One of Dodd-Frank’s most contentious provisions is Section 922, which directs the Securities and Exchange Commission to implement a “whistleblower” program by which individuals may report suspected securities violations to the agency. Previously, SOX’s Section 301 had required firms’ audit committees to establish and monitor whistleblower programs by which suspected violations could be reported internally, but Dodd-Frank elevates whistleblowing by enabling employees, vendors, and customers, among others, to bypass companies’ internal control systems and report accusations directly to the U.S. Government. Dodd-Frank further stipulates that whistleblowers could receive as much as 30 percent of any fines, penalties, or the repayment of losses resulting from their reports.

Firms, attorneys, and others have been vocal about the potential for harm associated with the Dodd-Frank whistleblowing mechanisms. The SEC received over 950 comment letters following its publication of proposed rules for implementing Section 922. In particular, concerns have been expressed about the potential for disgruntled individuals to make unsubstantiated accusations in an effort to gain financial rewards, and the potential adverse impact of false claims on stock prices and customer and vendor relationships.

In this article, we attempt to determine how heavily the Dodd-Frank whistleblower bounty program might be utilized and the likelihood that it would be successful in its mission to “encourage people to report securities violations.” We do this by examining two analogous federal bounty programs, the Federal False Claims Act of 1863, as amended in 1986 and 2008, and the Internal Revenue Service’s Informant Claims Program. Our results suggest that, although rewards under these programs may be substantial, general use of the programs is not high. In light of Dodd-Frank’s similarities to these programs, and an expected lack of adequate federal funding to pursue reported claims, it is likely Section 922 will have similar results.

Comparing Whistleblower Programs

The United States has used whistleblower programs for almost 150 years. Below is a brief description of three of these programs, along with the Section 922 program.

The FFCA | The Federal False Claims Act (FFCA) offers incentives to individuals who report companies or individuals defrauding the government. It was implemented by President Lincoln in 1863 to protect the United States from purchases of fake gunpowder during the Civil War. Claims under the FFCA are typically related to health care or the military, and often report over-billing or billing for fraudulent services. Reporting of suspected tax fraud is excluded under the FFCA and instead is covered by the IRS’s whistleblower program described below.

As amended in 1986 and 2009, the FFCA offers financial incentives to whistleblowers of up to 30 percent of any recovery. It also includes anti-retaliation provisions including reinstatement, damages, and double back pay for workers who report their employers. Claims under the FFCA are filed with the Department of Justice under seal, meaning they will not be made public until the government decides to intervene. Claims cannot be brought against members of the armed forces, the judiciary, Congress, or senior executive branch officials.

To reduce the likelihood of false accusations, the FFCA imposes monetary penalties on individuals reporting false claims. Some states have enacted laws similar to the FFCA.

ICP | The Informant Claims Program (ICP), implemented under Section 7623 of the Internal Revenue Code, has been in effect since 1867. Under the ICP, an individual may report a taxpayer who underreports his tax liabilities, and the whistleblower could receive a bounty in return for the report.

The ICP’s only substantial modification came in 2006 when discretion of the amount of bounty paid to whistleblowers was removed, eligibility thresholds were enacted, and whistleblower appeals were provided. Under the program’s current form, if the IRS successfully uses the whistleblower’s information against an individual with adjusted gross income of at least $200,000 or an entity with underpayments of at least $2 million, the whistleblower is entitled to a bounty of up to 30 percent of funds collected, including taxes, penalties, and interest. Whistleblower bounties of up to 15 percent of recovered amounts are also available for smaller disputes. The IRS reserves the right to refuse payment of a bounty if the whistleblower is convicted of criminal conduct associated with the reported tax evasion.

SOX | The Sarbanes-Oxley Act’s Section 301 requires issuers’ audit committees to implement mechanisms for recording, tracking, and acting on information about potential securities violations provided by employees anonymously and confidentially. SOX Section 806 also broadened previous whistleblower protections to cover employees who report fraud to any federal regulatory or law enforcement agency, any member or committee of Congress, or any person with supervisory authority over the employee. Potential securities violations reported to a federal agency or an internal corporate compliance office under SOX carry no opportunity for financial bounty.

Dodd-Frank | To be eligible for a bounty under the Dodd-Frank Act’s Section 922, individuals — not organizations — must submit original information derived from the whistleblower’s independent knowledge pertaining to a corporation’s violation of securities laws. If the information results in a recovery, including fines and penalties, of at least $1 million from the accused corporation, the whistleblower may earn a bounty of 10–30 percent of the recovery. For example, if an employee supplies the SEC with a duplicate set of financial records that suggests his or her employer has reported falsified financial information and, as a result of the SEC’s investigation, the corporation is required to pay a $1 million fine, the whistleblower is eligible for a bounty of up to $300,000.

Individuals who are convicted of a crime related to the reported misconduct or who participate in reported violations are not eligible for the bounty. For example, if an employee of a foreign, government-controlled entity reports evidence of receiving a $10,000 bribe from a U.S. corporation to secure a $5 million contract and, as a result of the SEC’s investigation, the corporation must pay a $10 million fine under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the reporting individual would not be eligible for a bounty. Issuers’ internal compliance personnel, attorneys, auditors, and other recipients of privileged communications are also ineligible to receive bounties for claims related to their clients’ securities violations. Uncertainty as to how the SEC would treat a whistleblower under these proposed disqualification rules may discourage whistleblowers from filing claims.

Dodd-Frank also includes protections for the whistleblower against employer retaliation. In the event of successful claims, protections include the possibility of reinstatement, double back pay with interest, expert witness fees, and attorney fees.

Claims and Bounties Under Existing Whistleblower Programs

The frequently offered concern about the Dodd-Frank whistleblower provision is that it will prompt many baseless reports that will be costly to accused firms. However, the relatively few instances in which would-be whistleblowers — legitimately or not — have made use of the FFCA and ICP suggest that this concern may be overstated.

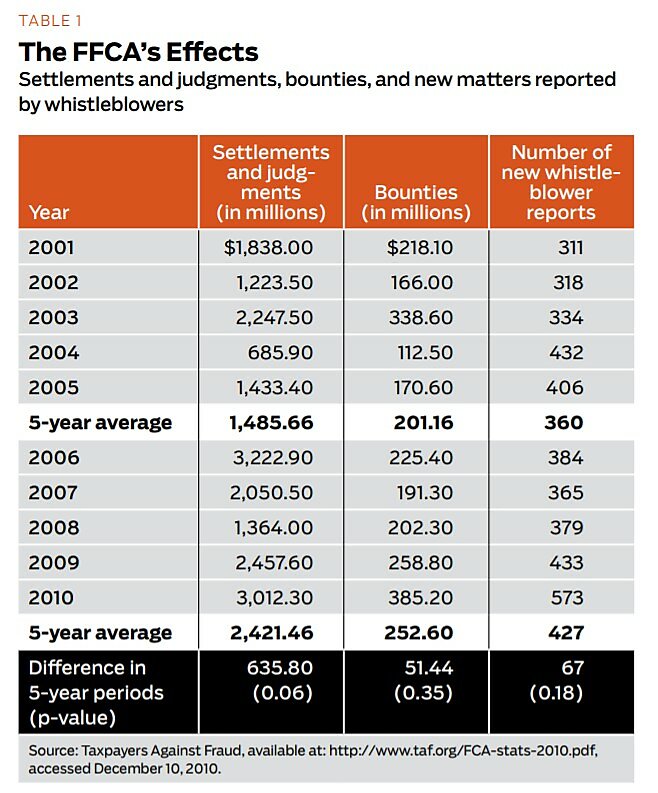

The Department of Justice recently reported that, for the fiscal year ended September 30, 2010, recoveries under the FFCA totaled roughly $3.0 billion, of which $2.5 billion related to health care fraud recoveries (exclusive of criminal penalties and recoveries passed along to states). Some $2.3 billion of those recoveries were the result of information reported by whistleblowers, who received approximately $385 million in bounties. Since 1986, bounties paid to whistleblowers have totaled a little over $2.8 billion.

Table 1 presents data made available by Taxpayers Against Fraud, an organization that actively encourages individuals to report fraud under the FFCA. The table summarizes FFCA settlements and judgments, bounty payments, and number of new matters reported by whistleblowers (i.e., qui tam matters) during the period from fiscal year 2001 to 2010.