example of the controversial doctrine of “Chevron deference,” in which courts defer to an administrative agency’s permissible interpretation of a statutory term if the term is ambiguous.

Because of Chevron deference, the law often means whatever the current administration decides it should mean. And while the Supreme Court has told lower courts not to apply the doctrine to criminal laws, there is a grey area for laws like this that have both criminal and civil sides. So, even after both the challengers of the law and the administration asked the court not to apply Chevron deference, the D.C. Circuit did it anyways.

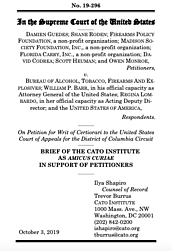

The plaintiffs in Guedes have petitioned the Supreme Court to hear their case and Cato has filed a brief in support. We argue that the Court should take the case and clarify that courts should not let the executive branch determine the meaning of the very laws they enforce, especially when the laws have criminal consequences. The structure of our Constitution is based around the principle of separation of powers, which is the idea that no single branch of government should exercise more than one of the three powers of government—legislative, executive, and judicial. It is Congress’s job to write the laws, the president’s job to enforce them, and the courts’ job to determine what they mean.

Chevron deference violates the Constitution’s structure by allowing the executive branch to rewrite the meaning of laws, cutting out the other two branches from the business of governing. This leads to bad law and bad politics by reducing both the accountability and stability of our legal system. Getting a bill passed through Congress is difficult by design — it encourages debate and compromise and protects our liberty. Short-circuiting that process is both unconstitutional and unwise. Without the Supreme Court’s intervention, American citizens will be punished for a crime that was crafted, interpreted, and enforced by executive branch bureaucrats without the input of their elected representatives or meaningful oversight by the courts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.