On Jan. 23, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said that a “weaker dollar is good for trade.” On that, the greenback promptly made a three-year low. He uttered those remarks while addressing the annual gathering of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, of all places. The Swiss must have been amused to witness such a clueless remark by no less than a U.S. Treasury Secretary.

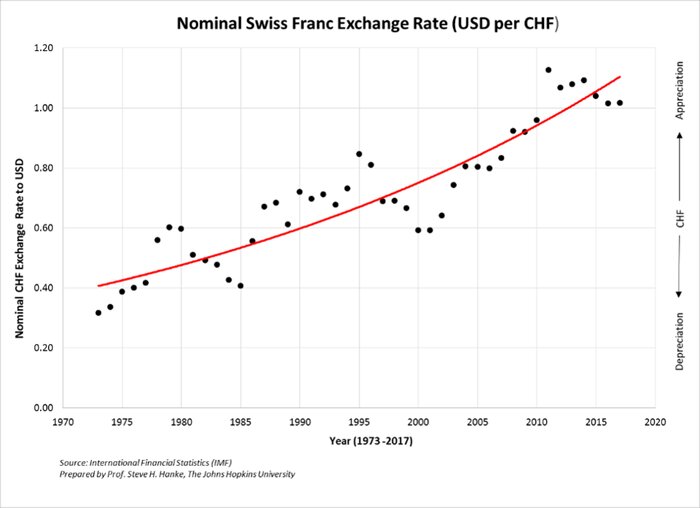

Switzerland has the world’s most competitive economy, according to the World Economic Forum's Global Competitive Index 2017-2018, and Switzerland didn’t arrive at the summit by devaluing the Swiss franc. Indeed, since the Bretton Woods system of pegged exchange rates collapsed in 1973 and exchange rates became “flexible,” the Swissie has been the world’s strongest currency. The chart below shows the appreciation of the franc against the greenback.

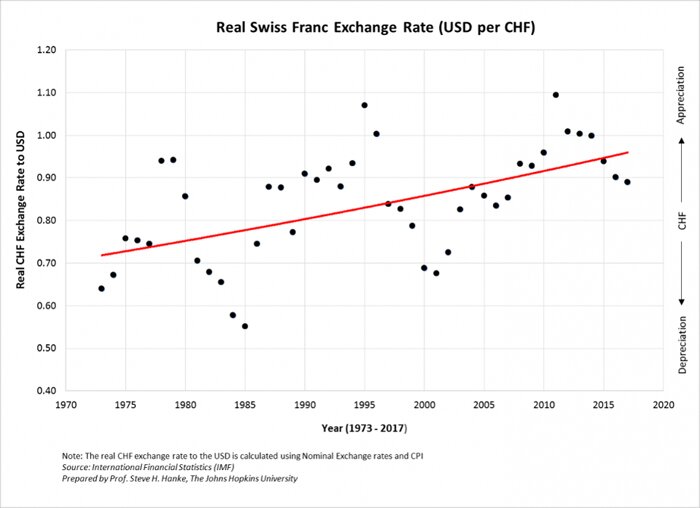

If we adjust the exchange rate for inflation differentials between Switzerland and the U.S. to determine a real exchange rate, the picture is the same. Namely, that the Swissie has appreciated against the greenback (see the chart below).

Just why does the evidence from Switzerland fly in the face of Secretary Mnuchin’s unfounded assertion? For those who study competitiveness and trade, the answer is clear. When businesses anticipate a “strong” domestic currency, they never become hooked on the phony notion that a “weak” currency will bail them out and somehow make them more competitive. No. Instead, they focus on their knitting and the quest for increasing the productivity of their businesses. Faced with the expectation of a strong currency, they know that the name of the “competitiveness game” is productivity.

Contrary to Secretary Mnuchin’s musings, an ever-appreciating currency is a sign of health and enhanced competitiveness. The evidence from Switzerland supports this, and so do data from a more broadly based sample of countries.

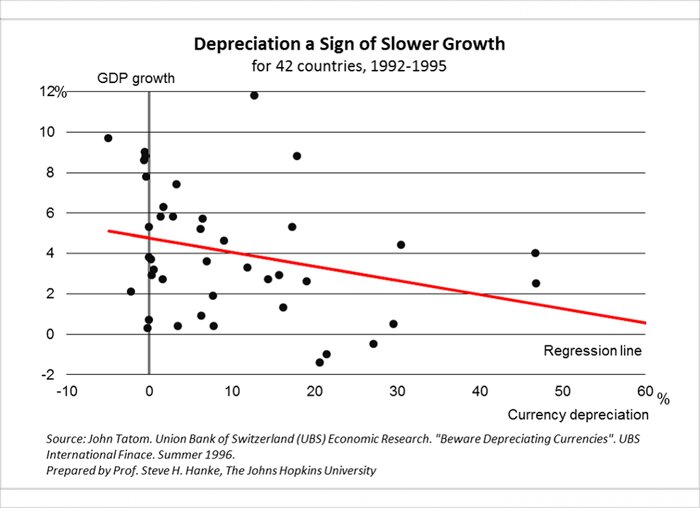

I recall the first time I met John “Jack” Tatom. It was in Zurich. At that time, Jack was the executive director and head of country research and limit control at Union Bank of Switzerland. Now, he is a fellow at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise, a research institute I founded with Prof. Louis Galambos in 1995.

One of the topics that Jack and I focused on over our lunch in Zurich was the widely held notion that devaluations are an economic elixir. He had just finished analyzing the relationship between average rates of currency depreciation against the U.S. dollar and real GDP growth for 42 countries in the 1992-95 period. These countries included the four Asian Tigers and selected emerging countries in Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa.

As the chart below shows, the evidence fails to support the idea that currency depreciations boost growth. Indeed, he found just the opposite: Currency appreciations are associated with stronger growth.

The data speak loudly. Secretary Mnuchin, are you listening?