I want to make five points.

First, it's important to understand that America's chief fiscal problem is an excessive burden of government spending. That's true today, and, as yesterday's long-run CBO fiscal outlook demonstrated, too much spending is our problem in the future.

Deficits and debt are undesirable, of course, but so are high taxes and printing money, which are the other two ways of financing government spending.

Simply stated, the true fiscal tax on our economy is how much government is spending. That's the problem. Deficits and debt, by contrast, are symptoms of that problem. Overall government spending is the measure of how much money is being diverted from the economy's productive sector. That's the primary problem. The various ways of financing that spending are secondary problems.

Second, the best way to gauge the success of fiscal policy is to see whether the burden of government spending is growing faster or slower than private economic output. If the private sector is growing faster than the government — which I consider to be the Golden Rule of Fiscal Policy — then lawmakers are doing a good job.

But if the converse is true and the burden of spending is rising faster than the private sector, then policy is heading in the wrong direction.

The data for any one year is important, but the real test is what happens over time. In other words, fiscal trendlines are critical.

If government spending grows slower than the productive sector of the economy for an extended period of time, this almost certainly means better economic performance because the relative burden of government is declining. And because the problem of spending is being properly addressed, this also means that the symptom of red ink almost certainly is falling as well.

But if the opposite occurs, and government grows faster than the private sector for an extended period, then it's just a matter of time before serious fiscal and economic problems occur. Nations such as Greece, for instance, got in trouble because the politicians did the opposite of the Golden Rule of Fiscal Policy.

Third, it's possible to make rapid progress with even a modest amount of spending restraint. Consider what's happened the past two years. For the first time in more than 50 years, we've enjoyed two consecutive years when overall government spending was lower than the previous year.

This has led to a big improvement in the key fiscal indicator, with the burden of federal government spending falling from 24.1 percent of GDP to 21.5 percent of economic output. And because there was progress on the real problem, the symptom of red ink got much better as well, with the deficit falling by more than 50 percent, from $1.3 trillion to $642 billion.

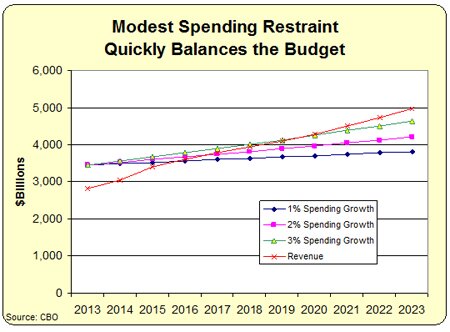

We don't even need that degree of fiscal discipline going forward. As illustrated by this chart, we can balance the budget in just 3 years if spending grows by an average of 1 percent annually. Red ink disappears in 4 years if spending grows by an average of 2 percent per year. And the deficit goes away in 7 years if spending grows by an average of 3 percent each year.

Indeed, it’s worth noting what Canada achieved in the 1990s. The burden of government spending had reached crisis levels by 1992, with government consuming more than 50 percent of economic output. But Canadian lawmakers — primarily during a time when the Liberal Party was in charge — put the brakes on spending.

For a period of five years, government outlays grew by an average of just 1 percent per year. That dramatically reduced the burden of government relative to the private sector. And by dealing with the underlying problem, Canada also went from having a large deficit of about 9 percent of GDP to a budget surplus.

Let’s now deal directly with the debt ceiling. My fourth point is that an increase in the debt ceiling is not needed to avert a default. Simply stated, the federal government is collecting far more in revenue than what’s needed to pay interest on that debt.

To put some numbers on the table, interest payments are about $230 billion per year while federal tax revenues are approaching $3 trillion per year. There’s no need to fret about a default.

But don’t believe me. Let’s look at the views of some folks that disagree with me on many fiscal issues, but nonetheless are not prone to false demagoguery.

Donald Marron, head of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and former Director of the Congressional Budget Office, explained what actually would happen in an article for CNN Money.