Let me first commend the Chairman, along with Subcommittee Chair Campbell, on the establishment of the Federal Reserve Centennial Oversight Project. Every government program should be reviewed regularly and subjected to vigorous oversight. The American people deserve nothing less. I can think of no part of the federal government more in need of review than the Federal Reserve. Had vigorous oversight of the Federal Reserve been conducted in the past, we might have been able to avoid the creation of a massive housing bubble.

Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy

The release last week of January’s establishment (employer) survey of employment revealed continued weakness in the U.S. labor market. The 113,000 new jobs estimate was considerably below expectations; for instance the Dow Jones Consensus forecast was 189,000. It was also considerably below the monthly average for 2013 of 194,000. The unemployment rate dipped slightly to 6.6 percent, representing 10.2 million persons unemployed.1

There were a few minor bright spots in January’s labor market. The labor force participation rate rose slightly to 63%, with a 499,000 increase in the civilian labor force. The employment-population ratio slightly increased to 58.8 percent. And total employment, measured by the household survey, increased 616,000. We also witnessed a decline in the number of long-term unemployed by 232,000. Those marginally attached to the labor force, including discouraged workers, remained essentially flat. So while the improvement in the labor market was modest, it was real. Declines in unemployment were not driven, as in previous months, by workers leaving the labor force. That said, our labor market remains weak. Let me say unequivocally, the primary area of weakness in our economy is the labor market.

Over 40 percent of the job growth in January came from the Construction sector, a welcome and somewhat surprisingly increase. Until recently low mortgage rates have largely generated re-financing fees for banks and lower monthly payments for prime credit borrowers, along with higher home prices. The impact on construction and construction employment has been, up until January, quite modest.

There were a few minor bright spots in January’s labor market. The labor force participation rate rose slightly to 63%, with a 499,000 increase in the civilian labor force. The employment-population ratio slightly increased to 58.8 percent. And total employment, measured by the household survey, increased 616,000. We also witnessed a decline in the number of long-term unemployed by 232,000. Those marginally attached to the labor force, including discouraged workers, remained essentially flat. So while the improvement in the labor market was modest, it was real. Declines in unemployment were not driven, as in previous months, by workers leaving the labor force. That said, our labor market remains weak. Let me say unequivocally, the primary area of weakness in our economy is the labor market.

Over 40 percent of the job growth in January came from the Construction sector, a welcome and somewhat surprisingly increase. Until recently low mortgage rates have largely generated re-financing fees for banks and lower monthly payments for prime credit borrowers, along with higher home prices. The impact on construction and construction employment has been, up until January, quite modest.

Outside construction the remainder of job gains were concentrated in professional/business services (+36,000), leisure and hospitality (+24,000) and manufacturing (+21,000). Most of the decline in government jobs was the result of downsizing by the Postal Service. Despite the increase in manufacturing jobs, the average workweek (in hours) and overtime hours declined slightly.

In general the decline in unemployment was shared by most demographic groups, with some exceptions. Teenagers witnessed a slight up-tick in unemployment, as did African-American, Asian and Hispanic workers. December to January witnessed a significant jump in unemployment among African-American teenagers (32% to 39%). This increase is actually understated as the labor participation rate decline substantially for African-American teenagers; had it remained constant the increase in unemployment would have been higher. On an unadjusted (for seasons) basis, the number of employed African-American teenagers fell almost 15 percent from December to January. Seasonal adjustment reduces part of this decline, but not all. It is too early to tell whether this slight increase from December to January was related to a small number of states increasing their minimum wage on January 1st, which generally has a greater impact on the unemployment rate of teenagers. Certainly some of this decline is a result of the end of the holiday temporary hiring, but by no means all. The trend in employment among teenagers merits continued scrutiny as this may offer some indication as the availability of entry-level employment.

While we must address our long term fiscal imbalances, particularly Medicare, immediate policy discussions should begin and end with the labor market. While I am in broad agreement with emphasis placed on jobs, I do not believe our current fiscal, regulatory and monetary policies have been conducive to job creation. In fact I believe all of the above have worked against job creation. We all are aware of the Albert Einstein definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Our economic policies must radically change direction if we are to expect significant improvement in our economy.

The mantra of the Federal Reserve, as well as those who argue for Keynesian fiscal stimulus, is that all of our macroeconomic problems can be fixed if we simply increased aggregate demand. Of course increases in demand can result in increases in employment, holding all else equal. What has made me skeptical of “demand hole” theories of our current macroeconomic environment is that demand, as measured by consumer spending or GDP, has steadily increased since Summer 2009. However employment did not keep pace with that increase, showing a breakdown in what economists call Okun’s Law. One might attribute this breakdown to increased productivity, but that only answers one question with another. Changes in productivity are endogenous to our economy. If the cost of labor increases relative to capital, employers will substitute capital for labor. Of course capital and labor are both substitutes and compliments; whichever effect will dominate at any one time is a matter of a many forces.

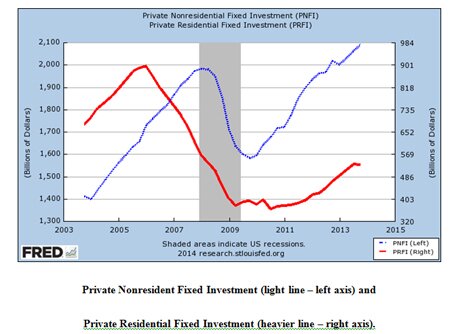

One of the inputs to the relative cost of labor versus capital is the interest rate. Lower interest rates generally lower the cost of capital. One hope with traditional monetary policy is that a lower interest rate will spur investment that is complimentary to labor, thereby increasing employment. It is possible as well that declines in the interest rate spur the substitution of capital for labor. Given the recovery in private nonresidential fixed investment, which did follow a “V” shape pattern, and the trend in productivity (real output per hour has increased over 10 percent since 2009), there is some reason to suspect that monetary policy has, in the short run, led to the substitution of capital for labor, perversely increasing unemployment.

Another hope of monetary policy is that reductions in interest rates will increase asset prices by reducing the discount rate at which future cash flows are discounted, in addition to nudging liquidity into particular asset markets. The objective is not to increase asset prices for their own sake, but to create a “wealth effect” whereby households feel richer due to higher asset prices and then increase consumption, increasing aggregate demand and thereby increasing employment. While I believe it is undeniable that Federal Reserve policy has increased the value of a variety of assets, such as homes and equities, and that these policies have exasperated inequalities in wealth (by benefiting current asset owners), I also believe those consequences are not the primary objective of the Federal Reserve. However as Milton Friedman reminded us, we should not judge government policies by their intents but by their results. The result of current Federal Reserve policy has been to inflate asset prices, increase economic inequality with little positive impact on the labor market.

Although current monetary policy has been quite beneficial to the holders of assets, it has not necessarily helped savers. One of the claimed benefits of low rates is that they reduce interest payments by households with debt, and that such reduced payments increases disposable income, which should increase consumption and eventually employment. Indeed mortgage interest payments have fallen on an annual basis almost $200 billion since 20082 . While a significant percentage of that is due to a reduction in overall mortgage debt, which has declined by just over $1 trillion since 2008,3 my estimate is that about $130 billion of that decline is the result of lower rates. But such only tells us half the story. During this same time the interest income paid to households, as savers, has decline by $134 billion.3 The point is that declines in household interest expenses have been off-set by declines in household interest incomes.

One might argue that borrowers have a larger propensity to consumer than savers, which is something we do not know, but even if that were the case, then any increase in spending would be the net of increases by borrowers and declines by savers. In all likelihood this impact would be quite small, a few billions a year at best. There is also some reason to believe the impact is negative as it relates to net aggregate demand. Most of those who re-financed are good credits that did not need a lower monthly payment, while many savers are retired and struggling to get by on fixed incomes. I myself have re-financed my mortgage. And while I am happy to have had my monthly payment reduced, it has made almost no difference on my spending patterns. The point to remember is that a considerable degree of the impact of monetary policy is purely redistributive, rather than wealth increasing. There is some evidence to also suggest that this redistributive is also regressive. In general I do not believe the role of monetary policy should be to take from one group of citizens and give to another.

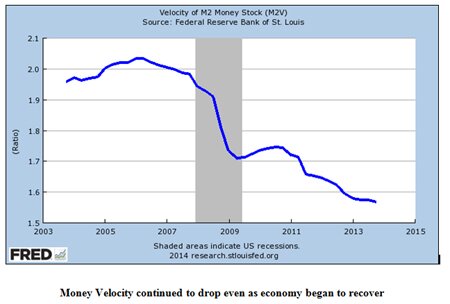

In general an objective of monetary policy is to stimulate borrowing from the banking system via open market operations. The hope is that expansions in the monetary base will ultimately lead to improvements in the real economy. Since late 2008 the Federal Reserve has engineered a massive increase in the monetary base. This increase led many, including myself, to be concerned about increases in inflation that could result from such an expansion in the monetary base. What some of us failed to appreciate was the extent to which the “plumbing” in our monetary system was broken. For the most part the increase in the monetary base remained in excess reserves held by commercial banks. Cash assets held by commercial banks have increased from under $400 billion in mid-2008 to almost $2.7 trillion. Plenty of liquidity has made its way into the banking system. Unfortunately it has gotten stuck there.

One reason for backed-up plumbing in our monetary system is the Federal Reserve reliance on a small number of institutional counterparties. There are currently only 21 “primary dealers” with which the Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy.5 These are supposed to be the safest of financial institutions, yet previously the set of primary dealers included such entities as Continental Illinois, Countrywide, Merrill Lynch, MF Global, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. The downside of this heavy reliance on so few institutions is that when these entities are themselves suffering liquidity problems, their effectiveness as conduits for monetary policy is reduced. They may end up, as Professor George Selgin has labeled them, “liquidity sinks”.6 My fellow panelist former Federal Reserve Vice Chair Donald Kohn has noted: