On June 23rd, the voters in the United Kingdom (UK) turned a collective thumbs-down on the European Union (EU). The Brexit advocates won the day, shocking the establishment and temporarily unsettling the markets. It also poured fuel on a simmering Italian fire — a fire that could result in an Italian, as well as a Eurozone, doomsday scenario.

The results of stress tests for European banks (reported on July 29th) showed that Italy’s Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) was the only European bank (of the 51 tested) to have its capital wiped out in the stress test scenario. Following the release of those results, Monte Paschi announced it would raise capital by issuing stock, and the Italian treasury indicated that there would not be a bailout of Italian banks. In addition, Fabrizio Viola, MPS’s CEO, got the axe and was replaced by Marco Morelli. So, the stage is set to raise €5 billion in new capital and dispose of about €30 billion in non-performing loans at MPS.

But, storm clouds remain on the horizon. MPS has already burnt through €12 billion of capital raised since 2008. Why won’t it burn through another €5 billion? Also, there are questions about the ability to raise new bank capital in Italy — where banks are loaded with non-performing loans (approximately €200 billion) and their shares are trading below book value.

If the new private capital for MPS is not raised, and raised post-haste, Italy and the EU will butt heads, and therein lies the potential for a storm. Without new capital, MPS’s bondholders would be forced to take losses (a bail-in) before any government bailout money can be deployed under EU rules. But, a “bail-in” would be political suicide for Prime Minister Renzi because retail investors hold a big chunk of Italian bank debt (bonds). These retail investors vote in large numbers and, suffering losses from a bail-in, bondholders would probably vote in the October referendum against Renzi’s proposed changes to Italy’s constitution. Such an outcome would probably force Renzi out and open the door for the populist Five Star Movement. So, the Italian political landscape looks unsettled.

What about the economy? A look at the economy requires a model of economic activity. The monetary approach posits that changes in the money supply, broadly determined, cause changes in nominal national income and the price level. Sure enough, the growth of broad money and nominal GDP are closely linked.

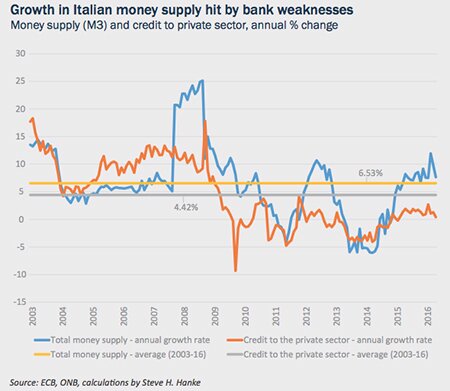

Italy’s money supply (M3) growth rate since 2010 has been well below its trend rate (6.53 percent) for most of the period (see the accompanying chart). Not surprisingly, Italy’s nominal GDP growth rate during the 2010-2015 period was only 0.4 percent per year.

If we break down the contribution to the money supply growth, only 17 percent of Italy’s M3 is accounted for by State money produced by the European Central Bank (ECB). The remaining 83 percent is Bank money produced by commercial banks through deposit creation. So, Italy’s banks are an important contributor to the money supply and the economy. However, recently, banks have been struggling and anything that would cause their loan books to contract — which would cause the money supply and credit to the private sector in Italy to slow down — would plunge Italy into another recession.

Monte Paschi is not the only problem child. All of Italy’s big banks could use some additional capital, but issuing new shares is unattractive because their shares are trading below book value (Intesa Sanpaolo’s P/B is 0.77; UniCredit is 0.27; UBI Banca is 0.24; Banco Popolare is 0.22; and Monte Paschi is 0.07).

Without new private capital, an Italian state rescue is the most attractive source for the recapitalization. Otherwise, the Italian banks will be bailed-in by the bondholders, Renzi’s constitutional changes will go down in flames, and Renzi’s government will collapse. With that, the Five Star Movement will probably form a government, and Italy will exit the Eurozone. So, if the EU does not bend and allow one of the loopholes in its rules to be used, the Boys in Brussels could set a doomsday machine into motion.