Thank you for inviting me to testify today. My name is Romina Boccia. I am the Director of Budget and Entitlement Policy at the Cato Institute. The views I express in this testimony are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of the Cato Institute.

I will make three main points:

First, higher spending, and particularly spending that’s growing faster than the economy, is driving the growth in the public debt.

Second, the growth in Medicare and Social Security spending is the primary driver of the growth in public debt.

Third, entitlement reform must be coupled with pro-growth policies to secure America’s fiscal future and economic prosperity.

Growing spending is at the root of the debt problem.

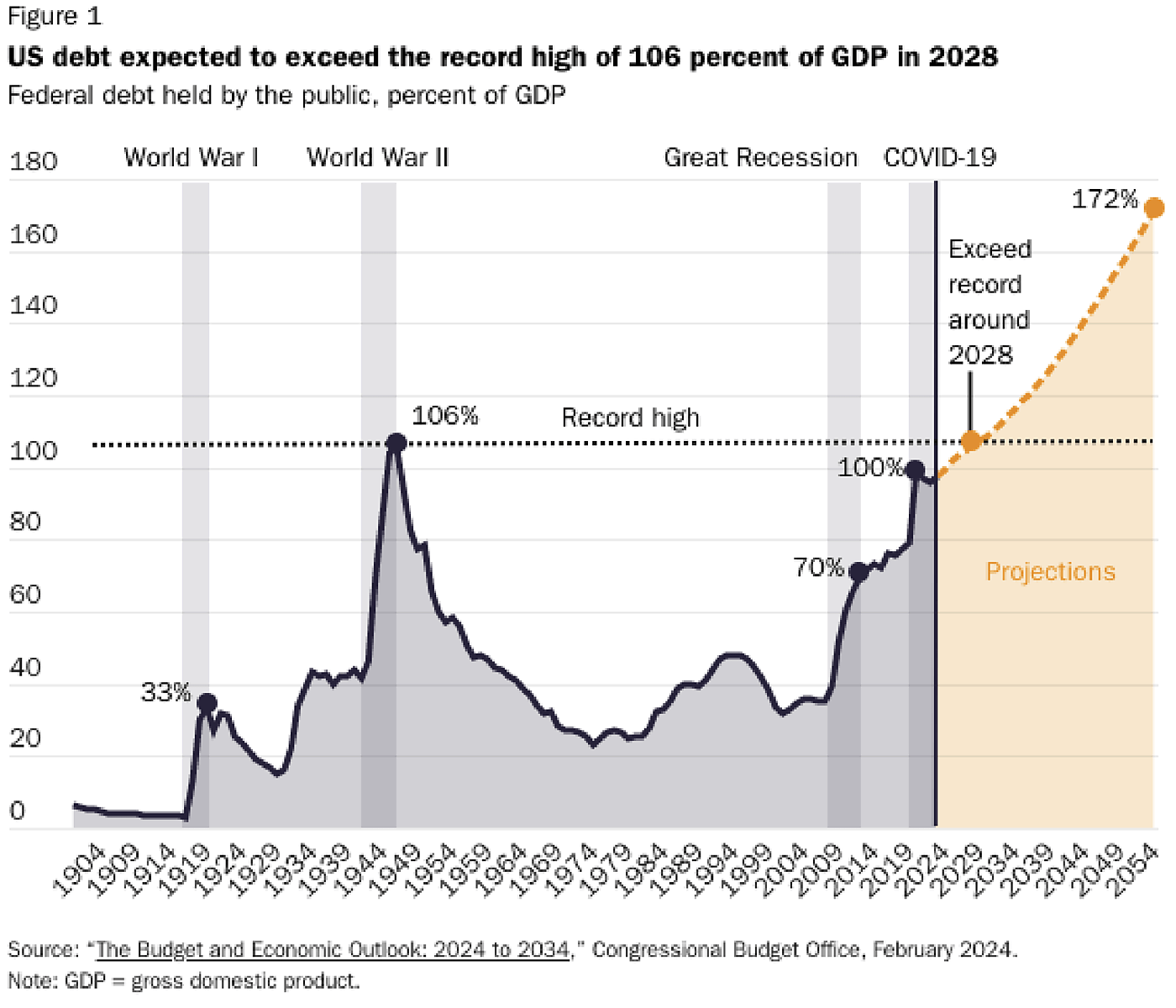

Our nation’s debt is growing at an alarming rate, and this growth is primarily driven by increased government spending. According to the February Congressional Budget Office (CBO) outlook, Social Security and federal health care programs are the largest programmatic causes of spending‐based deficit growth, with publicly held debt projected to reach an unprecedented 172 percent of GDP by 2054 (see figure 1 below).1

Between 2024 and 2034, Social Security spending will grow from $1.5 trillion to $2.5 trillion, annually. Over the same time frame, major health care programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, will grow from $1.6 trillion to $2.8 trillion, annually. Combined, Social Security and major federal health care programs represent 63 percent of spending growth over the next decade.

Interest costs are the other major driver of higher spending over the next decade. From 2024 to 2034, interest costs are projected to grow from $870 billion to $1.6 trillion, or by 87 percent.

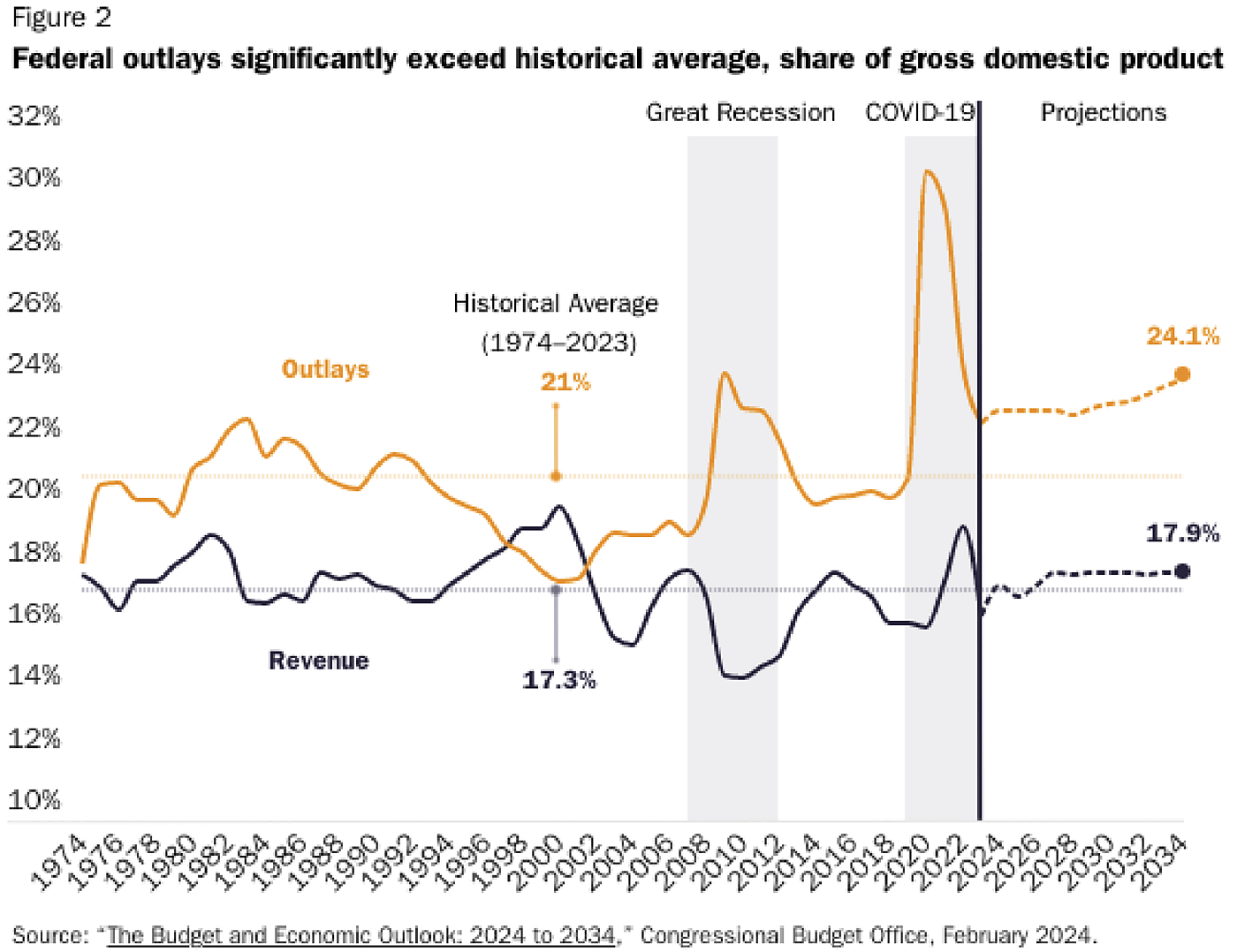

While CBO projects outlays growing from $6.5 trillion in 2024 to $10 trillion in 2034, a 54 percent increase, the nonpartisan agency projects tax revenues will also increase from $4.9 trillion in 2024 to $7.5 trillion in 2034, a 51 percent increase. This is a highly unrealistic projection given that neither political party has demonstrated an appetite for allowing the 2017 middle class tax cuts to expire, as scheduled under current law. As my Cato colleague, Dr. Adam Michel, has written: “There is broad bipartisan support to extend about three‐quarters of the tax cuts.”2

Instead, spending will continue to outpace revenue, as has been the case during most years in recent US fiscal history. The ongoing gap between spending and revenue becomes more apparent when comparing current CBO projections to historical averages (1974–2023). As shown in Figure 2, projected outlays are significantly higher than the 50-year historical average. Even assuming CBO’s revenue projections hold, a highly unlikely proposition, significantly higher taxes will not catch up with rapid spending growth.

If the federal government continues this unsustainable fiscal path, we risk burdening future generations with excessive debt, slower economic growth, higher interest rates, and reduced income levels. There’s also the increased risk of a severe US fiscal crisis if investors lose faith in the government’s willingness or ability to service its debt in full. There’s a limit to a country’s fiscal space, determined by the strength of its economy and the robustness of its institutions.

One category of spending that CBO cannot effectively predict is Congress’s propensity to temporarily and significantly increase spending to respond to crises. According to our research at the Cato Institute, Congress has designated $12 trillion in spending for emergencies over the past 30 years.3 That’s equivalent to 43 percent of the total publicly held debt. My co-author and I also identified that the portion of spending attributable to emergency responses makes up 12 percent of total budget authority over the past decade.

Major emergencies have a big impact on the budget. The two largest increases in federal debt over the last three decades were directly related to the extraordinary emergency fiscal responses to the Great Recession and COVID-19 pandemic. If history is destiny, the next major crisis and its fiscal response could significantly contribute to—and accelerate—America’s fiscal decline. Legislators should keep this in mind as they process the CBO’s latest outlook, prepare budgets, and consider new policy proposals. Our nation is on an unsustainable and highly risky fiscal path, before considering any unexpected emergencies that will likely trigger a major fiscal response.

Federal spending sprees in response to emergencies such as World War II, the Great Recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic were possible because bond markets were willing to take on greater federal debt. If bond markets were unwilling to finance future spending sprees, high debt could constrain the United States’ capacity to respond to future emergencies. Alternatively, bond market tightening in the face of an emergency could put the Federal Reserve under pressure to monetize US government spending, which could trigger disruptive inflation that would hurt vulnerable populations the most. We saw this play out following the pandemic, when inflation reached a 40-year high following the Federal Reserve’s creation of about $5 trillion in new money to support government spending. Legislators should seriously grapple with these inevitable tradeoffs and stabilize spending growth to stabilize the debt, while the economy is relatively strong, rather than waiting for a fiscal crisis or other emergency to force their hands.

The automatic growth of Medicare and Social Security spending is the biggest issue Congress must solve.

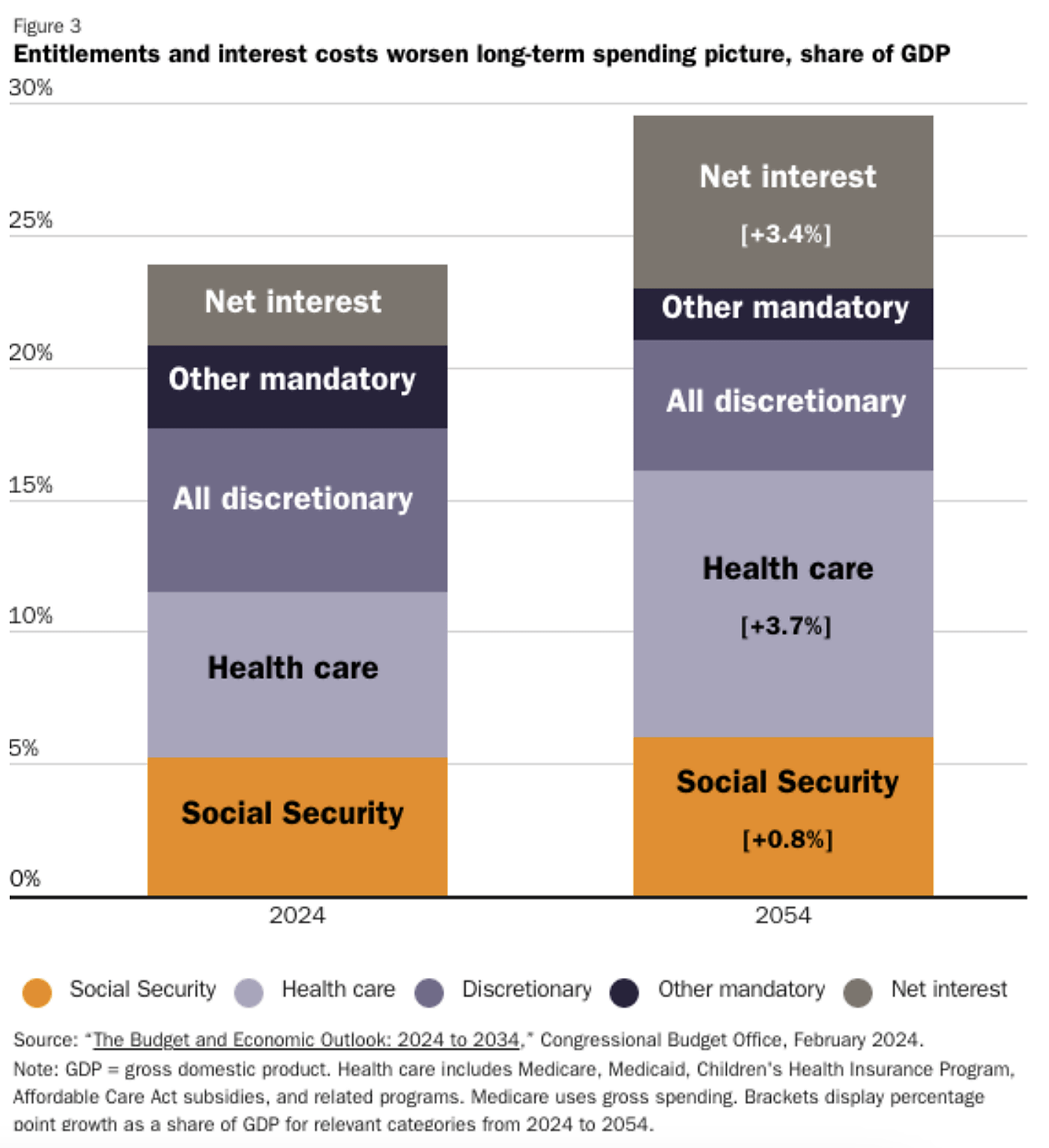

As I covered above, major health care programs and Social Security are the biggest spending growth drivers over the next decade, alongside increasing debt service costs. Over the longer‐term 30‐year spending window, Social Security, health care programs, and interest costs continue to be the biggest spending issues, threatening to drive federal spending to 30 percent of GDP.

These three budget categories, major health care programs, Social Security, and interest on the debt, will grow by 8 percentage points of GDP from 2024 to 2054. Every other major budget category declines or stabilizes as a percentage of the economy over the same period, according to current policy projections by CBO. Figure 3 displays major budget categories as a share of GDP.

They key drivers of rising US deficits and debt are apparent as Medicare, other health care programs, and Social Security expand as a percentage of GDP, alongside the rising cost of servicing the debt. Congress cannot effectively address the short-term nor long-term growth in the federal debt, without addressing old age benefit programs and the growth in health care spending. Meanwhile, the only effective way to address the cost of interest on the debt is to stabilize the debt and reduce annual deficits, which contribute to rising interest costs.

Old-age benefit programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, are on an unsustainable path due to demographic changes and rising healthcare costs. But most importantly, these programs are on an automatic growth trajectory due to past legislation that failed to curb their spending growth and neglected to bring these programs in line with economic growth and reasonable tax revenue projections.

Over the yet longer-term, the Financial Report of the United States Government (also known as the Financial Report) details how U.S. taxpayers face over $73 trillion in long‐term unfunded obligations over the next 75-years.4 What’s more, this unfunded obligation is entirely driven by only two federal government programs: Medicare and Social Security.

That’s correct. Over the next 75 years, Medicare and Social Security funding shortfalls comprise 100 percent of the total unfunded obligation. Medicare and Social Security’s funding shortfalls will amount to $78.3 trillion, which is $5.1 trillion more than the total unfunded obligation. This indicates a $5.1 trillion surplus in the non-entitlement parts of the budget, which offsets the total Medicare and Social Security unfunded obligation.

Without significant reforms, these old-age benefit programs will continue to drive US debt higher and could trigger a severe fiscal crisis within this generation’s lifetime. As the baby boomer generation continues to age, the number of beneficiaries drawing benefits from these programs will increase, further exacerbating the funding issue.

Congress should consider benefit reforms to reduce spending and secure the long-term solvency of these programs. Effective reforms include raising eligibility ages to reflect rising life expectancies, more progressive benefit targeting, and reducing benefit cost growth, through encouraging greater reliance on private savings and changing the initial Social Security benefit formula to index earnings to changes in the cost of living rather than wages,5 and by leveraging market forces in healthcare to reduce prices while preserving access to quality care.6

Entitlement reform must be coupled with pro-growth policies to secure America’s fiscal future and economic prosperity.

While it is crucial to get our fiscal house in order, we must also focus on policies that promote economic growth. A strong, growing economy can generate the revenues needed to help reduce the debt. But not all deficit reduction is the same. Short-sighted policies that raise taxes on investment and work can have the opposite effect as intended. As my Cato colleague, Dr. Adam Michel, has written: “[S]tudies consistently show a positive effect of tax cuts on investment and economic growth. When you lower effective tax rates on work and investment, you should expect to get more of each.”7 The flipside also holds. When you raise taxes on work and investment, you should expect less of each. If legislators opt for policies to raise revenues which undermine economic growth, legislators will likely fall short of their goal of stabilizing the debt.

A Heritage Foundation report distilling lessons from European austerity measures, of which I am a co-author, details why increasing taxes is less effective in reducing deficits than spending cuts. Furthermore, a tax-first approach can damage the economy. The most successful fiscal adjustments, judged by their impact on deficits and the economy, reformed social programs and reduced the size and compensation of the government workforce.8

Andrew Biggs, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI); Kevin Hassett, formerly a scholar at AEI; and Matthew Jensen, then the founding director of the Open Source Policy Center, drew similar conclusions, writing that:

Spending‐based fiscal adjustment accompanied by supply‐side reforms‐such as liberalization of the markets for labor, goods, and services; readjustments of public‐sector size and pay; public pension reform; and other structural changes‐tend to be less recessionary or even lead to positive economic growth.9

Congress should commit to a credible fiscal stabilization path that controls the growth in the debt as a percentage of GDP. To succeed, Congress should focus on curbing the growth in old-age benefit programs and limiting spending across the federal budget, from discretionary to other mandatory, and by adopting effective limits and offsets for emergency-designations and similar cap-exempt spending. Following excessive spending during the COVID-19 pandemic that contributed to inflation reaching a 40‐year high, Congress should shift gears by pursuing deficit reduction that enables economic growth.

Spending‐based deficit reduction, especially targeted at social and entitlement programs, is most effective at sustainably reducing deficits and the growth in the debt as a percentage of GDP. While revenues are likely to be part of any politically realistic deficit reduction proposal, legislators should focus on closing special interest loopholes that distort markets by subsidizing certain spending and investments for political preference reasons. Such spending through the tax code undermines broad-based growth and fairness, by creating political winners and losers. Congress should also avoid short-sighted revenue policies that would undermine work and investment. While economic growth won’t get us out of the spending-driven debt crisis, an expanding economy will certainly help ease the transition.

There’s light at the end of the tunnel.

As bleak as the US fiscal outlook is, there is light at the end of the tunnel. The House Budget Committee recently passed the Fiscal Commission Act, which seeks to stabilize the debt over 15 years, educate the public on the nation’s deteriorating fiscal state, and improve the Medicare and Social Security’s trust funds’ solvency over a 75‐year window.10 This is a positive step toward bringing more attention to the nation’s rapidly deteriorating fiscal state and advancing proposals to address it. Still, the current approach has certain shortcomings, such as including only elected officials as voting members on the commission and requiring an affirmative vote before proposals can go into effect.

The most promising approach would be modeled after the successful Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process. A BRAC‐like fiscal commission would be independent, involve the president, and its recommendations would be expedited in Congress through silent approval. A well‐designed fiscal commission, alongside other budget reforms that limit spending and the growth in the debt, could put the United States on a better path that enables this and the next generation to enjoy a freer, more vibrant, and stronger America.

I look forward to answering your questions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.