Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

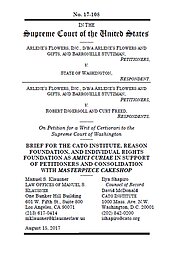

While same-sex couples ought to be able to get marriage licenses — if the state is involved in marriage at all — a commitment to equality under the law can’t justify the restriction of private parties’ constitutionally protected rights like freedom of speech or association. Arlene’s Flowers, a flower shop in Richland, Washington, declined to provide the floral arrangements for the wedding of Robert Ingersoll and Curt Freed. Mr. Ingersoll was a long-time customer of Arlene’s Flowers and the shop’s owner Barronelle Stutzman considered him a friend. But when he asked her to use her artistic abilities to beautify his ceremony, Mrs. Stutzman felt that her Christian convictions compelled her to decline. She gently explained why she could not do what he asked, and Mr. Ingersoll seemed to understand. Later, however, he and his now-husband, and ultimately the state of Washington, sued Mrs. Stutzman for violating the state’s laws prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations. The trial court ruled against Arlene’s Flowers on summary judgment. The Washington Supreme Court affirmed, holding that Mrs. Stutzman’s floral design did not constitute artistic expression worthy of First Amendment protection. Now the case is on the U.S. Supreme Court’s doorstep and Cato has filed an amicus brief supporting Arlene’s Flowers and Mrs. Stutzman, urging the Court to take up the case and consolidate it with Masterpiece Cakeshop, the case of the similarly situated Colorado baker that the Court has already agreed to hear. Although floristry may not initially appear to be speech to some, it’s a form of artistic expression that’s constitutionally protected. There are numerous floristry schools throughout the world that teach students how to express themselves through their work, and even the Arts Council of Great Britain has recognized the significance of the Royal Horticultural Society’s library, which documents the history, art, and writing of gardening. The U.S. Supreme Court has long recognized that the First Amendment protects artistic as well as verbal expression, and that protection should likewise extend to floristry — even if it’s not ideological and even if it’s done for commercial purposes. The Court declared more than 70 years ago that “[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” W.Va. Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). And the Court ruled in Wooley v. Maynard — the 1977 “Live Free or Die” license-plate case out of New Hampshire — that forcing people to speak is just as unconstitutional as preventing or censoring speech. The First Amendment “includes both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all” and the Supreme Court has never held that the compelled-speech doctrine is only applicable when an individual is forced to serve as a courier for the message of another (as in Wooley). Instead, the justices have said repeatedly that what the First Amendment protects is a “freedom of the individual mind,” which the government violates whenever it tells a person what she must or must not say. Forcing a florist to create a unique piece of art violates that freedom of mind. Moreover, unlike true cases of public accommodation, there are abundant opportunities to choose other florists in the same area. Finally, granting First Amendment protection to florists would not mean that public-accommodation laws could provide no protection to same-sex couples. The First Amendment protects expression, which should include floristry but would not include many other businesses like caterers, hotels, and limousine drivers who are not in the business of creating artistic expression. These sorts of businesses may have other defenses available, constitutional or statutory, but that’s a different legal matter.