Policymakers should

• reject calls for protectionist economic policies, especially those that would negatively affect bilateral trade with China;

• move away from trying to preserve U.S. military primacy in East Asia and adopt a more restrained, modest strategy that does not seek to contain China;

• insist on maintaining freedom of navigation in the South China Sea while maintaining a policy of neutrality regarding territorial disputes;

• continue to sell weapons to Taiwan and provide economic support for the island, but end the implicit, increasingly risky defense commitment to the island;

• prevent competition in cyberspace from escalating into kinetic conflict; and

• clarify the U.S.– Japan defense treaty so that the United States does not have an obligation to defend the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands against China.

The U.S.-China relationship features both cooperation and competition — though the latter has come to characterize the relationship to a much greater extent in the last year. With increasing regularity, Washington and Beijing have discovered where their interests diverge, since most of the "low-hanging fruits" of cooperation have already been exploited. Cooperation in the fields of environmental protection, reining in North Korea, and trade should be praised and encouraged. But sources of friction in the relationship, such as territorial disputes in the South China Sea and acts of Chinese cyber espionage against U.S. companies, require careful management by American policymakers.

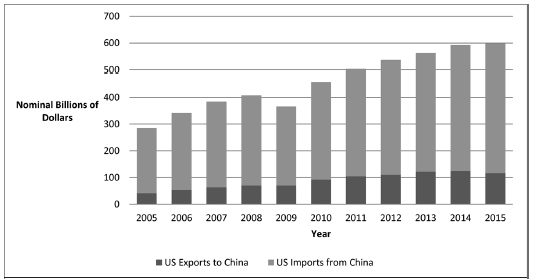

Figure 71.1

U.S.-China Trade in Goods, 2005–2015

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

Policymakers in Washington must look beyond inflammatory rhetoric and calls for trade policies that would exacerbate the negative aspects of the U.S.-China relationship for little benefit. For example, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, total bilateral trade in goods for 2015 was valued at $599.3 billion: the United States exported $116.1 billion to China while importing $483.2 billion from China (see Figure 71.1). Disrupting this trade flow would be detrimental to both countries. Policymakers need to resist the growing populist calls for protectionist trade policies.

Given the scale and complexity of the U.S.-China relationship, a full accounting in this chapter is not feasible. Instead, this chapter will examine three major sources of friction in the relationship — territorial disputes with American allies, cyber espionage against U.S. companies, and America's grand strategy of primacy — and offer recommendations for U.S. policymakers to ease tensions. Figuring out ways to effectively manage these sources of friction will greatly benefit the U.S.-China relationship.

Territorial Disputes with U.S. Allies

The most serious source of friction in the U.S.-China relationship is territorial disputes between China and American allies. Beijing has made significant investments in its armed forces, acquiring advanced warships, missile systems, and aircraft and steadily improving the quality of military training. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, China's official defense budget, which is widely considered to be lower than actual military spending, increased from $29.5 billion in 2005 to $146 billion in 2015. The dispute in the South China Sea has dominated recent headlines, but unresolved disputes between China and Japan in the East China Sea and a long-standing conflict between China and Taiwan could easily flare up in the near future.

Recently, the South China Sea has been the most active of the three conflict areas. Beijing's island-building campaign has added more than 3,200 acres of land to the seven "maritime features" that China occupies in the Spratly archipelago. Many of China's artificial islands include runways that can accommodate military aircraft, thereby threatening the security of other claimants, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, and vital international shipping lanes. In addition to island building, Beijing has made sweeping claims to the South China Sea that the United States considers to be in violation of international law. In response, the U.S. Navy has conducted "freedom of navigation operations" to protest the actions taken by China and other claimants that undermine international law and freedom of navigation. The United States has also extended military support to the Philippines, a treaty ally, and in May 2016 ended a long-standing arms embargo on Vietnam.

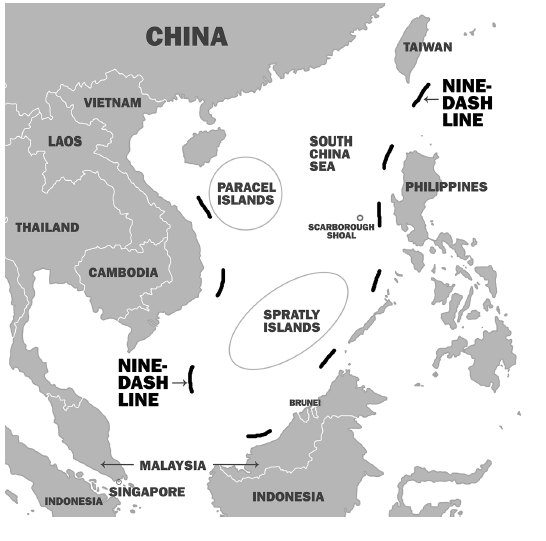

China has responded to these American moves with provocative policies that have only made the dispute worse and encouraged tougher American responses in turn. Examples of Chinese behavior include stationing anti-ship cruise missiles and fighter aircraft on Woody Island and using fishermen as "maritime militia" to harass other fishing boats. The most prominent attempt to peacefully resolve South China Sea issues was an arbitration case raised by the Philippines that challenged the legality of Chinese territorial claims. The case was heard by a tribunal at the international Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. On July 12, 2016, the court's ruling declared China's claims to sovereignty and historic rights within its infamous "nine-dash line" (see Figure 71.2) to be unlawful, clarified the legal status of many land features within the Spratlys, and admonished China for the ecological damage caused by island building.

The court's ruling represents an opportunity for the United States and China to move away from the dangerous and counterproductive escalation of tensions that has dominated the South China Sea in recent years. As of this writing, Chinese officials have released fiery statements about the illegitimacy of the ruling, but China has not demonstrated any serious escalatory behavior. Policymakers in Washington should support openings for negotiations among the South China Sea claimants, resource-sharing agreements, or other opportunities for peaceful management of disputes in the wake of the arbitration court ruling. Beijing will not give up its core policy positions any time soon; but if short-term de-escalation is possible, the United States would be foolish to continue with policies that increase escalation risks. Above all, Washington must be careful not to create the impression that it might back the claims of China's rivals militarily. That is especially pertinent regarding the Philippines, given the bilateral defense treaty with that country. This does not mean that shows of military force or support for allies should be completely halted, but rather used sparingly and as a component of a broader diplomatic strategy that emphasizes peaceful settlement of disputes.

Figure 71.2

China Territorial Claims in South China Sea

The long-standing dispute between Taiwan and mainland China, which views the island as a part of its territory occupied by a rebellious government, does not carry the same kind of risk as the South China Sea dispute. Conflict between China and Taiwan, which would probably draw in the United States, is not as likely in the near term. However, America's implicit security commitment to Taiwan under the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act is a ticking time bomb. Growing Chinese military power poses significant challenges to U.S. military forces that would rescue Taiwan, and domestic political issues in Taiwan make reunification with China less and less likely.

Cross-strait relations have deteriorated since the landslide victory of Taiwan's independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party in the January 2016 presidential and legislative elections. For example, in June 2016, Beijing announced that it had suspended a communication mechanism between the Taiwan Affairs Office and its Taiwanese counterpart, the Mainland Affairs Council, because of Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen's refusal to accept the idea of "one China." Most people in Taiwan, and especially younger generations, see themselves not as Chinese people living in Taiwan, but as Taiwanese people. Support for reunification with China is very low; a survey conducted in early 2016 by the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation found that 51.2 percent of respondents favored independence at some point in the future while only 14.9 percent preferred reunification with China.

U.S. policymakers should reconsider the wisdom of the implicit security commitment to Taiwan, and do so promptly. Impatience or miscalculation on the part of Beijing, rash action on the part of pro-independence Taiwanese, or a bad accident could trigger a crisis with devastating consequences for the United States. Although ideally it would be useful to keep Taiwan out of Beijing's clutches, the costs of maintaining the implicit security commitment now outweigh the benefits. Stepping down from the security commitment to Taiwan would not preclude Washington from selling weapons systems to Taiwan for defense against China and maintaining economic and political support for the island, and the United States should continue to do so.

China's struggle with Japan over control of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea is the final territorial dispute straining the U.S.China relationship. America's military alliance with Japan ought to be maintained, but Washington's insistence that the alliance covers the disputed islands in the East China Sea puts the United States in a risky position. Tensions between Beijing and Tokyo have been rising over the dispute for several years. In an armed conflict between China and Japan over the Senkakus/Diaoyus, the United States would be expected to risk war with China over a few uninhabited rocks. That is an unwise risk for the United States.

Cyber Espionage against U.S. Companies

Well-publicized intrusions into U.S. government and commercial networks have made cyber espionage, especially as it relates to the theft of American intellectual property, a source of friction in U.S.-China relations. China's use of cyberspace for intelligence collection targeting the U.S. government, military, and intelligence agencies is to be expected. But the United States government considers the theft of intellectual property by Chinese agents for commercial or strategic gains to be unacceptable.

During his September 2015 visit to Washington, president Xi Jinping of China reached a cyber agreement with the United States. One of the key provisions of the agreement was a pledge that neither country would "conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors."

Despite the agreement, skepticism persists regarding Beijing's intentions and willingness to rein in cyber espionage against U.S. companies. A June 2016 report by FireEye, a cyber security firm, suggests that while progress has been made in reducing Chinese cyber espionage, skepticism is still warranted. The report indicates that the number of Chinese cyber espionage activities against U.S. companies has decreased significantly, but the threat has become "more focused, calculated, and still successful in compromising corporate networks." Also, the September 2015 cyber agreement was just one of several factors, including U.S. government pressure and Xi's military reforms, that contributed to the shift to fewer but higher-quality cyber espionage operations.

Cyber espionage against U.S. companies will remain a sore spot in U.S.Chinese relations for the foreseeable future. Policymakers in Washington should continue applying diplomatic pressure on Beijing, but they must not overhype the threat posed by cyber espionage for commercial gain. Likewise, Chinese activities in cyberspace that target U.S. military and intelligence capabilities should be guarded against but not overblown. The task of successfully incorporating stolen information into the Chinese economy or military can be much more difficult than stealing the information. American policymakers should also eschew threats to respond to cyberattacks with kinetic force.

American Primacy

The United States has enjoyed an overwhelmingly dominant position in East Asia since the end of World War II, and U.S. officials seem determined to preserve that position of primacy. But enough changes have taken place since the end of the Cold War that such an approach is no longer the optimal strategy. Indeed, it soon may not even be a feasible strategy given the excessive costs and risks that it incurs. Public statements by American military and political leaders that U.S. actions are not intended to prevent China's rise have not allayed Beijing's fears of containment.

A different strategic approach — one that downplays the role of forward-deployed military forces and places more responsibility on U.S. allies and other significant regional actors for balancing against Chinese power — would reduce the risk of U.S.-China conflict. Instead of trying to preserve a fading primacy, policymakers in Washington should focus on sustaining a narrower list of crucial U.S. interests in East Asia. Preserving freedom of navigation should be a high priority, given America's naval and commercial interests. Promoting a regional balance of power that can serve as a check against Chinese aggression with minimal American input would preserve stability in East Asia while reducing the main sources of dangerous friction in U.S.-China relations.

Managing relations with a rising great power is never easy, and this is certainly true with China. History is replete with examples of incumbent hegemons and rising powers colliding militarily, and with tragic results. The rise of Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, culminating in the onset of World War I, is a sobering reminder of a worst-case outcome for U.S.-China relations. Policymakers in the next administration need to make some tough choices to protect America's interests while avoiding needless conflicts with China.

Suggested Readings

Bandow, Doug, and Eric Gomez. "Further Militarizing the South China Sea May Undermine Freedom of Navigation." The Diplomat, October 22, 2015.

Carpenter, Ted Galen. "How Beijing Is Countering U.S. Strategic Primacy." China-U.S. Focus, June 21, 2016.

---. "Persistent Suitor: Washington Wants India as an Ally to Contain China." China-U.S. Focus, April 29, 2016.

Goldstein, Lyle J. Meeting China Halfway. Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2015.

Lindsay, Jon R. "The Impact of China on Cybersecurity: Fiction and Friction." International Security 39, no. 3 (Winter 2014/15): 7-47.

Rosecrance, Richard N., and Steven E. Miller, eds. The Next Great War? The Roots of World War I and the Risk of U.S.-China Conflict. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2015.

Silove, Nina. "The Pivot before the Pivot: U.S. Strategy to Preserve the Power Balance in Asia." International Security 40, no. 4 (Spring 2016): 45-88.