Just one week after raising their target interest rate, Fed officials assured the public the fight to get inflation down is not over. They even doubled down on their efforts to convince everyone they’re still committed to a 2 percent inflation target.

Even better, the latest inflation figures remain headed in the right direction. The month-to-month changes in the CPI and the PCE, as well as in the “core” versions of those indexes, have been trending lower for (at least) a few months.

It is true that the year-to-year inflation figures remain elevated. But as I demonstrated in September (and October), even if monthly inflation remains flat through August 2023, the annual inflation rate won’t drop below 3 percent until May 2023. It’s just the math–the year-to-year changes will remain above average because the initial spike was so high. (It’s also true that egg prices are elevated, but that’s not inflation.)

That’s the good news.

The not-so-good news is the Fed refuses to give up on an outdated model of the economy. I refer, of course, to the dreaded Phillips curve, the supposed inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. (The Phillips curve is the zombie of the economics profession–it died, but it still roams the earth, mainly in the metro Washington DC/Northeastern corridor.)

Its effects are noxious. As the Washington Post reports, “the labor market is still piping hot, complicating the Fed’s fight to lower prices and tame inflation that stems from rising wages and mismatches in the labor market.” In reality, though, rising unemployment is not a necessary evil for getting rid of inflation, and economic growth does not automatically produce inflation. A ton of negative experience and evidence now exists against the Phillips curve but it doesn’t seem to matter.

And even if a strong Phillips curve relationship did exist, experience casts severe doubt on whether a central bank could exploit the relationship. The latest exhibit is currently on full display. According to Chair Powell, the Fed “didn’t expect” the labor market to be so strong, and Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari claims that he “too was surprised by the big jobs number.”

Everyone should appreciate the candor, but the fact that the Fed can’t let go of the Phillips curve and can’t forecast employment doesn’t inspire a great deal of confidence.

The really bad news, though, is that people shouldn’t have too much confidence in modern monetary policy at all. There’s more than enough empirical evidence to reconsider whether the Fed has contributed positively to economic stabilization, even if we ignore the Great Depression and the Great Recession.

Skeptical? Check out this NBER paper that summarizes both the theory and evidence for exactly how monetary policy is supposed to affect the economy. (The econ term is the monetary policy transmission mechanism.) The paper was published in 2010, but the conclusions have not radically changed. According to the authors:

Monetary policy innovations have a more muted effect on real activity and inflation in recent decades as compared to the effects before 1980. Our analysis suggests that these shifts are accounted for by changes in policy behavior and the effect of these changes on expectations, leaving little role for changes in underlying private-sector behavior (outside shifts related to monetary policy changes).

In a nutshell: There’s a lack of easily identifiable effects on private sector behavior from monetary policy, particularly after 1980. (Put differently, “the responses of measures of real activity and prices have become smaller and more persistent since 1984.”)

So even aside from the evidence against the Phillips curve, nobody should be super shocked to hear Kashkari admit that, so far, he is “not seeing much of an imprint of our tightening to date on the labor market.” But there are other pieces to this story that many folks might find surprising.

First, believe it or not, there is some controversy over precisely how much the Fed influences market interest rates through monetary policy. My read of the evidence is, broadly speaking, far less than everyone seems to think. (There’s also a long history that clearly demonstrates, at best, lack of precise control over even the federal funds rate, much less other short-term rates.) Regardless, the Fed tends to follow changes in market rates.

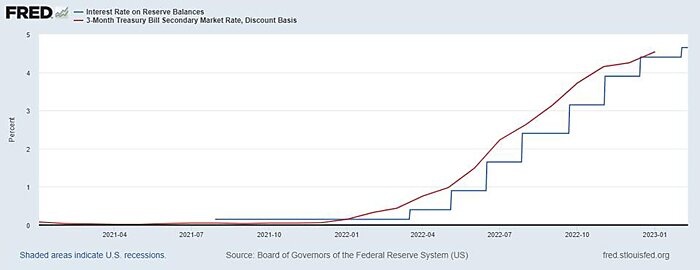

This relationship can be seen in the lead up to the 2008 crisis, and in its aftermath. It’s also in the 2022 data, when the Fed started its rate-raising campaign. (The graph below uses a three-month Treasury rate, but other short-term market rates work as well.)

Now, I’ll be the first to admit that the Fed could have a major negative effect on short-term market interest rates if it chose to do so. The Fed could, for instance, raise reserve requirements while rapidly selling large quantities of its assets. This action would remove a massive amount of liquidity from the market. But that’s exactly why the Fed isn’t about to do it.

Like it or not, the Fed is the lender of last resort (I.E., the ultimate source of liquidity) and it’s charged with stamping out risks to financial stability. It isn’t about to purposely make liquidity incredibly scarce.

Finally, it is not entirely clear that credit markets, broadly, have become particularly tight as rates have ratcheted up. While it is difficult to measure just how tight credit markets have become, at least one Fed metric suggests they’re not particularly tight and that conditions have been easing since October 2022. (Commercial banks have been lending more through the Fed’s tightening cycle, and according to SIFMA data, repo market volume is up in 2022. But these types of metrics describe only narrow pieces of financial markets.)

At the macro level, retail sales have been mostly growing since 2020, and both gross domestic private investment and net domestic investment by private businesses have basically trended up since 2021. Industrial production has been on a generally upward trend (though it did decline from October through December), and GDP has barely missed a beat.

If the Fed really has been trying to “slow down the economy,” it hasn’t done it. Yet, inflation has been falling.

Obviously, it’s important to figure out exactly why inflation spiked in the first place, and why it is falling. My money is on stimulative fiscal policy worsening the effects of COVID shutdowns, not monetary policy. And the Fed accommodated that fiscal burst.

Speaking of which, we have an even bigger problem than in years past because the Fed can now accommodate fiscal policy more easily than before. That is, the Fed can now purchase financial assets without creating the types of inflationary pressures that those purchases would have created prior to 2008.

Congress can address this problem by imposing a cap on the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and on the portion of outstanding U.S. debt the Fed can hold. Longer-term, though, it’s time for Congress to ditch the current system precisely because it depends on a central bank to “speed up the economy” to stave off deflation and to “slow down the economy” to fight inflation.

A better alternative would be to narrow the Fed’s legislative mandate while leveling the regulatory playing field between the U.S. dollar and other potential means of payment. There are many good reasons the Fed should not be targeting prices, and allowing competitive private markets to provide currency would present a powerful a check on the government’s ability to diminish the quality of money.