Concern about the impact of the trade deficit on growth is rooted in the assumption that rising imports displace domestic production in the U.S. economy, acting as a drag on the growth of real gross domestic product. As one wire service reported after the recent release of October’s record trade deficit number, “such a large trade deficit also threatened to be more of a drag on the domestic economy than first thought and could see analysts trim back expectations for GDP growth this quarter.”[4]

How valid is the widespread assumption that a growing trade deficit means slower economic growth? Hard evidence of such a connection appears to be lacking. In fact, an analysis of economic data from the last quarter century shows that a growing current account deficit (as a percent of GDP) is actually associated with faster, not slower, economic growth, as well as rising manufacturing output and falling unemployment.

Testing the Conventional Wisdom

Testing the Conventional Wisdom

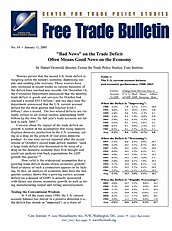

In 8 of the years since 1980, the U.S. current account balance has moved in a positive direction (i.e., the deficit has shrunk or “improved”) as a share of GDP from the previous year. In 16 of those years, it has moved in a negative direction (i.e., the deficit has grown or “worsened”). Of those years in which the balance moved in a negative direction, 10 have seen a moderate movement of between 0.0 and 0.5 percentage points, and 6 have seen a more rapid movement of 0.7 to 1.3 percentage points.[5]

How has the U.S. economy fared under each of those three current account scenarios? To address that question, Table 1 lists the size of the current account as a share of GDP for each year since 1980, along with the change in the current account percentage, real GDP,[6] manufacturing output,[7] and the unemployment rate[8] from the previous year. (Changes in manufacturing output and the unemployment rate are measured from December to December to more fully capture the trend of that year.) The years are grouped in three categories, according to the magnitude of change in the current account balance as a share of GDP.

As the table illustrates, by all three measures of economic performance‐GDP, manufacturing output, and the unemployment rate‐the U.S. economy performs better in years when the current account deficit is rising as a share of GDP than in years when it is shrinking. And it performs especially well in years when the current account deficit is rising most rapidly.

Trade Deficits, GDP, Manufacturing, and Unemployment

By the most basic measure of economic performance, the change in real GDP, evidence points to a stronger economy in years in which the current account deficit is rising. In those years since 1980 when the current account deficit declined as a share of GDP, the economy grew each year by an average of 1.9 percent. In those in which the current account deficit grew moderately, real GDP grew at an annual average of 3.0 percent. In those years in which the deficit most rapidly “deteriorated,” to borrow another popular characterization, real GDP grew by a robust annual average of 4.4 percent‑a rate more than double the growth in years when the deficit was “improving.” Four of the five best years for GDP growth since 1980 have occurred in the same years when the current account deficit was growing most rapidly.

The same pattern emerges in the manufacturing sector. It has become the conventional wisdom that a trade deficit hurts manufacturing because imports presumably displace domestic production, but the plain evidence of the past quarter century contradicts that presumption. Manufacturing output actually declined slightly on average in those years in which the current account deficit shrank. In contrast, it grew by 4.1 percent in years when the current account deficit grew moderately and by a brisk 5.3 percent when the deficit grew rapidly. In fact, five of the six years that saw a decline in manufacturing output occurred in years in which the current account deficit was declining.

The pattern also applies in the politically sensitive area of employment. Again, the conventional wisdom holds that a trade deficit destroys jobs by supposedly shipping them overseas. But again the evidence suggests something quite different. In those years of an “improving” current account deficit, the unemployment rate on average jumped by 0.8 percentage points. In years when the deficit moderately “worsened,” the unemployment rate fell by an average of 0.2 points, and in years when the deficit grew the most rapidly, the unemployment rate fell by an even larger average of 0.7 points. Indeed, in 7 of the 8 years in which the current account deficit “improved,” the unemployment rate went up; in 13 of the 16 years in which the current account deficit “worsened,” the unemployment rate went down.

The year 2004 appears to fit the pattern comfortably. Through the first three quarters of the year, January through September, the current account deficit averaged 5.5 percent of GDP, a 0.6 percentage point shift in the negative direction from 2003.[9] That would place 2004 somewhere between a moderate and rapid growth of the current account deficit. Befitting the pattern, economic performance through the first three quarters of the year was also moderate to robust. Real GDP grew an average annual rate of 3.9 percent during the first three quarters.[10] Manufacturing output grew during those same three quarters at an annual rate of 5.4 percent from the previous year,[11] while the unemployment rate was on a pace to drop by 0.4 percentage points during the full year.[12]

In 2004, as in previous years, a rising current account deficit may have been bad news to headline writers, but it appears to have accompanied good news for the U.S. economy, its factories, and its workers.

A Growing Economy, a Growing Trade Deficit

Evidence from the past 25 years directly contradicts the assumption that trade deficits impose a drag on the U.S. economy. Contrary to prevailing assumptions, “worsening” trade deficits are associated with faster GDP and manufacturing growth and more rapidly declining unemployment, while “improving” trade deficits are associated with slower GDP and manufacturing growth and rising unemployment.

The evidence does not suggest that expanding trade deficits cause the superior economic performance. More plausibly, causation runs the other direction. An expanding economy fuels demand by American consumers and producers to buy more imports as well as domestically produced goods and services while rising domestic output attracts the foreign investment that finances an expanding current account deficit. In contrast, slowing domestic demand not only depresses output and employment growth but also demand for imports and the inflow of foreign investment.

Nor does the evidence address the question of how persistent and rising current account deficits may affect the U.S. economy in the long run. The “sustainability” of the U.S. current account deficit has been addressed elsewhere in Cato studies.[13] But whatever negative impact the deficit may have in the long run, there is no evidence that it poses a drag on the economy in the short run.

Misperceptions about the trade deficit and the economy can tempt policymakers to “do something” about the deficit that would only hurt economic growth. The most obvious example would be raising barriers to imports in the mistaken belief that protectionism would cut the trade deficit and spur the economy. Even if higher trade barriers could somehow trim the trade deficit, there is simply no evidence that such a policy goal would deliver faster growth in GDP, manufacturing, and employment.

[1] U.S. Commerce Department, “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services Highlights,” news release, December 14, 2004, www.census.gov/indicator/www/ustrade.html.

[2] U.S. Commerce Department, “U.S. International Transactions: Third Quarter 2004,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, news release, December 16, 2004, www.bea.doc.gov/bea/di/home/bop.htm.

[3] The trade deficit is a subset of the current account deficit. It includes imports and exports of goods and services. The current account is the broadest measure of U.S. international transac‐tions, including goods, services, income on foreign investment, and unilateral transfers such as foreign aid. The two measures are closely related and can be used interchangeably for the pur‐pose of this analysis.

[4] Reuters, “Trade Gap Widens, Industrial Output Up,” December 14, 2004.

[5] For the current account balance and nominal GDP for the years 1980 through 2002, see Council of Economic Advisers, The Economic Report of the President 2004 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, February 2004), Tables B‑1 and B- 103. For 2003, see Joint Economic Committee of Congress, Economic Indicators, pp. 1 and 36, www.gpoaccess.gov/indica-tors/ 04novbro.html. The current account balance for 1991 was adjusted by — $41 billion to remove the one‐time payments to the U.S. government that year by Gulf War allies.

[6] For changes in real GDP through 2002, see Council of Economic Advisers, Table B4, p. 289. For changes in 2003 and the first three quarters of 2004, see U.S. Commerce Department, Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Economic Accounts: Gross Domestic Product,” Table 1, www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/home/gdp.htm.

[7] For the index of manufacturing output (seasonally adjusted) in December of each year, see U.S. Federal Reserve Board, “Statistics: Releases and Historical Data,” G.17 Supplement, Table B00004, www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/ipdisk/ip.sa.

[8] For the unemployment rate in December of each year, see U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from Current Population Survey,” Unemployment Rate: Civilian Labor Force, Table LNS14000000, data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?ln.

[9] For nominal GDP through the first three quarters of 2004, see U.S. Commerce Department, Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Economic Accounts: Gross Domestic Product,” December 22, 2004, Table 3, www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/home/gdp.htm. For the current account balance through the first three quarters of 2004, see U.S. Commerce Department, “U.S. International Transactions: Third Quarter 2004.”

[10] See U.S. Commerce Department, Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Economic Accounts: Gross Domestic Product,” December 22, 2004, Table 1. According to the BEA, real GDP grew 4.5 percent in the first quarter of 2004, 3.3 per‐cent in the second, and 4.0 in the third, for an average growth of 3.9 percent.

[11] See U.S. Federal Reserve Board.

[12] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[13] Daniel T. Griswold, “America’s Record Trade Deficit: A Symbol of Economic Strength,” Cato Trade Policy Analysis no. 12, February 9, 2001, pp. 10–14.