On September 17th, Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D‑NY) and Bernie Sanders (D‑VT) went on Facebook Live to announce their introduction of the Postal Banking Act, a bill that would have the US Postal Service provide a “public option” in some retail banking services. Postal banking has been proposed many times in recent years as a progressive reform. The Joe Biden–Bernie Sanders “Unity Task Force Recommendations” document (p. 74) endorsed the idea in August as a way of “ensuring equitable access to banking and financial services.” Senator Gillibrand introduced a similar bill two years ago, and an organization called The Campaign for Postal Banking has been promoting the idea since 2014.

An important impetus for the recent interest was a 2014 white paper by the Inspector General of the USPS entitled “Providing Non-Bank Financial Services for the Underserved.” The Executive Summary of the white paper (p. i) argued that “The Postal Service is well positioned to provide non-bank financial services to those whose needs are not being met by the traditional financial sector.” The USPS report in turn drew on a 2012–13 series of reports and reform proposals regarding payday lending by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Postal banking has been tried before in the US, as Diego Zuluaga has recently reminded us. Congress enacted a Postal Savings system in 1910, — following the Panic of 1907 — mainly as a means for the public to hold deposits guaranteed by the federal government. Postal Savings account balances peaked in 1947 at $3.4 billion, about 2.8 percent of the volume of total commercial bank deposits ($119.42. billion). By 1964 postal balances had shrunk to only $416 million, around 0.1 percent of bank deposits ($371.7 billion).[1] Congress ended the system in 1966, thirty-some years after federal deposit insurance had made it obsolete for guarantee purposes.

The text of the Gillibrand-Sanders bill authorizes the US Postal Service to provide:

- ”(A) low-cost, small-dollar loans, not to exceed $500 at a time,” or $1,000 in total loans over the course of a year (these loan amounts indexed to the CPI‑U), at total annual percentage rates, inclusive of fees, that “do not exceed 101 percent of the Treasury 1 month constant maturity rate,” a rate that currently stands at 0.08%;

- “(B) small dollar lending servicing”;

- “(C) small checking accounts and interest bearing savings accounts” up to $20,000 per account, with the savings accounts paying interest rates at or above the FDIC’s “weekly national rate on nonjumbo savings accounts,” an average of rates paid by commercial banks that currently stands at 0.05%;

- “(D) transactional services, including debit cards, automated teller machines, online checking accounts, check-cashing services, automatic bill-pay, mobile banking, or other products”;

- “(E) remittance services” for sending funds to domestic or foreign recipients; and

- “(F) such other basic financial services as the Postal Service determines appropriate.”

The bill and other recent proposals for postal banking seek to provide a consumer-friendly alternative to the (state-regulated) payday lending and check-cashing services presently used by the unbanked. A secondary objective is to turn a profit for the deficit-laden USPS. An economist’s first question of any proposal for a government-sponsored enterprise is naturally: What’s the evidence that the existing market is inefficient? Undeniably, interest rates on payday loans are high relative to interest rates on other loans, but is there reason to think that the higher interest rates aren’t necessary to cover higher loan default rates, leaving payday lenders a normal rate of return?

The Gillibrand-Sanders bill seems to neglect loan default risk entirely. The maximum loan interest rate that it allows the Postal Bank to charge is virtually equal (101 percent of 0.08 is 0.0808) to the default-risk-free rate at which the US Treasury borrows money. It is well below the reference “prime rate” at which commercial banks lend to their customers with the lowest default risk (currently 3.25 percent). It allows the Postal Bank a spread of only 0.03% (versus 3.2% for prime-rate loans) on what are subprime loans. The reported default rates on small-dollar loans in the “payday loan” industry are quite high compared to other loans: 4.8–6.4% on two-week loans in a sample of six states, 20% on six-month loans in Colorado, 53% on payday installment loans in Texas. Charging a risk-free rate on such loans would generate financial losses and thus require a subsidy from taxpayers. Peter Conti-Brown identified this problem in his critical evaluation of Senator Gillibrand’s 2018 bill, and rightly cautioned: “Let’s be clear: Keeping interest rates low for populations that have a high risk of default is a governmental subsidy.”

Such a subsidy would be inconsistent with Senator Gillibrand’s recent promise that postal banking would contribute to “shoring up the Postal Service” financially. It would likewise be inconsistent with the hope that postal banking as envisioned by Gillibrand will be “basically cost-free to the taxpayer,” to quote postal banking’s leading academic advocate, law professor Mehrsa Baradaran.

Here is what Gillibrand and Sanders say about the postal loan rate ceiling in a recent essay on Medium making the case for their Act:

At postal banks, loans would use the one-month Treasury Rate, the interest rate at which many of the world’s largest financial institutions are lent money. It’s often as low as 2%. This legislation says that if that rate is good enough for Wall Street, it’s good enough for every American.

Two peculiarities of this statement leap out. First, the authors seem to be unaware that the one-month Treasury Rate is currently well below 2%, at 0.08%. Second, to declare that every American deserves to borrow at the low rate paid by the US Treasury or by the world’s largest financial institutions is to wish away the fact that payday borrowers as a group are more likely to default.

There is only one way that the US Postal Service could offer deposits paying the same rates with the same service fees as commercial banks, and use the funds to make loans charging much less than private institutions for equivalent risk, i.e. operate with a much smaller spread, without losing money. That would be for the USPS to intermediate deposits into loans at unit costs much lower than those of competing private firms. There is no evidence that it can do that and no reason to expect that it can. The USPS today loses money delivering mail and packages, despite its legal monopoly on first-class mail. The case for profitable postal banking is built on wishful thinking.

I’d like to make two additional points about misleading statements by advocates of postal banking.

(1) The demographics of payday lending have sometimes been mischaracterized. Multiple news accounts of Gillibrand’s 2018 proposal quote the following statement from the senator: “There is a huge racial justice issue. The average person who gets a payday loan is a 44-year-old African American single mom.” I cannot find any statement by Gillibrand giving her source for that statistic. The only source I know for payday borrower demographic data is a report by the Pew Charitable Trusts. According to the report (p. 35, Exhibit 14), however, while there are slightly more female than male payday borrowers (52 versus 48 percent of borrowers), there are roughly twice as many white as black payday borrowers (the borrowers are 55 percent white, 23 percent black, and 14 percent Hispanic). The average borrower is not a mom or dad (38 percent are parents, 62 percent non-parents). Only 24 percent of borrowers are classified as single, although if we add in separated/divorced and widowed, we get to 53 percent. The claimed age figure is also off. In the Pew data, the average person who gets a payday loan is actually a 39-year-old white female non-parent.

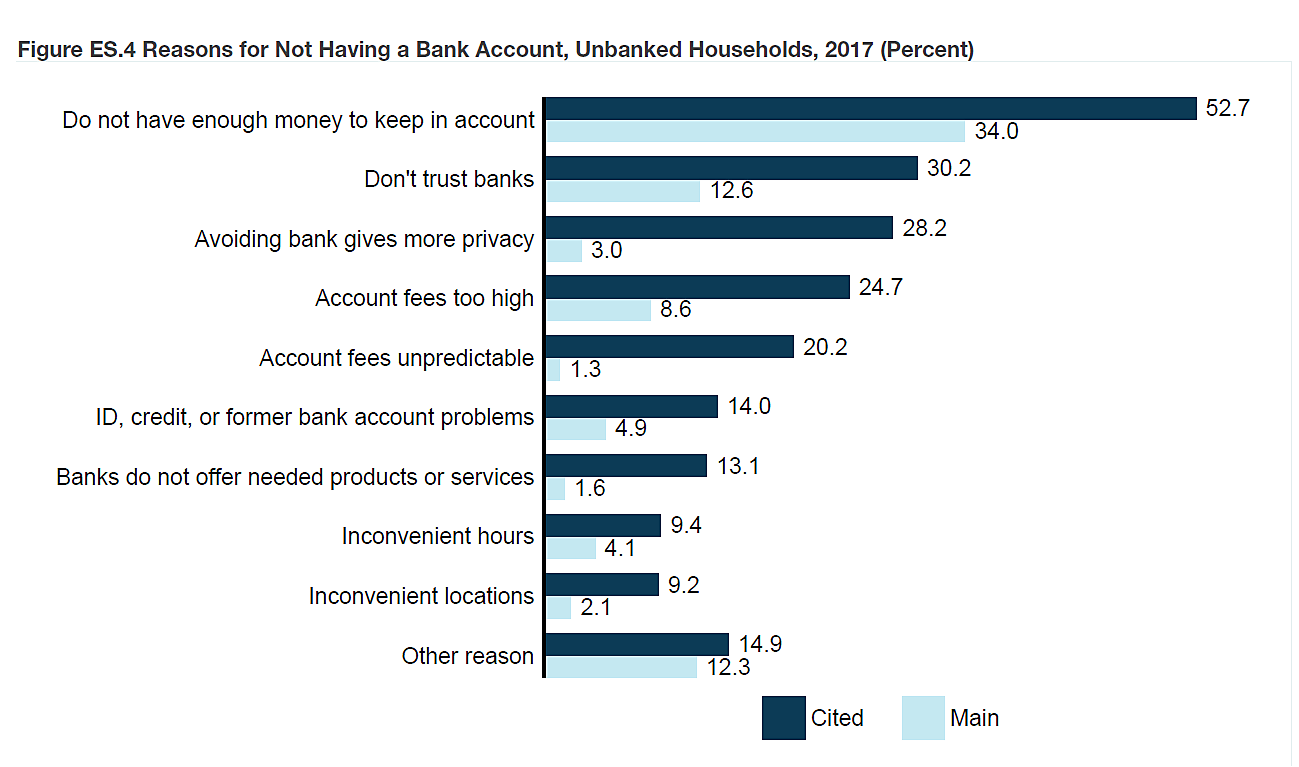

(2) The unbanked have sometimes been described as people who “don’t have access to bank accounts.” For example, one commentator writes that “an estimated 7 percent of American households don’t have access to bank accounts, according to the most recent survey from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.” But when you consult the FDIC report, it doesn’t say that. It says rather that 6.5 percent of households don’t have bank accounts. (That number is declining: in 2011 it was 8.2 percent.) It is misleading to call all reasons for not having accounts “lack of access.” At least some of those households, possibly most, have as much access to banks as the banked. They don’t live farther from a bank branch than their banked neighbors, and don’t lack the identity documents required by “know your customer” regulations. They choose not to open accounts.[2] The FDIC report surveys unbanked households, and finds that they cite many reasons for not opening bank accounts, at least half of which are not about anything reasonably called “lack of access.” Namely, “Do not have enough money to keep in account” (34% gave this as their main reason), “Don’t trust banks” (12.6%), “Avoiding bank gives more privacy” (3.0%), “Banks do not offer needed products or services” (1.6%). Here is the report’s bar chart of the reasons given:

Although postal banking advocates sometimes emphasize the problem of people living in “banking deserts,” it is noteworthy that only 9.2 percent cited “inconvenient locations” as a reason for not having a bank account, and only 2.1 percent called it their main reason.

Finally, to be skeptical of postal banking proposals is not to be enamored of the status quo. As suggested earlier, economists will ask: If there are profit opportunities in small-dollar lending, given the high prices charged by payday lenders, why aren’t mainstream banks and thrift institutions taking them? But the status quo in payday lending is not presumptively efficient given the heavy legal restrictions in place. Bank regulations stand in the way of competition from low-cost providers that would drive down prices. For a prominent example, regulatory barriers have blocked the retail giant Walmart from offering a full range of banking and financial services. Walmart applied for a license as an Industrial Loan Company in 2006. In response, as The American Banker has recalled, “State legislatures passed laws to block a future Walmart bank from opening branches, while lawmakers in Washington sought legislation to prohibit new ILCs owned by commercial companies.” Walmart shelved its plans. More recently the Transportation Alliance Bank, a Utah ILC, has been blocked from opening “branches at truck stops across the country” to serve interstate truck drivers, by states threatening to ban ILC branching.

Walmart stores today charge much less to cash checks than storefront check-cashing services. In 2018 Walmart began offering a phone-app-based alternative to payday loans to its own employees, partnering with the fintech firm PayActiv. (Hundreds of smaller firms have also signed up with PayActiv.) A worker with the app can have up to half of their next paycheck, for hours of work already performed, immediately transferred into their bank account for a $5 fee. If a branched Walmart-affiliated ILC or bank were allowed to offer payday loans to employees of other firms, that could greatly improve payday loan options for consumers without putting taxpayers on the hook.

************

[1] Postal Savings figures from Inspector General white paper (2014, p. 23); total bank deposits figures from Anderson (2003), Table 3, column 3.4 for 1947 and Table 5, column 5.8 (M2) minus Table 2, column 2.4 (currency in circulation) for 1964.

[2] A well-known piece of folk wisdom reminds us that a horse may choose not to drink despite access to water.