Congress should

• abolish the U.S. Agency for International Development and end government-to-government aid programs;

• withdraw from the World Bank and regional multilateral development banks;

• not use foreign aid to encourage or reward market reforms in the developing world;

• eliminate programs that provide loans to the private sector in developing countries and oppose schemes that guarantee private-sector investments abroad;

• privatize or abolish the Export-Import Bank, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, and other sources of international corporate welfare; and

• end government support of microenterprise lending and nongovernmental organizations.

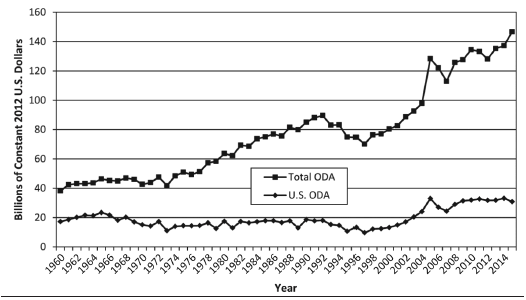

Foreign aid has risen notably since the turn of this century. The United States spends $31 billion in overseas development assistance, and total aid from rich countries is now around $147 billion per year (see Figure 80.1).

Despite that increase in foreign aid, what we know about aid and development provides little reason for enthusiasm:

• There is no correlation between aid and growth.

• Aid that goes into a poor policy environment doesn't work and contributes to debt.

• Aid conditioned on market reforms has failed.

Figure 80.1

Official Development Assistance, 1960–2015

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, http://data.oecd.org/oda/net-oda.htm.

• Countries that have adopted market-oriented policies have done so because of factors unrelated to aid.

• There is a strong relationship between economic freedom and growth.

A widespread consensus has formed about those points, even among development experts who have long supported government-to-government aid. The increase in aid reflects a gap between the scholarly consensus on the limits of development assistance and the political push that has made more spending happen.

The Dismal Record of Foreign Aid

By the 1990s, the failure of conventional government-to-government aid schemes had been widely recognized and brought the entire foreign assistance process under scrutiny. For example, a Clinton administration task force conceded that "despite decades of foreign assistance, most of Africa and parts of Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East are economically worse off today than they were 20 years ago." As early as 1989, a bipartisan task force of the House Foreign Affairs Committee concluded that U.S. aid programs "no longer either advance U.S. interests abroad or promote economic development."

Multilateral aid has also played a prominent role in the post–World War II period. The World Bank, to which the United States is the major contributor, was created in 1944 to provide aid mostly for infrastructure projects in countries that could not attract private capital on their own. The World Bank has since expanded its lending functions, as have the regional development banks that have subsequently been created on the World Bank's model and to which the United States contributes: the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), also established in 1944, long ago abandoned its original role of maintaining exchange-rate stability around the world and has since engaged in long-term lending on concessional terms to most of the same clients as the World Bank.

Despite record levels of lending, the multilateral development banks have not achieved any more success at promoting economic growth than has the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Numerous self-evaluations of World Bank performance over the years, for example, have uncovered high failure rates of bank-financed projects. In 2000, the bipartisan congressional Meltzer Commission found a 55 to 60 percent failure rate of World Bank projects based on the bank's own evaluations. A 1998 World Bank report concluded that aid agencies "saw themselves as being primarily in the business of dishing out money, so it is not surprising that much [aid] went into poorly managed economies — with little result." The report also said that foreign aid had often been "an unmitigated failure." "No one who has seen the evidence on aid effectiveness," commented Oxford University economist Paul Collier in 1997, "can honestly say that aid is currently achieving its objective."

There are several reasons that massive transfers from the developed to the developing world have not led to a corresponding transfer of prosperity. Aid has traditionally been lent to governments, has supported central planning, and has been based on a fundamentally flawed vision of development.

By lending to governments, USAID and the multilateral development agencies supported by Washington have helped expand the state sector at the expense of the private sector in poor countries. U.S. aid to India from 1961 to 1989, for example, amounted to well over $2 billion, almost all of which went to the Indian state. Moreover, much aid goes to autocratic governments.

Foreign aid has thus financed governments, both authoritarian and democratic, whose policies have been the principal cause of their countries' impoverishment. Trade protectionism, byzantine licensing schemes, inflationary monetary policy, price and wage controls, nationalization of industries, exchange-rate controls, state-run agricultural marketing boards, and restrictions on foreign and domestic investment, for example, have all been supported explicitly or implicitly by U.S. foreign aid programs.

Not only has lack of economic freedom kept literally billions of people in poverty, but development planning has thoroughly politicized the economies of developing countries. Centralization of economic decisionmaking in the hands of political authorities has meant that a substantial amount of poor countries' otherwise useful resources has been diverted to unproductive activities, such as rent seeking by private interests or politically motivated spending by the state.

Precisely because aid operates within the (usually deficient) political and institutional environments of recipient countries, even when it goes to countries that don't rely on development planning, it can have detrimental effects. That is all the more true with higher levels of foreign assistance, as has been the case with Sub-Saharan African countries, most of which have received 10 percent or more of their national income in foreign aid for at least three decades. As Nobel laureate in economics Angus Deaton notes, "large inflows of foreign aid change local politics for the worse and undercut the institutions needed to foster long-run growth. Aid also undermines democracy and civic participation, a direct loss over and above the losses that come from undermining economic development."

It has become abundantly clear that, as long as the conditions for economic growth do not exist in developing countries, no amount of foreign aid will be able to produce economic growth. Indeed, a comprehensive study by the IMF found no relationship between aid and growth. Moreover, economic growth in poor countries does not depend on official transfers from outside sources. Were that not so, no country on earth could ever have escaped from initial poverty. The long-held premise of foreign assistance — that poor countries were poor because they lacked capital — not only ignored thousands of years of economic development history, it also was contradicted by contemporary events in the developing world, which saw the accumulation of massive debt, not development.

Promotion of Market Reforms

Even aid intended to advance market liberalization can produce undesirable results. Such aid takes the pressure off recipient governments and allows them to postpone, rather than promote, necessary but politically difficult reforms. Ernest Preeg, former chief economist at USAID, for instance, saw that problem in the Philippines after the collapse of the Marcos dictatorship: "As large amounts of aid flowed to the Aquino government from the United States and other donors, the urgency for reform dissipated. Economic aid became a cushion for postponing difficult internal decisions on reform. A central policy focus of the Aquino government became that of obtaining more and more aid rather than prompt implementation of the reform program."

Far more effective at promoting market reforms is the suspension or elimination of aid. Although USAID lists South Korea and Taiwan as success stories of U.S. economic assistance, those countries began to take off economically only after massive U.S. aid was cut off. As even the World Bank has conceded, "Reform is more likely to be preceded by a decline in aid than an increase in aid."

Still, much aid is delivered on the condition that recipient countries implement market-oriented economic policies. Such conditionality is the basis for the World Bank's structural adjustment lending, which it began in the early 1980s after it realized that pouring money into unsound economies would not lead to self-sustaining growth. But aid conditioned on reform has been ineffective at inducing reform. One 1997 World Bank study noted that there "is no systematic effect of aid on policy." A 2002 World Bank study admitted that "too often, governments receiving aid were not truly committed to reforms" and that "the Bank has often been overly optimistic about the prospects for reform, thereby contributing to misallocation of aid." Oxford's Paul Collier explains: "Some governments have chosen to reform, others to regress, but these choices appear to have been largely independent of the aid relationship. The microevidence of this result has been accumulating for some years. It has been suppressed by an unholy alliance of the donors and their critics. Obviously, the donors did not wish to admit that their conditionality was a charade."

Lending agencies have an institutional bias toward continued lending even if market reforms are not adequately introduced. Yale University economist Gustav Ranis explains that within some lending agencies, "ultimately the need to lend will overcome the need to ensure that those [loan] conditions are indeed met." In the worst cases, of course, lending agencies do suspend loans in an effort to encourage reforms. When those reforms begin or are promised, however, the agencies predictably respond by resuming the loans — a process Ranis has referred to as a "time-consuming and expensive ritual dance."

In sum, aiding reforming nations, however superficially appealing, does not produce rapid and widespread liberalization. Just as Congress should reject funding for regimes that are uninterested in reform, it should reject schemes that call for funding countries on the basis of their records of reform. This includes the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a U.S. aid agency created in 2004 to direct funds to poor countries with sound policy environments. The most obvious problem with that program is that it is based on a conceptual flaw: countries that are implementing the right policies for growth, and therefore do not need foreign aid, will be receiving aid. In practice, the effectiveness of such selective aid has been questioned by a recent IMF review that found "no evidence that aid works better in better policy or geographical environments, or that certain forms of aid work better than others."

The practical problems are indeed formidable. The Millennium Challenge Corporation and other programs of its kind require government officials and aid agencies — all of which have a poor record in determining when and where to disburse foreign aid — to make complex judgment calls on which countries deserve the aid and when. Moreover, it is difficult to believe that bureaucratic self-interest, micromanagement by Congress, and other political or geostrategic considerations will not continue to play a role in the disbursement of this kind of foreign aid. It is important to remember that the creation of the Millennium Challenge Corporation was not an attempt to reform U.S. foreign aid. Rather, the aid funds it administers are in addition to the much larger traditional aid programs that will continue to be run by USAID — in many cases in the very same countries.

Help for the Private Sector

Enterprise funds are another initiative intended to help market economies. Under this approach, the U.S. government, typically through USAID, has established and financed venture funds throughout the developing world. The purpose is to promote economic progress and "jump start" the market by investing in the private sector. Some of them have expired, some still exist, and others are being proposed.

It was never clear exactly how such government-supported funds find profitable private ventures in which the private sector is unwilling to invest. Numerous evaluations have found that most enterprise funds have lost money, and many have simply displaced private investment that otherwise would have occurred. Moreover, there is no evidence that the funds have generated additional private investment, had a positive effect on development, or helped create a better investment environment in poor countries.

Similar efforts to underwrite private entrepreneurs are evident at the World Bank (through its program to guarantee private-sector investment) and at U.S. agencies such as the Export-Import Bank, Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the Trade and Development Agency, which provide comparable services. U.S. officials justify the programs on the grounds that they help promote development and benefit the U.S. economy. Yet providing loan guarantees and subsidized insurance to the private sector relieves the governments of underdeveloped countries of the need to create an investment environment that would attract foreign capital on its own. To attract much-needed investment, countries should establish secure property rights and sound economic policies, rather than rely on Washington-backed schemes that allow avoidance of those reforms.

Moreover, while some corporations clearly benefit from the array of foreign assistance schemes, the U.S. economy and American taxpayers do not. Subsidized loans and insurance programs amount to corporate welfare. Macroeconomic policies and conditions, not corporate welfare programs, affect factors such as the unemployment rate and the size of the trade deficit. Programs that benefit specific interest groups manage only to rearrange resources within the U.S. economy and do so in a very wasteful manner. Indeed, the United States did not achieve and does not maintain its status as the world's largest exporter because of agencies like the Export-Import Bank, which finances less than 2 percent of U.S. exports.

Even USAID has claimed that the main beneficiary of its lending is the United States because close to 80 percent of its contracts and grants go to American firms. That argument is fallacious. "To argue that aid helps the domestic economy," renowned economist Peter Bauer explained, "is like saying that a shop-keeper benefits from having his cash register burgled so long as the burglar spends part of the proceeds in his shop."

Debt Relief

By the mid-1990s, dozens of countries suffered from inordinately high foreign debt levels. Thus, the World Bank and the IMF devised a $75 billion debt-relief initiative benefiting 39 heavily indebted poor countries. The initiative, of course, is an implicit recognition of the failure of past lending to produce self-sustaining growth, especially since an overwhelming percentage of eligible countries' public foreign debt is owed to bilateral and multilateral lending agencies. Indeed, in 2006, at about the time the debt relief initiative began taking effect, 96 percent of those countries' long-term debt was public or publicly guaranteed.

Forgiving poor nations' debt is a sound idea, on the condition that no other aid is forthcoming. Unfortunately, the multilateral debt initiative promises to keep poor countries on a borrowing treadmill, since they will be eligible for future multilateral loans based on conditionality. There is no reason, however, to believe that conditionality will work any better in the future than it has in the past. Again, as a World Bank study emphasized, "A conditioned loan is no guarantee that reforms will be carried out — or last once they are."

Nor is there reason to believe that debt relief will work better now than in the past. As former World Bank economist William Easterly has documented, donor nations have been forgiving poor countries' debts since the late 1970s, and the result has simply been more debt. From 1989 to 1997, 41 highly indebted countries saw some $33 billion of debt forgiveness, yet they still found themselves in an untenable position by the time the current round of debt forgiveness began. Indeed, they have been borrowing ever-larger amounts from aid agencies. Easterly notes, moreover, that private credit to the heavily indebted poor countries has been virtually replaced by foreign aid and that foreign aid itself has been lent on increasingly easier terms.

The debt relief initiative has in fact reduced debt, but only time will tell whether this latest round of forgiveness will be yet another failed attempt to resolve poor countries' debt. Unfortunately, there are already worrying signs. For example, debt owed to official and private creditors has been rising steadily again in African countries that made up the bulk of the heavily indebted poor countries initiative. The public debt of Sub-Saharan African countries is now 35 percent of gross domestic product, up from 27 percent just four years earlier.

Other Initiatives

The inadequacy of government-to-government aid programs has prompted an increased reliance on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). NGOs, or private voluntary organizations (PVOs), are said to be more effective at delivering aid and accomplishing development objectives because they are less bureaucratic and more in touch with the on-the-ground realities of their clients.

Although channeling official aid monies through PVOs has been referred to as a "privatized" form of foreign assistance, it is often difficult to make a sharp distinction between government agencies and PVOs beyond the fact that the latter are subject to less oversight and are less accountable. Michael Maren, a former employee at Catholic Relief Services and USAID, notes that most PVOs receive most of their funds from government sources.

Given that relationship — PVO dependence on government hardly makes them private or voluntary — Maren and others have described how the charitable goals on which PVOs are founded have been undermined. The nonprofit organization Development GAP, for example, observed that USAID's "overfunding of a number of groups has taxed their management capabilities, changed their institutional style, and made them more bureaucratic and unresponsive to the expressed needs of the poor overseas." Maren adds, "When aid bureaucracies evaluate the work of NGOs, they have no incentive to criticize them." For their part, NGOs naturally have an incentive to keep official funds flowing. The lack of proper impact assessments plagues the entire foreign aid establishment, prompting former USAID head Andrew Natsios to acknowledge, "We don't get an objective analysis of what is really going on, whether the programs are working or not." In the final analysis, government provision of foreign assistance through PVOs instead of traditional channels does not produce dramatically different results.

Microenterprise lending, another increasingly popular program among advocates of aid, is designed to provide small amounts of credit to the world's poorest people. The poor use the loans to establish livestock, manufacturing, and trade enterprises, for example. Many microloan programs, such as the one run by the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, appear to be highly successful. Grameen has disbursed almost $20 billion since the 1970s and achieved a repayment rate of about 97 percent according to its founder. Microenterprise lending institutions, moreover, are intended to be economically viable, to achieve financial self-sufficiency within three to seven years.

Given those qualities, it is unclear why microlending organizations would require subsidies. Indeed, microenterprise banks typically refer to themselves as profitable enterprises. For those and other reasons, Jonathan Morduch of New York University concluded in a 1999 study that "the greatest promise of microfinance is so far unmet, and the boldest claims do not withstand close scrutiny." He added that, according to some estimates, "if subsidies are pulled and costs cannot be reduced, as many as 95 percent of current programs will eventually have to close shop." More recently, David Roodman of the Center for Global Development found little evidence for the grand claims of the microcredit movement, including that it can noticeably reduce poverty. He advocated reducing funding for microlending and increasing its effectiveness.

Furthermore, microenterprise programs alleviate the conditions of the poor, but they do not address the causes of the lack of credit faced by the poor. In developing countries, for example, about 90 percent of poor people's property is not recognized by the state. Without secure private property rights, most of the world's poor cannot use collateral to obtain a loan. The Institute for Liberty and Democracy, a Peruvian think tank, found that, when poor people's property in Peru was registered, new businesses were created, production increased, asset values rose by 200 percent, and credit became available. Of course, the scarcity of credit is also caused by a host of other policy measures, such as financial regulation that makes it prohibitively expensive to provide banking services for the poor.

In sum, microenterprise programs can be beneficial, but successful programs need not receive aid subsidies. The success of microenterprise programs, moreover, will depend on specific conditions, which vary greatly from country to country. For that reason, microenterprise projects should be financed privately by people who have their own money at stake rather than by international aid bureaucracies that appear intent on replicating such projects throughout the developing world.

Conclusion

Numerous studies have found that economic growth is strongly related to the level of economic freedom. Put simply, the greater a country's economic freedom, the greater its level of prosperity over time (Figure 80.2). Likewise, the greater a country's economic freedom, the faster it will grow. Economic freedom — which includes not only policies, such as free trade and stable money, but also institutions, such as the rule of law and the security of private property rights — increases more than just income. It is also strongly related to improvements in other development indicators such as longevity, access to safe drinking water, lower corruption, and dramatically higher incomes for the poorest members of society (Figure 80.3).

The developing countries that have most liberalized their economies and achieved high levels of growth have done far more to reduce poverty and improve their citizens' standards of living than have foreign aid programs. As Deaton observes:

Figure 80.2

Economic Freedom and Income per Capita, 2013

SOURCE: James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, and Joshua Hall, Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2015), p. 23.

NOTE: GDP = gross domestic product; PPP = purchasing power parity.

Even in good environments, aid compromises institutions, it contaminates local politics, and it undermines democracy. If poverty and underdevelopment are primarily consequences of poor institutions, then by weakening those institutions or stunting their development, large aid flows do exactly the opposite of what they are intended to do. It is hardly surprising then that, in spite of the direct effects of aid that are often positive, the record of aid shows no evidence of any overall beneficial effect.

In the end, a country's progress depends almost entirely on its domestic policies and institutions, not on outside factors such as foreign aid. As Easterly suggests, aid distracts from what really matters, "such as the role of political and economic freedom in achieving development." Congress should recognize that foreign aid has not caused the worldwide shift toward the market and that appeals for more foreign aid, even when intended to promote the market, will continue to do more harm than good.

Figure 80.3

Economic Freedom and Income Level of Poorest 10 Percent, 2013

SOURCE: Gwartney James, Robert Lawson, and Joshua Hall, Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2015), p. 23.

NOTE: PPP = purchasing power parity.

Suggested Readings

Anderson, Robert E. Just Get Out of the Way: How Government Can Help Business in Poor Countries. Washington: Cato Institute, 2004.

Bandow, Doug, and Ian Vásquez, eds. Perpetuating Poverty: The World Bank, the IMF, and the Developing World. Washington: Cato Institute, 1994.

Bauer, P. T. Dissent on Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Deaton, Angus. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

De Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Dichter, Thomas. "A Second Look at Microfinance: The Sequence of Growth and Credit in Economic History." Cato Institute Development Briefing Paper no. 1, February 15, 2007.

Djankov, Simeon, Jose Montalvo, and Marta Reynal-Querol. "Does Foreign Aid Help?" Cato Journal 26, no. 1 (Winter 2006).

Easterly, William. "Freedom versus Collectivism in Foreign Aid." In Economic Freedom of the World: 2006 Annual Report, edited by James Gwartney and Robert Lawson. Vancouver, British Columbia: Fraser Institute, 2006, pp. 29-41.

---. The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. New York: Basic Books, 2013.

---. The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

Erixon, Fredrik. Aid and Development: Will It Work This Time? London: International Policy Network, 2005.

Gwartney, James, Robert Lawson, and Joshua Hall. Economic Freedom of the World: 2016 Annual Report. Vancouver, British Columbia: Fraser Institute, 2016.

International Financial Institution Advisory Commission (Meltzer Commission). "Report to the U.S. Congress and the Department of the Treasury." March 8, 2000.

Lal, Deepak. The Poverty of "Development Economics." London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1983, 1997.

Maren, Michael. The Road to Hell: Foreign Aid and International Charity. New York: Free Press, 1997.

Munk, Nina. The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty. New York: Anchor Books, 2013.

Roodman, David. Due Diligence: An Impertinent Inquiry into Microfinance. Baltimore, MD: Brookings Institution Press, 2012.

Vásquez, Ian. "Commentary." In Making Aid Work, by Abhijit Banerjee. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007, pp. 47-53.

---. "The Asian Crisis: Why the IMF Should Not Intervene." Vital Speeches, April 15, 1998.

---. "The New Approach to Foreign Aid: Is the Enthusiasm Warranted?" Cato Institute Foreign Policy Briefing no. 79, September 17, 2003.

Vásquez, Ian, and John Welborn. "Reauthorize or Retire the Overseas Private Investment Corporation?" Cato Institute Foreign Policy Briefing no. 78, September 15, 2003.